The G20 and multilateralism after Trump

Glen S. Fukushima | 28 November 2020

The 2020 Riyadh Summit, the 15th meeting of the Group of 20, was hosted by Saudi Arabia on Nov. 21 and 22. Expectations for this year’s meeting were not high, for three reasons.

First, the coronavirus pandemic had forced the meeting to be held virtually, so the participants were unable to engage in face-to-face meetings or in the bilateral discussions that in the past have often produced more concrete results than the summit communiques that necessarily reflected the lowest common denominator of the 19 countries and the European Union, which comprise the G20.

Second, Saudi Arabia, this year’s host country, continues to be criticized for its human rights policy. In particular, the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istabul in October 2018, which led to widespread protest against the Saudi government and calls for many of the European heads of state to boycott the summit.

Third, the United States, one of the creators of the G20 in 1999, had since the inauguration of President Donald Trump in 2017 taken policies counter to most of the other members on such issues as trade, climate change, refugees and immigration. In addition, Trump’s loss in the U.S. presidential election of Nov. 3 meant that the U.S. was represented by a lame duck president scheduled to leave office on Jan. 20, 2021 — although he reportedly said to his counterparts: “It’s been a great honor to work with you, and I look forward to working with you again for a long time.”

Future of multilateralism

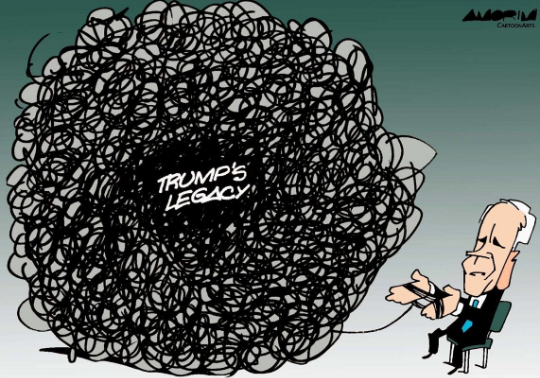

The G20 is just one of many multilateral organizations, institutions, and initiatives that have suffered over the past four years because of the Trump administration’s policy of “America First,” which embraces unilateralism and bilateralism while rejecting multilateralism. But with the election of former Vice President Joe Biden and with Tony Blinken as the new secretary of state, the U.S. is expected to re-engage with multilateral organizations and institutions and to reinvigorate ties with its allies and partners.

Nowhere is this expectation higher than in Europe. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas argued in a Nov. 16 Washington Post op-ed piece titled “Joe Biden Can Make Trans-Atlantic Unity Possible” that “Europe and America need a transatlantic ‘New Deal’ to adapt our partnership to global upheavals and in line with the depth of our bonds, common values and shared interests … what is at stake … is our ability to preserve our way of life and to pursue our never-ending quest for individual freedom and collective progress. There won’t be any better, closer and more natural partners for this than America and Europe.”

Four days later, on Nov. 20, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen gave a major address to the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations, which she opened by praising President-elect Biden as a “committed trans-Atlanticist” and expressing satisfaction that “we now have a friend in the White House.”

President von der Leyen proposed that the U.S. and Europe forge a “new global alliance” focused on four areas: (1) overcoming the global pandemic, including the development and distribution of vaccines; (2) protecting the climate and the environment based on the European Green Deal; (3) governing the digital economy and technology, including “human-centric artificial intelligence,” and jointly writing the global rules to protect shared values and democracy; and (4) upholding and upgrading international institutions and governance, including reforming the global trading system to deal with China as an “economic competitor and systemic rival.”

The European Commission president reiterated that the four areas she cited were merely the “core” of a “renewed trans-Atlantic agenda,” and that many other issues are ripe for mutual cooperation between the U.S. and Europe.

On Nov. 23, former Mexican Foreign Minister Jorge G. Castaneda published an op-ed piece in the Washington Post titled “Biden Can Inspire Latin America.” He wrote: “Mr. Biden inspires Latin America by advocating the values the United States should stand for: human rights, democracy, fighting corruption, managing climate change … he can inspire Latin Americans who have always embraced multilateralism by returning to multilateralism whether it be to institutions or to values.”

And Japan?

In the short span of one week, we have seen the foreign ministers of Germany and France, the president of the European Commission, and a former foreign minister of Mexico publicly expressing their welcome, stating their expectations, and offering their proposals for their respective country or region to work with the new Biden administration.

Japan, as the world’s third largest economy and America’s closest security ally in Asia, surely has something to contribute to this discussion. Perhaps it would take the form of a set of proposals for the U.S. and Japan to work together to address regional and global issues. Or a set of joint initiatives for Japan and South Korea to work with the U.S. on regional or global issues. Or a set of proposals for Japan, Australia, and India to cooperate with the U.S. in the context of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” framework.

Whatever the specific contents of the proposals, clearly conveying Japan’s (and Asia’s) hopes, expectations and proposals to the Biden administration and to America can help to ensure that the new administration will devote the necessary time, attention and resources to Asia—as it will to Europe and Latin America—that the important region so richly deserves.

Glen S. Fukushima is a writer based in Washington, D.C. He has served as Deputy Assistant United States Trade Representative for Japan and China at USTR and as President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan.

This article was originally published on The Japan Times.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.