America’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Runs Through Ukraine

Luis Simón | 19 December 2022

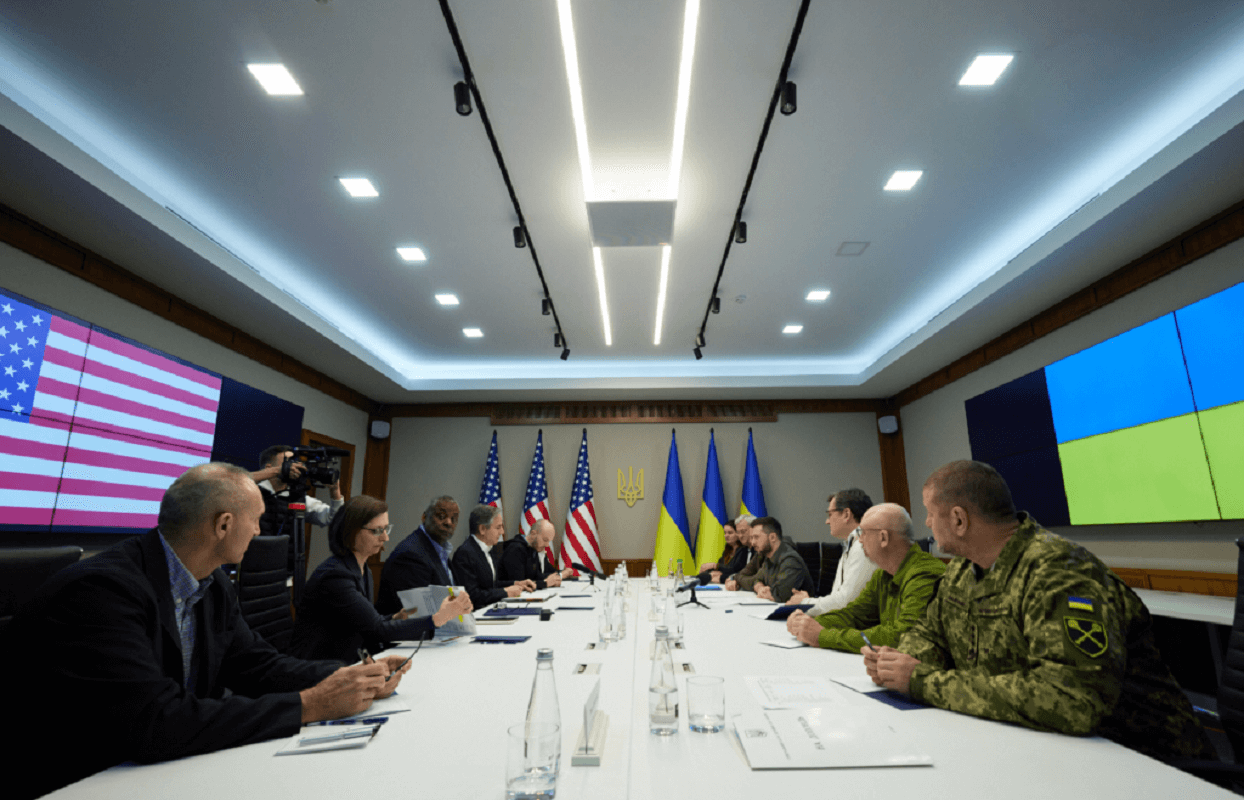

Over the past year, Washington has helped rally Europe to support Ukraine’s heroic defense of its sovereignty. Yet amidst the enthusiasm that this has generated, some observers remain concerned that the war in Europe will distract the United States from the more profound threat that it faces from China. They shouldn’t be. Given the deepening interdependence between Europe and the Indo-Pacific, and the growing cooperation between Moscow and Beijing, decisively defeating Russia remains the best way for the United States to successfully compete against China.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin recently argued that the United States “wanted to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine”. If the United States managed to achieve this, it could neutralize the existence of a threat to the European balance of power for the foreseeable future. And that could set the foundations for redirecting the bulk of U.S. strategic attention towards the threat posed by China in the Indo-Pacific. In contrast, abandoning Ukraine to its own luck could lead to the unraveling of the European security order. That would end up demanding a considerably higher share of America’s strategic bandwidth down the line, and thus constitute a far more serious drag on a much-needed rebalance to the Indo-Pacific.

Tackling Trade-Offs

Properly understanding the relationship between U.S. strategy in Europe and in the Indo-Pacific begins with recognizing three crucial facts. First, the security architecture in both regions is built on U.S. military power. Second, the United States devotes a higher share of its defense resources to these two regions than anywhere else. Third, the United States now faces great-power challenges in Europe and the Indo-Pacific simultaneously.

The existence of strategic tradeoffs between Europe and the Indo-Pacific is very real. What the United States does in one region impinges on its ability to resource deterrence in the other region. Thus, an over-prioritization of one region — and de-prioritization of the other — can open windows for opportunistic aggression. Indeed, the U.S. National Defense Strategy argues that China and Russia have expanded their cooperation and “either state could seek to create dilemmas globally for the Joint Force in the event of U.S. engagement in a crisis or a conflict with the other.” In this vein, some experts have warned about the challenge of dealing with simultaneous wars in Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

The importance of Europe and the Indo-Pacific above all other regions is typically justified on the basis that they are the only two regions that harbor the demographic, industrial, technological, and military potential to allow any power dominating them to seriously challenge and ultimately threaten the United States. Hence, it is important to simultaneously preserve favorable balances in Europe and Asia by ensuring that no single power or coalition of powers controls the resources of either region. The assumption that the balance of power in both regions is structurally delicate — and requires permanent U.S. engagement — has led to recurring concerns about over-prioritizing one region at the expense of the other.

