In Bangladesh, A Government Without A Foreign Policy

Bangladesh’s ‘friendship to all, malice to none’ is not a policy

Anu Anwar | 25 March 2023

Bangladesh, a country of 170 million people, is sitting on the hotbed of the geo-strategic Bay of Bengal with an economy of US$470 billion, increasingly getting traction from great powers. In recent years, the country has made headlines for its economic success, more recently also for economic debacle.

But the most unprecedented attention it gets is due to Indo-Pacific geopolitical reconfiguration on the horizon of US-China strategic competition and its regional implications in South Asia, where Bangladesh sits within the firing range of three nuclear powers – China, India and Pakistan – and the volatile state of Myanmar. In any major flare-up in South Asia, regardless of Dhaka’s preference, Bangladesh will be affected one way or another.

While some observers argue that on the regional level, China and India are engaged in a tug-of-war for Bangladesh, others have pointed out that Bangladesh has been benefiting from the China-India rivalry. However, factual evidence suggests Bangladesh’s perceived benefit is more a byproduct of great-power competition than an outcome of Dhaka’s proactive strategies to hedge between them.

As a matter of fact, Bangladesh has no foreign policy. What is over-cited by Bangladeshi officials as foreign policy, in effect, doesn’t stand as a policy by any means.

“Friendship to all, malice to none,” a cliché that then-prime minister Sheikh Mujibar Rahman quipped in 1974 as a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), is just a rhetorical catchphrase.

This one-sentence statement doesn’t provide any policy goals, strategic planning, or modus operndi. At best, it can be counted as an unrealistic dictum that appears to echo Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s realistic dictum of “hide your strength, bide your time.”

China, up until Xi Jinping, largely observed this “hide-bide” dictum in its foreign and defense policies as the guiding principle, while Beijing produced white papers, policy memos from relevant ministry and government agencies to extrapolate what the dictum meant in a certain event of contemporary geopolitics.

In Bangladesh, by contrast, during its existence of 51 years, ministries or government agencies were unable to publish a single piece of an official document to dissect how Dhaka would use its perceived “friendship to all” if it were to encounter an unfriendly posture from other countries.

First of all, although in the context of the Cold War, as a member of the NAM, Bangladesh’s friendship-to-all-oriented rhetoric made some degree of aspirational sense, but in practice, it has never carried enough weight to be considered as a substantial policy. A well-crafted policy must entail a set of national core interests, priorities, and strategic planning.

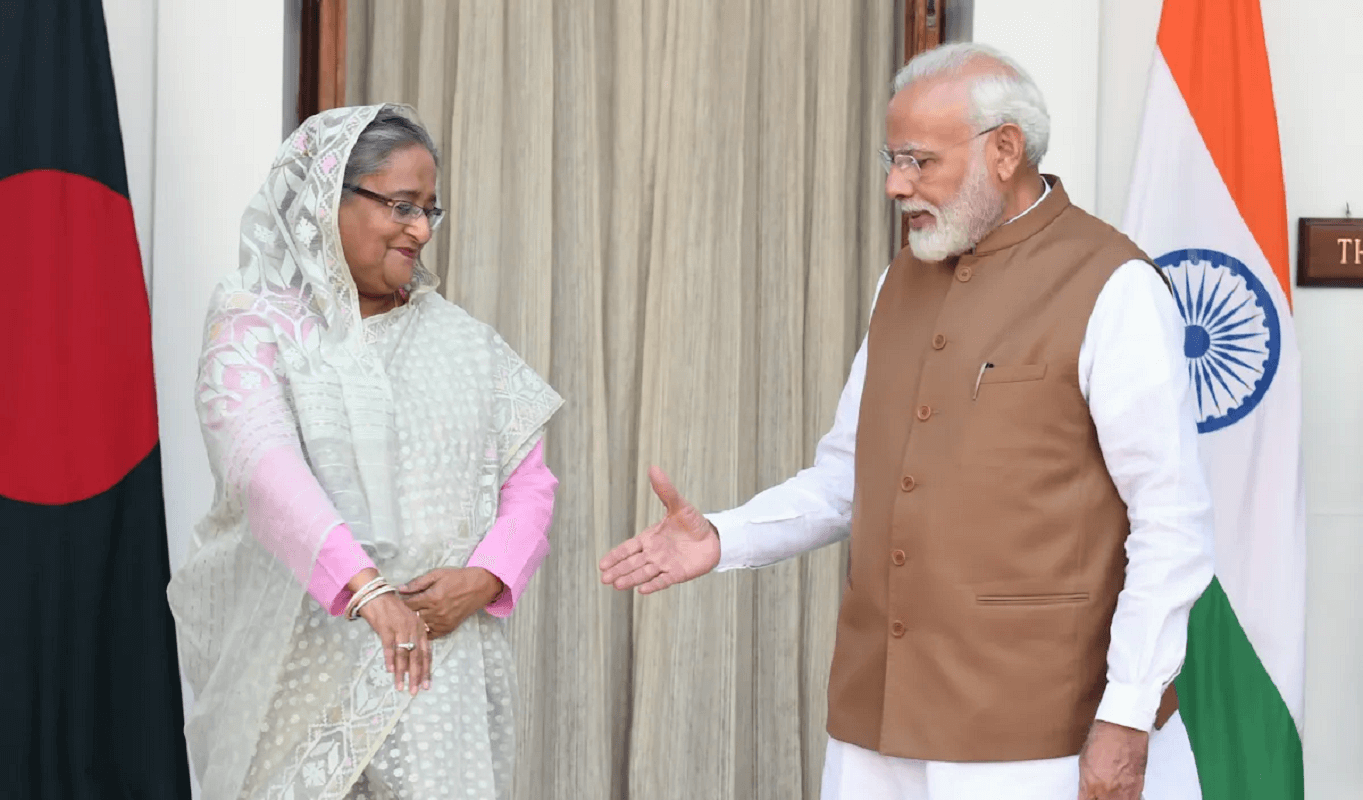

The key components of a such a policy would necessitate the modus operandi to achieve the goals that the state set to achieve within a certain period of time. Although, on a regular basis, those at the highest level of the government, including Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina herself and the foreign minister, repeatedly misquote this cliché as Bangladesh’s foreign policy, they fail to address how this friendship would apply in an unfriendly strategic environment.

