Bangladesh: 50+ Years Later, Is the ‘Muktiyuddha Chetana’ on the Verge of Losing Its Relevance?

Soham Das | 02 August 2024

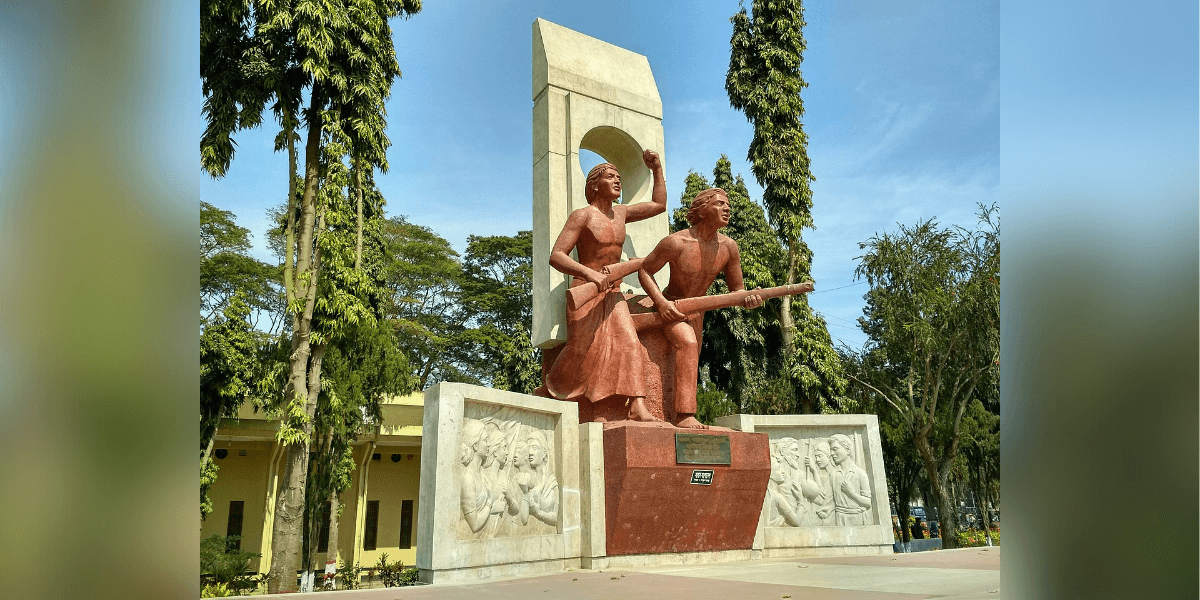

In the name of the Awami League's so-called manifesto of the ‘Muktiyuddha Chetana’ (Liberation War spirit), large-scale corruption, looting and misdeeds have been carried out during Sheikh Hasina’s premiership.

The unity of students across Bangladesh in fighting against corruption and autocracy; a violent government crackdown causing bloodshed and the killing of protestors at a staggering rate; one Abu Sayed becoming the new generation’s ‘face of self-sacrifice’; a nationwide curfew and blockade of the internet; and a Supreme Court decision that eventually scaled back the conflict – this July in Bangladesh has witnessed one of the most significant mass uprisings of recent times.

When it started with peaceful protests in university campuses, few would have imagined the storm would last as long as it has.

In the wake of unscrupulous state brutality against protestors and Sheikh Hasina labelling the protestors ‘the grandchildren of razakars’ (it is a popular tactic of fascist political parties to mark the opposition as some historically blemished ‘other’ – pretty similar to the BJP’s labelling of the Indian opposition as ‘anti-national’), progressive intellectuals from the state of West Bengal, though in a very small number and among whom were mostly students, human rights activists, journalists and several authors, came forward and expressed their solidarity in support of the movement.

On 19 July, several leftist students’ unions and human rights organisations organised a protest march in Kolkata. On their way to the Bangladesh deputy high commission, a clash ensued between them and the city police, following which many of them were detained at the police headquarters at Lalbazar.

Social media activities such as the sharing of news from ground zero, the use of harsh words for the repressive measures of Sheikh Hasina’s government, and mourning over the unfortunate deaths of young students are also in full swing, quite naturally. Many people from my circle of friends and acquaintances have mentioned the role the intelligentsia of the two Bengali-speaking regions played at the time of the 1969 mass uprising as well as the 1971 Liberation War.

