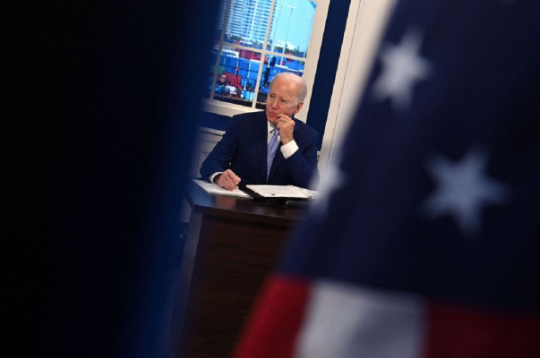

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Biden’s First Year

Jack Detsch | 03 January 2022

Biden wants a new normal, but Trump’s shadow looms large.

It’s probably not wise to sketch out a “Biden doctrine” after just one year, but if you want to try, start at the top. U.S. President Joe Biden was inaugurated on the steps of a fenced-off U.S. Capitol on Jan. 20, just two weeks after a pro-Trump mob ransacked Congress.

It’s a scene that’s largely defined Biden’s first year as president: trying to find a new normal in U.S. foreign policy with a country still riven by the pandemic and deep-seated political polarization. And if the fledgling administration sought to return to the international rules of the road former U.S. President Donald Trump trod upon, Biden is staring down challenges by China, which has plans to be the world’s No. 1 superpower, and a resurgent Russia, which spent 2021 dialing up military pressure in Ukraine.

Even though allies and partners are now the foreign-policy tool du jour, there’s an important area of continuity between Biden and the former commander in chief he once told to “shut up” on the debate stage. Biden has put together a retrenchment-minded foreign policy that has seen U.S. troops pull out of Afghanistan after two decades of war. The United States will instead husband its economic strength at home to fight terrorism from “over the horizon.”

Is that going to be enough? Biden’s detractors insist it’s not and worry the United States is losing credibility on the world stage with a haphazard and deadly withdrawal from Afghanistan that drew comparisons to the fall of Saigon. Here’s the good, the bad, and the ugly after Biden’s first year in office.

The Good

Friends in new places: Biden came into office with a serious foreign-policy conundrum that also befell his one-time boss, former U.S. President Barack Obama, as well as Trump: Big alliances like the 30-nation NATO—or even the 10-country Association of Southeast Asian Nations—were too slow and ponderous to keep up with Russia and China’s sudden moves on the global stage. So the Biden team has opted to thread the needle. Washington has used the four-nation Quadrilateral Security Dialogue that includes Australia, India, and Japan as an engine for security and vaccine distribution in the Indo-Pacific and the newly constituted AUKUS bloc with Australia and the United Kingdom to provide Canberra with nuclear-powered submarines.

China’s saber-rattling has helped the United States lock in some of these new mini-lateral groupings. The kerfuffle over Whitsun Reef, where the Chinese moored civilian-flagged fishing boats in disputed waters, helped end the honeymoon between outgoing Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Chinese President Xi Jinping, forcing Manila back into the longer-term security deal with Washington it had sought to shed. And the decadeslong courtship between Washington and New Delhi looks like it’s moving toward something more serious as China continues to build up forces near its disputed territory with India.

But it’s not just limited to the Indo-Pacific. As Russia amasses more than 100,000 troops on its border with Ukraine, the Biden administration frequently engages the so-called Bucharest Nine, former nations of the Soviet Union, including Poland and Romania (where the United States stations missile defenses)—even pledging to add more troops to NATO’s eastern flank if Russia invades Ukraine again.

Bring the boys (and girls) back home. Almost everybody acknowledges that Biden’s management of Trump’s decision to pull out of Afghanistan was chaotic and the Taliban’s return to power just days before U.S. troops left caught the administration flat-footed. But the president has still touted the withdrawal as a signature accomplishment, with this Christmas being the first in 20 years that U.S. boots weren’t in Afghanistan. The war on terror isn’t over: U.S. troops are still on the ground in places like Iraq and Syria, and drones are in the skies over Somalia. But the administration insists the United States has washed its hands of the regime-change foreign policy that characterized former U.S. President George W. Bush’s years and bedeviled the Obama team in Syria.

A senior administration official summed it up. Three administrations in a row set “quite grandiose goals in this most volatile region of the world,” the official said. It didn’t work in Iraq, and it didn’t work in Afghanistan. “We really just kind of concluded that, you know, setting these types of objectives, the ends totally outstrip the means.”

The Bad

What’s the plan, Stan? Yes, as U.S. officials are fond of telling reporters, the Biden administration is working with allies and partners on a great number of issues. But the Biden administration has, at certain points, found itself ground down by the careful, deliberate interagency process that was meant to shield the White House’s course from the foreign policy-by-tweet method of Trump’s tenure. At times, it broke down, with allies finding out about Biden’s timeline to withdraw from Afghanistan through media leaks, and the French briefly cutting off diplomatic relations with the United States over the AUKUS submarine deal.