Like any other state, Bangladesh has no tools to establish absolute control over the external environment to reshape other states’ behavior or intention in a way that is conducive to Dhaka. Hence Bangladesh must learn to confront geopolitics as it is, not to continue the delusional utopia of “friendship to all.”

Bangladesh’s own history with its neighbors substantiates the uselessness of the so-called “friendship to all” rhetoric. For example, Myanmar’s hostile actions on the border and coherent coercive tactics of pushing Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh as a demographic dumping ground undermine Bangladesh’s territorial sovereignty.

It is indeed Naypyitaw’s deliberate coercive tactic to gain strategic primacy over the Bay of Bengal in the longer term.

Another neighbor, India’s, continuous killing of Bangladeshi citizens aims to create a sense of domination over Bangladeshis. To complement coercion, New Delhi also deploys a set of covert-overt efforts to compel Bangladesh on India’s terms, which is clearly not an emblem of friendship.

However, even in these contentious issues with neighboring countries, Dhaka’s insistence on “friendship to all” is a folly to the national interest. Doesn’t it then send a wrong signal to hostile actors that Dhaka will stick to “friendship” even if they incur damage to Bangladesh’s national interest, and they can get away with it without paying a price? How could this conceivably be the foreign policy of a sovereign country?

Bangladesh’s own policy toward other countries also contradicts Dhaka’s insistence on “friendship to all.” For example, Bangladesh doesn’t recognize Israel as a state because of its strong ties with the Muslim world, but Israel is recognized by 165 countries in the world.

Until recently, Dhaka also did not recognize Kosovo as a country either. On the other hand, the state of Bangladesh’s relations with Pakistan is by no means friendly. Then how does “friendship to all” stand in these circumstances? It is clearly evident that “friendship to all” is just rhetoric of convenience, but in effect, it is nothing but empty words.

In particular, as the world is returning to the great-power competition where a number of the middle and minor powers are picking sides, while others are crafting their own strategic outlook to navigate intense geopolitical competition, Dhaka’s insistence on outdated “friendship to all” exhibit ill-preparedness and acute weakness of the country’s strategic vision.

By following India’s pathway to the NAM in the 1970s, Dhaka adopted the “friendship to all” mantra, but New Delhi itself recognized geopolitical reality, in the process of abandoning its decades-long so-called non-aligned policy and embracing emerging security alliances such as Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

Meanwhile ASEAN countries jointly published their own “Indo-Pacific outlook,” and even a number of non-Indo-Pacific countries, such as Canada, have adopted an Indo-Pacific policy.

Bangladesh sits in the strategic rimland of the Indo-Pacific, where it is confronting the Tatmadaw, which rules Myanmar, a country that is becoming more unstable. In addition, as US-China strategic competition has deepened, China-Japan and China-India hostility intensified as a result – and Bangladesh is at a crossroads.

Any potential conflict between India and China, due to India’s geostrategic vulnerability in the narrow Siliguri Corridor, will undoubtedly have a direct impact on Bangladesh. Should such a conflict emerge, how would Bangladesh pursue its foreign policy to protect its sovereignty and territorial integrity? What sort of strategic vision should Bangladesh pursue now to minimize the risk in such a situation? In fact, Bangladesh has no policy to navigate such a strategic conundrum.

The core of the problem is the dysfunctional politics and absence of meritocracy in all aspects of Bangladesh’s society. In Bangladesh, there has never been a distinction between the state and the ruling party in state affairs, in essence creating a government by the party and for the party as opposed to for the state itself.

The head of the ruling party, the Awami League, Sheikh Hasina, at 75, is holding the concurrent position of the head of party and government. When the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party was in power, it practiced the same pattern, as has almost every other political party that was in government since the inception of Bangladesh.

These political leaders, therefore, undertake foreign policies that serve the best interest of their corresponding parties rather than the national interest. These officials, whether bureaucrats, diplomats or security forces, are appointed primarily based on their political loyalty to the ruling party and family ties rather than based on merit and efficiency.

This practice creates a vicious cycle within the government where officials see their stakes more on regime survival than advancing Bangladesh’s national interest in the global arena. It creates a system where everyone extracts benefits from the state, but no one really owns it. This also explains why Bangladesh hass failed to establish any institutions that groom future generations’ expertise on statecraft, strategic, and security affairs – resulting now in the absence of a foreign policy for the entire nation.

In essence, “friendship to all, malice to none” is a dead-end pursuit, which died with the NAM. The priority of state policy shouldn’t be giving in to perceived friendship or invoking hostility but should pursue state affairs realistically as it is, whether to friend or foe.

A delusional utopia of making friends with everyone is unrealistic. It is a folly for Bangladesh’s national interest.

As the geopolitical reconfiguration and security architecture of the Indo-Pacific region is under way, Bangladesh, as a key rimland state, must articulate a foreign policy that serves the national interest, not the interest of political parties or a particular regime.

Anu Anwar is a fellow at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and a non-resident associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University. He is pursuing a PhD at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

This article was originally published on Asian Times.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.