For instance, when 15-year-old Tahmid Tanim, a ninth grade student, was killed after being hit by rubber bullets on July 18 in central Bangladesh’s Narsingdi, journalist Arka Bhaduri posted a poem by eminent poet Al Mahmud penned in the memory of two student-martyrs of the 1969 uprising, Amanullah Asaduzzaman (known as only ‘Asad’) and Matiur Rahman Malik (16 years old at the time of his killing).

Another journalist and prose writer, Priyak Mitra, quoted a passage from Ekushey Padak awardee and novelist Akhtaruzzaman Elias’s epic period piece ‘Chilekothar Sepai’ (‘The Soldier in an Attic’) while criticising popular science-fiction author Muhammad Jafar Iqbal for his anti-student comments on the ‘Razakar controversy’, sparked by the honourable prime minister herself.

Tanmoy Bhattacharjee, a poet and researcher, recently wrote an interesting article about a pro-Bangladesh leaflet authored and published by Subimal Basak (a prominent face of the 1960s anti-establishment Bengali literary movement ‘Hungry Generation’) just before the start of the war in early 1971.

Senior journalist and documentary-maker Soumitra Dastidar, who is also an expert on socialist politician Maulana Bhashani, posted on July 15 the story of a follower of Bhashani to highlight the fact that the Liberation War was actually a mass struggle.

Some independent journalists have even criticised the ignorance shown by the current mainstream media of West Bengal, recalling how newspapers and radio had played their part at the time of the crisis – for instance, Akashvani newsreaders Debdulal Bandyopadhyay and Nilima Sanyal became almost household names at the time.

While there are many other types of posts, as mentioned already, these few, on the whole, depict the emotional attachment still felt by so many Bengalis in connection with the war.

Interestingly, all these are in support of a movement organised against the reinstatement of a 30% public sector quota for the children and grandchildren of Liberation War veterans.

To be very frank, the events that led to the war, and indeed the war itself, had a great impact on South Asian politics. The Indian state machinery provided wholehearted assistance and aid to the war effort. But more striking was the overwhelming participation of ordinary people, government officials and public figures.

West Bengal, being socially and culturally connected to its eastern neighbour, was on the forefront of displaying solidarity with the war effort. Calcutta not only became the capital-in-exile of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh but also gave shelter to a huge number of middle class refugees.

Besides political support, civil society efforts like the ‘Council for Promotion of Communal Harmony’, which was founded by progressive intellectuals in Calcutta, and religious organisations like ‘Missionaries of Charity’ and the ‘Ramakrishna Mission’, were actively involved in refugee rehabilitation and relief.

The involvement of the popular intelligentsia was spontaneous, and the ‘Black Night of March 25’ (the day on which the Pakistani army and local collaborators executed Bengali professors, journalists and physicians) added fuel to the fire.

Filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, famously known for films made on the 1947 partition and the post-partition crisis, made a documentary entitled ‘Durbar Gati Padma’ (‘There Flows the Padma, the Mother River’), which IMDb describes as portraying “the determination of the common man of Bangladesh to stand up to tyranny”. Leading newspapers regularly published political cartoons by famous cartoonists in support of the cause for an independent Bangladesh.

In a nutshell, the Bangladesh Liberation War was not restricted to the political freedom struggle of a specific geographic region, but became a struggle for socio-cultural existence.

However, no matter how many people still feel about it, the realities of the time of the liberation struggle are now long gone – while the Awami League (AL) led the struggle then, it is the one orchestrating fascist rule in Bangladesh today. So it is simply unjust to use the sentiment of the war to justify its dictatorial regime.

In Bangladesh, the science fiction author Iqbal faced backlash from university student unions for his stand against students who responded to Hasina’s comments by shouting the slogan: “Who are you? Who am I? Razakar, razakar. Who said that? Who said that? Dictator, dictator!”

