South Asia’s Geopolitical Landscape is Shifting, Creating New Alliances

Chietigj Bajpaee | 05 February 2025

From Bangladesh and Pakistan growing closer to Afghanistan’s courting of India, the region’s political calculus looks more complex than ever

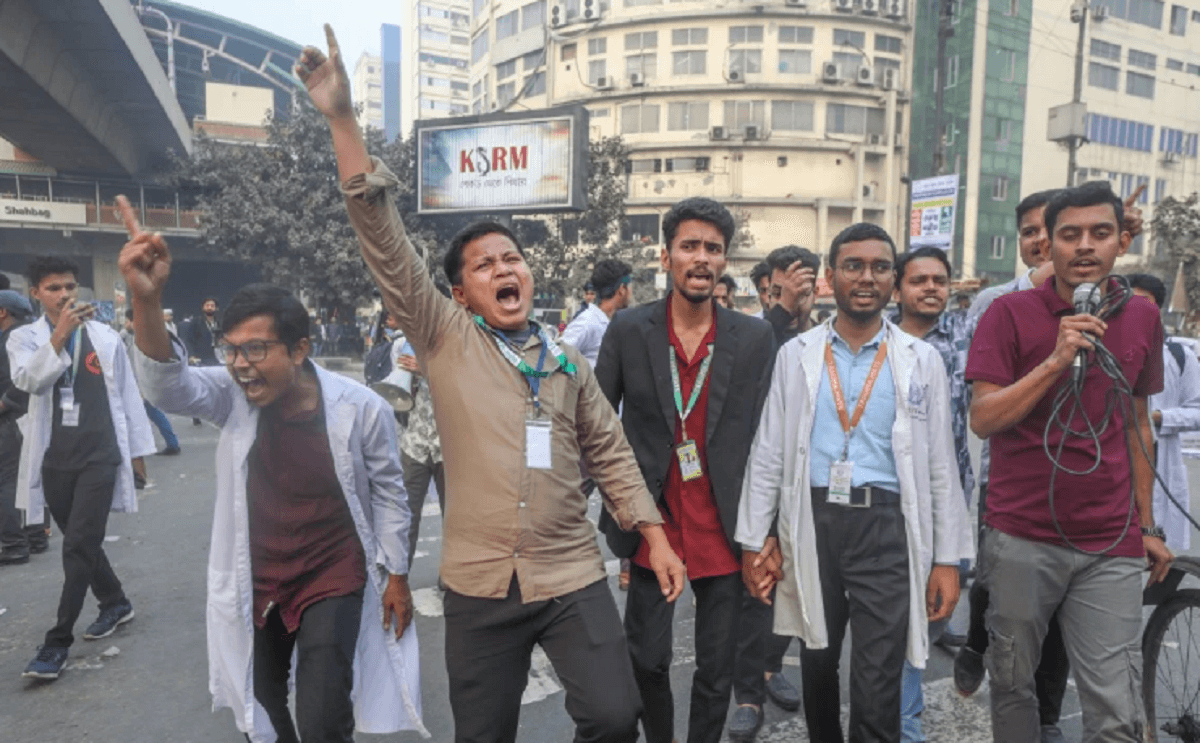

Within a span of six months, South Asia’s geopolitical landscape has undergone profound changes. Bangladeshi prime minister Sheikh Hasina’s removal from power in August was followed by the conclusion of a border agreement between China and India in October and the Indian foreign secretary meeting the Afghan foreign minister in Dubai last month. Each of these developments signal shifting geopolitical alignments across the region.

In Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina had been a key regional partner for India. Her departure has prompted New Delhi’s long-time adversary Pakistan to make inroads into the country.

Evidence of this can be seen with Dhaka’s announcement of a relaxation of visa rules for Pakistani nationals, the establishment of direct sea links between the ports of Karachi and Chittagong, and an easing of trade restrictions between both countries. This month, Bangladesh is set to participate in Pakistan’s Aman naval exercise in Karachi.