For all the happy talk, behind closed doors, U.S. allies have déjà vu: They hear lip service and see the United States doing what it wants. And the process-driven administration has been locked in strategic reviews for much of the year, leaving many allies (and everyone else) on the outside looking in—and wondering if the United States really has a plan to deal with its biggest strategic challenges, such as China and Russia.

The Biden team has tried to stitch things up by rapidly declassifying intelligence to get on the same page as European allies in the Ukraine crisis, and there’s a push from the Defense Department to call out China and Russia’s bad behavior more publicly. But some fear the Biden administration’s year of reviews amounts to little more than busy work.

“No decisions, no changes, no sense of urgency, no creative thinking. Lots of word salad,” one congressional aide told Foreign Policy of the Pentagon’s recently completed review of U.S. troop deployments around the world.

What’s the deal? Biden came into office with a very narrow window to get a fresh Iran nuclear deal hammered out, fearing hard-liners would take over in Tehran and facing frustration from both Democrats and Republicans in Congress over not being clued in on the process. Hard-liners did take power in Tehran, Congress is still not thrilled about the prospect of a new nuclear deal, and Iran is making steady advances on uranium enrichment that have left some in the U.S. delegation fearing talks could be null and void.

“Either we reach a deal quickly or they slow down their program,” a senior U.S. official told Foreign Policy earlier this month. “If they do neither, [it’s] hard to see how [the] JCPOA survives past that period.”

It’s not all gloom and doom though. U.S. officials are hopeful that new channels of communication between Saudi Arabia and Iran, two longtime rivals, could help reduce the risk of miscalculation in the Middle East. And Iran-backed militias in Iraq have been mostly quiet for the past five months, giving the Biden administration some hope that high temperatures that characterized the months after Quds Force leader Qasem Soleimani’s death in a U.S. drone strike could finally cool down.

The Ugly

Bar exam. Russia’s military buildup in Ukraine was seen as Biden’s first foreign-policy test earlier this year. It’s now turned into the geopolitical equivalent of a bar exam, with Russian President Vladimir Putin again building up troops for the possibility of a renewed invasion that could charge deeper into the country.

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once defined Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” For Biden, the characterization has held true. U.S. officials are hopeful of returning Russia to the bargaining table for talks next month instead of escalating the situation.

In some parts of the administration, Russia is seen as an “ankle biter” type of problem, and there’s a desire to make it go away so Biden can focus on bigger things, such as China. But Moscow has proved a vexing near-term security threat—and not just in Ukraine. The Pentagon and the U.S. State Department have grappled with the U.S. National Security Council (NSC) for the better part of the year over whether to send more defensive lethal aid to Ukraine (like Javelin anti-tank missiles that could blunt a Russian armored assault). The NSC relented in September, but another package is awaiting signature on Biden’s desk.

Is it 2014 all over again? Sources familiar with the aid freeze said they were worried about the United States repeating the Obama-era mistake of trying to give Russia an off-ramp from the conflict.

Afghanistan’s bloody aftermath. Yes, Biden got U.S. troops out of Afghanistan, but it came at a cost. Some 13 U.S. troops died in August when an Islamic State suicide bomb ripped through a security checkpoint at Kabul’s airport. Now, Republicans in Congress—poised to win back one or both houses—insist the State Department is stonewalling their search for answers into what went wrong. And a harsh winter has left the Taliban mostly powerless to feed a malnourished country, with China and the United States facing (diplomatic) blows over a humanitarian aid exemption.

But even as Biden insists U.S. foreign policy is turning away from the war on terror, desperate scenes from Afghanistan have given some analysts, experts, and congressional aides pause. Is a strategy of striking terror targets from U.S. bases in the Middle East actually viable without intelligence assets on the ground? And does the U.S. withdrawal leave a power vacuum for China and Russia to exploit?

The withdrawal hasn’t left the Biden administration with a military dividend to pivot to the Indo-Pacific—at least, not as much as it was hoping. Although Biden has pledged to be an anti-Trump president, his economic playbook to counter Beijing through economic growth and continued tariffs looks eerily familiar. Efforts to move more U.S. troops to Asia have been undercut by internal politics in the region and bureaucratic churn back in Washington. And Biden’s push to make the United States a beacon for democratic values abroad—mostly through a virtual summit that included backsliding countries—is challenged politically at home by scores of Republicans who (still) haven’t accepted Trump’s election defeat. With all that in the rearview, year two for Biden will be a wild ride. Buckle up.

Jack Detsch is Foreign Policy’s Pentagon and national security reporter.

This article was originally published on Foreign Policy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.