The Incomplete End of Nepal’s Hindu Monarchy

Amish Raj Mulmi | 07 April 2025

Violent pro-monarchy protests reveal Nepal’s incomplete transition from Hindu kingdom to secular republic, with nationalist myths and India’s Hindu Right feeding into royalist resurgence

IN 1979, in the reign of Birendra Bir Bikram Shah, the Nepali monarchy instituted a few reforms to address popular demands for better political representation. A public referendum, now widely seen to have been rigged, delivered a verdict in favour of continuing the prevailing Panchayat system of rule, a partyless order of governing councils that left the king as the ultimate authority. In the aftermath, Birendra made a few concessions, such as allowing direct elections to the National Panchayat. The first of these was conducted in May 1981 – Nepal’s first general election, of a kind, since 1959.

In a 1983 assessment, the Unites States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reported that the “largely cosmetic” reforms had “only bought time for the monarchy”, and that the challenge lay in balancing “elite interests with aspirations of newly politicized groups eager to benefit from participation.” It was a prescient take. The reforms did not last the decade. In 1990, after mass protests, the Shah autocracy had to make way for a multi-party democracy and constitutional monarchy.

The CIA was also of the view that Birendra’s “liberalizing instincts are offset by a natural tendency – reinforced by conservative members of his family – to preserve his power.”

It thought Birendra’s queen, Aishwarya, and his brother Gyanendra were “hardliners” who would “certainly halt the reform process and reassert royal authority.” Gyanendra “may consider himself better qualified for the throne than his brother … has a greater ability to command, strike hard deals, and reward personal loyalty than the King. We believe he would relish the royal role.”

We have been covering Nepal for the last 35 years. Support our commitment to Southasian journalism. Become a Patron to support Himal!

Gyanendra got to try his hand at kingship after Nepal’s 2001 palace massacre, when the crown prince wiped out most of the royal family. (In the early 1950s, Gyanendra had been briefly placed on the throne by Mohan Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana, the last in a hereditary line of autocratic prime ministers who had ruled with the Shah monarchs as puppets.) Seven years into his reign, at the end of a drawn-out civil war, he was forced to step down as Nepal transitioned from a Hindu kingdom to a democratic republic. Gyanendra’s belief in his suitability to rule outlasted this setback. He told an interviewer in 2012 that he hoped to return as king, and he continued occasional tours of the country – the latest came in March this year – rallying Nepal’s remaining stump of monarchists around him. This February, on the eve of Nepal’s Democracy Day, he called on the public to extend its support “for the prosperity and progress of the country.”

After pro-monarchy protesters ran amok in Kathmandu on 28 March, however, the former king has gone silent. The violence left two dead – including a television journalist incinerated inside a building set on fire – and many more injured. The protesters also torched the office of the Nepal Communist Party (Unified Socialist), attempted to burn down the office of Nepal’s main Maoist party, looted a department store and destroyed numerous vehicles. There are reports that locals prevented the rioters from doing even worse. An overnight curfew had to be imposed for part of the city, and the Nepal Army was briefly deployed to help restore order. The security forces have been questioned for their forceful and disproportionate response to the protests. The commander of the “royal task force”, Durga Prasai, tried to ram police officers with his pick-up truck. He is now absconding after a warrant was issued for his arrest.