But to what extent does that assumption hold today? In other words, how fragile are the regional balances in Europe and East Asia? The relative importance of each region has varied over time, and so has their degree of strategic interdependence. There is broad agreement that Europe was the center of gravity for Washington during the Cold War. While the Soviet Union did not match U.S. and European economic power, and may have faced structural economic challenges, it enjoyed significant levels of economic growth throughout much of the Cold War and remained an industrial and technological superpower. Moreover, communism enjoyed significant social appeal across Western Europe. Critically, Soviet military strength — nuclear and conventional — and presence across Central Europe posed an acute and persistent threat to the European balance of power. No equivalent threat existed in Asia. China was economically weak and inward-looking, and it was actually the Soviet Union that was considered the main regional threat to U.S. allies and interests in East Asia.

Today the situation has been reversed. It would be premature to draw too many lessons from Russia’s military performance in Ukraine and count Moscow out as a significant power — Russia still poses an acute threat to Europe and the United States given its large nuclear arsenal and ongoing modernization efforts. However, Moscow’s inability to hold on to its early gains in eastern and southern Ukraine and its high rate of equipment loss raise questions about its ability to pose a conventional military threat to NATO. Such problems are further compounded by Russia’s growing economic and political isolation in Europe. Critically, NATO enjoys significant geostrategic depth, with enlargement having pushed the alliance’s defense perimeter across the northern European plain and well into the Baltic and Black Seas. Finland and Sweden will now add further depth — and capability — to NATO.

Other than Russia, there are no serious challenges to the European balance of power. Leaving aside the question of whether greater European strategic autonomy or sovereignty may be beneficial to the United States, Europe remains hampered by diverging national interests and its autonomy largely limited to economic affairs. If anything, the war in Ukraine may have increased Europe’s security and energy dependence on the United States.

Even if Europe must still grapple with a number of economic and security woes, the fundamental European balance of power is not in question. The same cannot be said of the Indo-Pacific, where a rising China poses a formidable, cross-domain threat. Its military modernization and assertiveness have improved China’s regional military position vis-à-vis the United States, and challenged America’s free movement within the Western Pacific theater of operations. The fact that China’s territory hugs much of the Western Pacific and that the U.S.-led defense perimeter in East Asia has limited geostrategic depth puts Beijing in a position to project its power into the high seas. Moreover, many countries in East Asia are part of China’s economic orbit, and maintain good political relations with Beijing.

The United States does in fact recognize the growing disparity between Russia and China. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks recently alluded to Russia as an “acute threat,” meaning “it can be sharp, near term and potentially more transitory.” China, by contrast, is seen a “pacing challenge” that can “bring a comprehensive suite of power” to bear. This distinction is not minor. Moscow still represents a formidable nuclear threat and may be able to threaten U.S. allies in Eastern Europe. But it is not in a position to upset the European balance of power, let alone the global one. China is. In short, the United States faces a balance-of-power challenge in the Indo-Pacific, and a stability problem in Europe. This puts the Indo-Pacific on a higher level strategically.

Arguably, the degree of interdependence between Europe and the Indo-Pacific is greater today than during the Cold War. Back then, if the United States felt it had to step up its contribution to Europe in response to a perceived increased Soviet threat there, the resulting risk elsewhere was less acute. After all, Soviet resources were also limited, and a Soviet prioritization of Europe would automatically limit Moscow’s own strategic bandwidth in East Asia. The sense of geostrategic tradeoffs between both regions and sets of U.S. allies was therefore not as salient as it is today.

Appropriate Priorities

The rise of China means that the current challenge is more closely akin to World War II, when the United States and its allies faced simultaneous challenges from different competitors in different theaters. Fortunately, today the European balance does not appear to be in danger. Having said that, the prospect for endemic instability in Eastern Europe, the ongoing risk to U.S. treaty allies, Russia’s nuclear status, and Washington’s existing commitments suggest that the level of U.S. engagement in Europe may be greater than balance-of-power considerations alone would require. Thus, the region will remain more important to Washington than any other besides the Indo-Pacific. Yet this importance will likely diminish.

At this juncture, it would be a mistake to pivot to China with the expectation that European states can preserve deterrence and security on the continent with limited U.S. engagement. The war in Ukraine demonstrates that U.S. political and military leadership remains the center of gravity for any effort to uphold the European security architecture. Put bluntly, it is difficult to explain Russia’s failures in Ukraine without reference to U.S. support for Kyiv. An overly hasty pivot that led to the collapse of Europe’s security architecture would end up demanding far more strategic resources and attention down the line.

Any viable strategy to keep Russia in check will require a sustained U.S. engagement in Europe, especially if we assume Russia will ultimately re-arm and rebuild. However, a Ukrainian victory will enable this engagement to increasingly focus on factors like command and control, fires, and key enablers, which would complement a much-needed build-up in Europe’s own defense capabilities and a stronger European role within NATO. This would then pave the way for the United States to shift forces from Europe to the Indo-Pacific in the event of a crisis in Taiwan or elsewhere. Contrary to what others have argued, dealing with the Russian threat decisively, and significantly degrading Russian power, may actually be the best way to ensure a sustainable U.S. rebalance to the Indo-Pacific. This is not only in Europe’s or America’s interest — U.S. Indo-Pacific allies have a strategic stake in Washington’s success in Europe too.

Luis Simón is director of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy at the Brussels School of Governance, and director of the Brussels office of the Elcano Royal Institute.

This article was originally published on War on The Rocks.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.