However, students found support among other celebrities like actors Ziaul Faruq Apurba and Mehazabien Chowdhury and singer-songwriter Farzana Wahid Shayan. In West Bengal, even though several artistes like author Amar Mitra, actress Swastika Mukherjee, singer Sahana Bajpaie, music director Indraadip Dasgupta and others had voiced their protest to the best of their capacities, the popular faces for the large part remained silent on the incident. Even the miserable deaths of teenagers were not enough for them (who also include some so-called progressives) to speak up.

This may be attributed to the complexity of Bangladesh’s current political mayhem and the strained nature of the relationship between the two countries. But at the same time, one has to admit that this ‘act of cowardice’ has become the ground reality, with the role of West Bengal’s public intellectuals in shaping public opinion having turned into a joke in recent years.

Global politics has completely changed in these five decades. A belittling ‘big brother’-type attitude on our part over the years only deteriorated the mutual admiration Bangladeshi people once had for their closest neighbours.

The ‘India Out’ sentiment, which has grown in the past decade in Bangladesh, gained momentum following allegations about Indian interference in the last general election. India is no longer seen as a friend, with thousands having celebrated the Indian cricket team’s defeat to Australia in the last World Cup final.

On the other hand, the Hasina-led AL, which is thought to be close to the Modi-led BJP government and has been in power for more than fifteen years now, has always used the 1971 war for the sake of its own interests. In the name of its so-called manifesto of ‘Muktiyuddha Chetana’ (Liberation War spirit), large-scale corruption, looting and misdeeds have been carried out during Hasina’s premiership.

Rigged elections, the imposition of state terror on the opposition, and the opposition boycotting elections – these have become common in ‘sonar Bangla’ (‘Golden Bengal’, as the region was once termed because of its rich cultivation). As Salman Siddiqui, the president of the Socialist Students’ Front has pointed out, the AL’s governance is the complete opposite to what the Liberation War was truly fought for – equity, human dignity and social justice.

Even though the central leadership was in the hands of the AL and the indomitable spirit of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (father of Sheikh Hasina and former leader of the AL, popularly known as ‘Bangabandhu’, or ‘friend of Bengal’) had indeed acted as a great source of motivation for the nation’s struggle against Pakistani oppression, the AL was not the only party to be at war with the enemy. The role played by leftist parties has often been deliberately omitted.

In fact, it was Maulana Bhasani who first protested against the central authorities of East Pakistan and advocated for autonomy in 1948. During the Liberation War, several leftist parties took part in the fighting, both inside and outside East Bengal, despite stiff hostility from the others associated with the war.

Thus, the Liberation War cannot be the property of one party; rather, it was a people’s war in the true sense, where several parties, in spite of their ideological differences, fought together against a common enemy.

Out of the just-scrapped 56% reservation for specially entitled classes in public sectors, 30% was allotted to the descendants of freedom fighters. Not only did many people avail the quota by faking their identity, but the AL has also been repeatedly alleged to have distributed the quotas exclusively among its own people.`

This has only resulted in unemployment. According to an ILO report, the number of unemployed persons in Bangladesh was more than 3.6 million in 2021, which corresponded to an unemployment rate of 5.2%. The rate of unemployment among the youth was alarmingly high, at 14.7%.

There was a nationwide protest against the freedom fighter quota in 2018, too. Under severe pressure, the Hasina government was forced to announce the abolishment of all quotas, and it did introduce reforms when the protest resumed after three months of government inaction.

This time, the movement achieved a much bigger shape as the demand is to end the overall corruption that has intoxicated the whole system. Moreover, the protestors have also been agitating against the Chhatra League (the AL’s student wing), which has repeatedly violated human rights in academic spaces. Even though the AL government has played its old game of projecting the movement as a conspiracy orchestrated by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, its main political opposition, this did not have much of an effect on the spontaneity of the movement.

In the face of the current situation, perhaps that day is not too far when the Liberation War itself will lose its relevance to the upcoming generations. If that really happens, it will not only be an insult to those thousands of souls who made the supreme sacrifice, but also be an unfortunate effacing of history, and the ruling party and its ‘opium of nationalism’ will have to take the lion’s share of the blame.

Soham Das is a Kolkata-based independent researcher and bilingual author who takes special interest in history, politics and culture.

This article was originally published on The Wire.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.