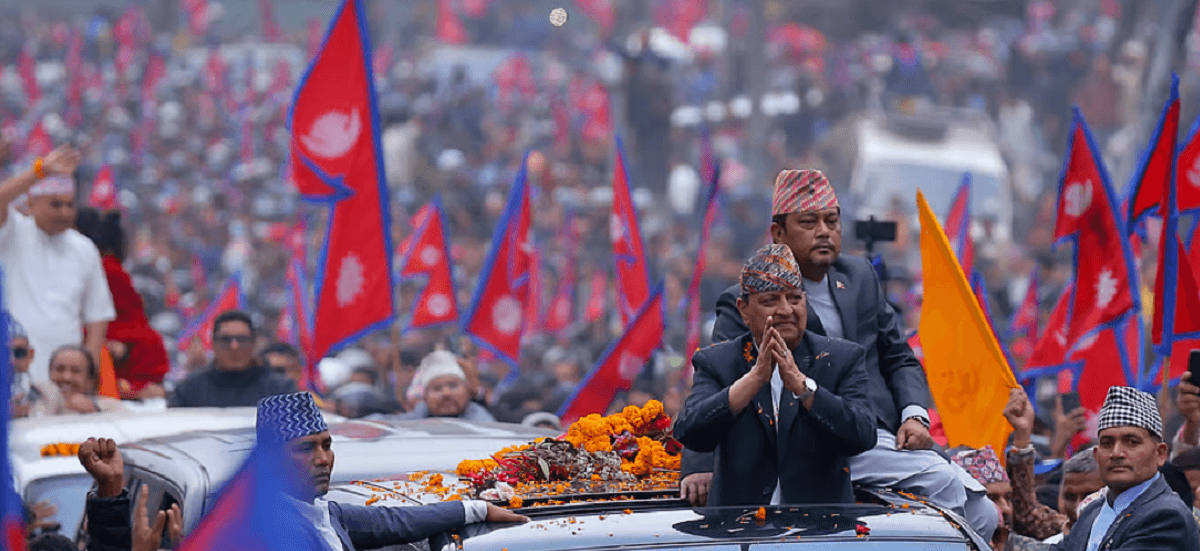

Earlier in March, the prospects of Gyanendra returning to the throne had been boosted by perhaps the largest gathering of royalist forces since the abolition of the monarchy. Eyewitnesses suggest a crowd of nearly 10,000 people greeted Gyanendra upon his arrival in Kathmandu from the city of Pokhara. The government had, until now, permitted peaceful pro-monarchy gatherings in the name of free speech. But the recent violence has turned the tide. More than a hundred people who participated in the rioting have been arrested. Nepal’s major political parties, barring pro-monarchy outfits, want the king to be held to account, if not by charging him with incitement to violence then at least by stripping him of the facilities and privileges he enjoys as a former head of state.

Gyanendra and Nepal’s royalists had so far taken pains to maintain civility, but that pretence is now gone. The limited but not insubstantial public sympathy they had gathered – helped by deep popular anger with Nepal’s current political leaders – has dissipated.

Nepali commentators see the resurgence of royalist forces as a symptom of increasing discontent with the country’s political and economic status quo. Nepal’s economy has not fully recovered from the ravages of the pandemic. Thousands of young Nepalis leave the country every single day for better economic opportunities abroad. None of the country’s political parties – including the main establishment forces currently sharing power, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) and the Nepali Congress – have shown any inclination for much-needed structural reform. Instead, crony capitalism is rampant, as is corruption.

Yet for all the present anger, on almost every indicator – economic, social or political – Nepal is doing better than it ever did under the monarchy. In 1995, at the peak of the era of constitutional monarchy, 55 percent of Nepalis lived in extreme poverty. That figure had dropped to less than 0.5 percent in 2023. Although Nepal’s economy grew slower between 1996 and 2023 than those of most Southasian countries, personal incomes have risen for all demographics. Local governments have shown a clear preference towards decentralisation. There is freedom of speech on a scale unheard of under the monarchy.

Why, then, are some sections of Nepali society nostalgic about royal rule?

ONE COULD DIVIDE those leading the call for the monarchy’s return into five categories. The first is the old ruling elite, especially those among them whose fortunes have declined under the republican order. This includes businesspeople who profited from their connections with the royal family, some of whom were signatories to a letter issued before the recent riot that said the government would be held responsible should the situation get out of control.

The second category comprises the pro-monarchy Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) and its affiliates. Some of this group have tasted power under both the king and the republic. Kamal Thapa, an RPP stalwart, was Nepal’s home minister between 2002 and 2006, a time that saw a massive escalation in violence as part of the civil war. He was later a minister in republican governments, reinforcing the idea that ideology is less important than position in Nepali politics. The RPP’s current head, Rajendra Lingden, emerged in the republican era, and pushed Thapa out of the party in 2022. (Thapa now leads a breakaway faction.) Lingden has cut deals with non-royalist parties as a means to power, and was the deputy prime minister in a previous government.

