India’s ‘Sheikh Hasina Problem’ is Not Going Away Easily

Ahmede Hussain | 25 August 2024

Letting Hasina stay in India for an indefinite period can indeed strain its relationship with Bangladesh further.

For one and a half decades, India unabashedly supported Sheikh Hasina’s brutal and dictatorial regime. The 20-day-long violent uprising that forced her to flee to India in a military cargo plane, witnessed the death of 542 people in 20 days. Year after year, South Block turned a blind eye to Hasina’s kleptocratic government that helped its cronies syphon an estimated $150 billion out of the country. The amount is double the size of Bangladesh’s national budget.

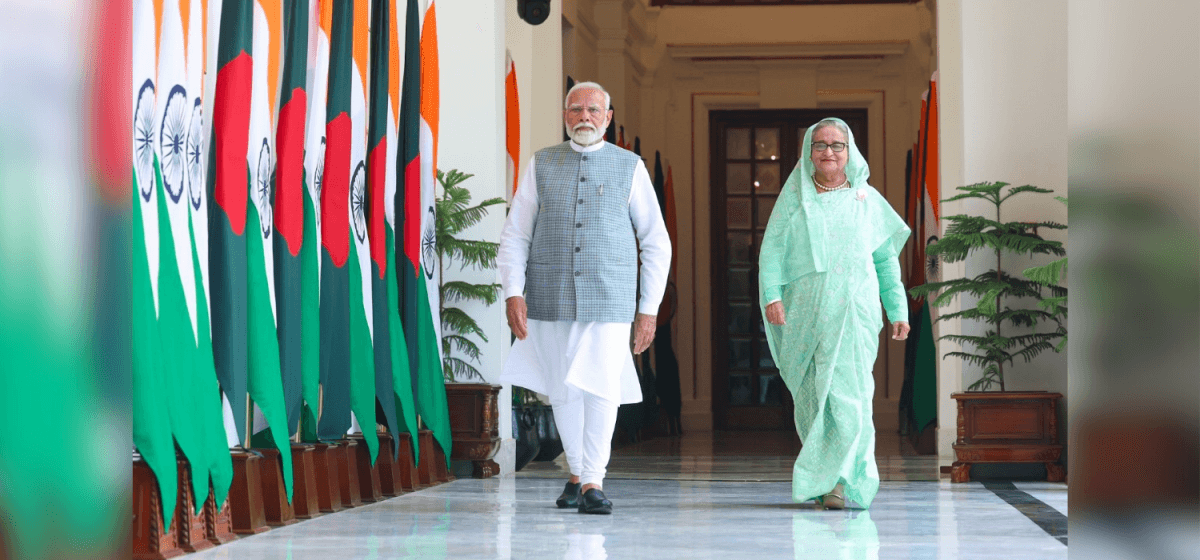

India refused to hedge its bets in Bangladesh even after repeated requests, especially over the past several years. During Hasina’s rule, the Narendra Modi government never tried to make friends with Bangladesh or its people; rather it was ready to risk India’s goodwill and enlightened national interest for the sake of Hasina and the Awami League. When the United States tried to punish human rights violators in Bangladesh, Indian lobbied withWashington so that the US gave Hasina some breathing space— Delhi told the US that it “…can’t take us (India) as a strategic partner unless we (India and the US) have some kind of strategic consensus.”

On July 19, the day 75 people died mostly in police fire, Dr S Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister of the world’s largest democracy, called it“Bangladesh’s internal matter”. The day after Hasina’s fall in a mass upsurge that Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus called Bangladesh’s Second Independence, Jaishankar, in his speech to parliament, failed to see why the people of India’s next doorneighbour had risen in unison against India’s closest ally in South Asia.

Instead of soul searching, some in the Indian media found the usual suspects behind Hasina’s fall— Pakistan, China and the US. It is indeed ironic that China and the US, both rivals in the formation of Cold War 2.0 in the Pacific, are seen as an ally in tiny Bangladesh. The involvement of Pakistan is also ludicrous. Last December Bangladesh edged past both Pakistan and India in per capita GDP, and the country’s median age is 26. Members of the Gen Z who spearheaded Hasina’s ouster don’t have 1971 and the Independence War in their collective memory— India and Pakistan, to them, are just two countries, about whom an array of memes are usually made.

Some in the Indian media even exaggerated the scale of attacks on Hindus in post-Awami League Bangladesh to serve their own agenda. Coverage like this trivialises the bigger issue of the oppression of the minorities in the sub-continent as a whole.

Like its media, the Indian establishment is also failing to see why keeping Hasina in Delhi is a burden. The deposed dictator faces a slew of charges. According to Unicef 32 children were killed in the protests: the youngest child killed had yet to turn five. Of them, Riya Gop, whose parents were Hindu, was shot in the head by a stray bullet while she was playing on a rooftop. It is impossible to defend and give shelter to a person whose command responsibility in these inhuman acts is undeniable.

As it is, India’s relationship with Bangladesh doesn’t look good. Thanks to its years of support for Hasina, ordinary Bangladeshis are finding it difficult to separate India from the Awami League; hours after Hasina’s fall, the Indira Gandhi Cultural Centre in downtown Dhaka was torched. Only last week, the Indian visa application centre in Dhaka resumed limited operations.

Letting Hasina stay in India for an indefinite period can indeed strain its relationship with Bangladesh further. When charges of crimes against humanity against Hasina are finalised, the new Bangladesh government can seek her extradition. India and Bangladesh have an extradition treaty, under whose provisions Bangladesh may want her back to face a slew of cases she’s facing, of which 27 are for murder. To make matters worse, Bangladesh government has revoked Hasina’s passport, the one she used while fleeing to India, making her stay in Delhi more complicated.

Then there is the risk of alienating Bangladesh’s youth by harbouring her in India and pushing hundreds and thousands of young Bangladeshis towards China. This is a mess that evidently India’s inefficient and lethargic bureaucracy has brought upon itself.

One big step towards solving a problem is accepting the fact that there’s a problem. It’s high time India engages with the people of Bangladesh and stops ‘leasing it out’ to its old chums. South Block has to find new friends in Bangladesh, and it has to realise that its old policy has failed and its old friends in Bangladesh are despised by the public.

The country also needs to change the way it sees Bangladesh. India’s help during Bangladesh’s independence war is a part of our shared history. But the help given 54 years ago isn’t enough to make Bangladesh feel indebted forerer. The US liberated half of Europe, but the EU isn’t the US’s colony, neither does Washington try to throttle democracy in France or Italy or Germany. If India wants to become a regional superpower, its foreign policy actors have to work like one.

Ordinary Bangladeshis aren’t India’s enemy. The problem is the Indian establishment.

Ahmede Hussain is a Bangladeshi writer and journalist. He’s the editor of the anthology ‘The New Anthem: the Subcontinent in its own Words’ (Tranquebar; Delhi).

This article was originally published on The Wire.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.