Underpinning this rapprochement is a string of high-level exchanges between Dhaka and Islamabad. This includes a visit to Bangladesh by Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar this month and the head of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency Asim Malik last month. This follows several meetings between Muhammad Yunus, the head of Bangladesh’s interim government, and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

While it would be too simplistic to view Dhaka’s relations with New Delhi and Islamabad in zero-sum terms, these developments signify a shift in Bangladesh’s foreign relations.

In particular, it represents a change of fortune for Islamabad, which had long been seen in a negative light following Bangladesh’s bloody secession from Pakistan in 1971. Under the Hasina government, opposition parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami came under scrutiny for their historically close connections to Pakistan. Now those same groups are part of, or are supporting, Bangladesh’s interim government.

The China-India border agreement has helped to de-escalate tensions following the deadly clash in 2020. The disengagement entails the resumption of patrols and grazing rights in two contested areas in eastern Ladakh and Aksai Chin. A meeting last month between Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri and Vice-Foreign Minister Sun Weidong also discussed the revival of “people-centric” initiatives.

The agreement does not resolve their long-standing border dispute, with neither side rescinding claims to disputed territories and no agreement over the delineation of their western border, known as the Line of Actual Control. A sizeable military presence remains on both sides with no signs of an imminent troop reduction.

The border deal also makes no reference to other disputed areas. Neither does it address contentious issues such as water disputes, which threaten to flare up amid Beijing’s plans to build the world’s largest dam along the Yarlung Tsangpo, or Brahmaputra, which traverses both countries.

Nonetheless, the agreement is an acknowledgement by both sides of the need to establish guard rails in the bilateral relationship as they face more pressing concerns at home and abroad.

For China, recent efforts to de-escalate tensions with neighbouring countries, including India but also Japan, signals a push to stabilise its periphery as Beijing prepares for a more pronounced strategic rivalry with the United States under a second Trump administration. For India, de-escalating border tensions is a prerequisite to renewed economic engagement with Beijing amid recognition that India cannot meet its ambitions to emerge as a global manufacturing hub without components and raw materials sourced from China.

Misri’s meeting with acting Afghan Foreign Minister Amir Khan Mutaqi is the latest sign of a gradual rapprochement between New Delhi and Kabul since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 2021. In November, the Taliban appointed an acting consul general in Mumbai after New Delhi reopened its embassy in Kabul in 2022.

Historically, New Delhi has kept the Taliban at arm’s length, given its extremist ideology and close affiliation with the Pakistani military and intelligence establishment. At one time, Afghanistan was seen as a source of “strategic depth” in Pakistan’s rivalry with India.

These concerns were fuelled by attacks on Indian nationals in Afghanistan, including at the Indian embassy in Kabul in 2009 and consulate in Herat in 2014. Now the tables have turned, with Afghanistan becoming a liability rather than an asset for Islamabad, as evidenced by a string of recent border clashes.

Taliban attracts Chinese tourists to Afghanistan in an effort to boost the economy

Underlying these developments are broader strategic considerations. Bangladesh’s foreign policy realignment is an extension of the country’s chronic identity crisis with politics swinging (often violently) between competing national identities.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban is trying to break free of its international isolation. It wants India to join the ranks of China and Russia as its development partner, particularly as the Trump administration has announced a cessation of foreign aid. For India, the Taliban represents a “lesser evil” than groups like Islamic State.

Additionally, as the only country that shares borders with every state in the region, recent developments serve to both help and hinder India’s broader foreign policy aspirations. On the one hand, New Delhi’s deteriorating relations with Bangladesh complicate India’s eastward engagement under the framework of its “Act East” policy. On the other, New Delhi’s improving relations with Kabul support India’s broader objective of strengthening connectivity with Central Asia.

A realignment of relations is under way across South Asia. Bangladesh is moving closer to Pakistan while it seeks a more balanced relationship with India. Afghanistan is moving closer to India while it seeks a more balanced relationship with Pakistan. Meanwhile, China is seeking to stabilise its periphery as it focuses on the US as the primary external threat to its security and prosperity.

Chietigj Bajpaee is a senior fellow for South Asia at Chatham House, a London-based public policy think-tank.

This article was originally published on South Asia.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.