The third category consists of relatively new political actors such as Durga Prasai, Rabindra Mishra and Manisha Koirala. Prasai, a controversial businessman, was once close to K P Oli, the head of the CPN (UML) and Nepal’s current prime minister, before he broke away and turned to the royalist camp. Mishra, a former journalist, earlier led the Sajha Party, a liberal outfit founded as an alternative to Nepal’s old political establishment, but he switched over to the RPP in 2022. Koirala, a former Bollywood actor, is the granddaughter of Nepal’s first democratically elected prime minister, B P Koirala, whose arrest in 1960 marked the beginning of autocratic Panchayat rule. This group uses its social media clout to gather support for the monarchy.

The fourth is made up of Hindutva groups often influenced by the Hindu Right in India, from which they draw their ideology. For them, Nepal’s present status as a secular republic is an affront to its ostensibly Hindu identity, and the Shah king is a Vishwa Hindu Samrat – a “World Hindu Emperor”. This group includes ascetics and religious leaders like Pushkar Khatiwada, who was arrested for throwing stones at security forces during the recent rioting.

The fifth category contains assorted groups and individuals disenchanted by the republic and retaining sympathy for the old ways, a disillusioned lot for whom multi-party politics has not brought much benefit. This group primarily comprises members of Nepal’s dominant hill castes – an old elite for whom the king remains a symbol of a unified Nepal, and who feel challenged by the increased representation of marginalised communities in the republic.

These five groups are not discrete. They often overlap and intersect, and sometimes also compete with each other. Some of them have underplayed their monarchist sympathies since the advent of the republic. These groups are as full of complications and contradictions as Nepal’s democratic forces. For instance, this March, a committee formed to lead the push for the monarchy’s return fell prey to infighting, with particular leaders convinced they deserved credit for the revival of royalist politics. Before the rioting, discontented factions attempted to stir up trouble by spreading misinformation about the Nepal Army, an institution they believe remains loyal to the crown. The army had to put out a statement reaffirming its commitment to Nepal’s republican constitution.

A point of special concern for Nepal’s democratic leaders has been the appearance at royalist rallies of posters showing Ajay Mohan Singh Bisht, better known as Yogi Adityanath. There are legitimate fears over whether Bisht, a Hindutva hardliner and the chief minister of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, has backed the return of the king. Bisht and Gyanendra have had multiple meetings, and these carry special resonance because Bisht is also the mahant of the Gorakhnath math.

The temple in Gorakhpur, tied to the medieval Hindu ascetic Gorakhnath, has history with the Nepali monarchy. Putative connections between Gorakhnath and the Shah dynasty appear apocryphal: he likely lived in the 12th century, long before the Shahs first made their mark as the rulers of Gorkha, in what is now central Nepal. But Gorakhnath is one of the three tutelary deities of the Shah dynasty, and ascetics from the Nath sampradaya, the sect founded by Gorakhnath, have historically shared a close relationship with the Shahs. They have been made administrators, given land grants, and on one occasion in the 18th century a Nath ascetic was honoured by Prithvi Narayan Shah, the most iconic of the Shah kings, for his assistance in the military campaign that unified Nepal. Gyanendra’s proximity to Bisht is an outcome of these linkages.

Bisht has not weighed in on the recent pro-monarchy agitations in Nepal, but in the past he has called for the return of a “Hindu rashtra”, or Hindu kingdom, in Nepal. In using his image in their demonstrations, the monarchists are engaged in a strategic calculation. It has been widely assumed – and reported – that Bisht will be the eventual successor to Narendra Modi as the prime ministerial candidate of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The monarchists are betting on this, assuming that New Delhi under Bisht will support not just the reinstatement of a Hindu Nepal but also the return of the Shah king.

The monarchists are also looking at the traditional relationship between the Shah dynasty and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – the BJP’s organisational parent and the fountainhead of the Hindu Right. In the 1960s, Birendra and Gyanendra’s father, Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah, believed links with the RSS would make for mutual benefit. Mahendra was not on good terms with the Indian government of the time, led by the socialist and secular Jawaharlal Nehru. As earlier detailed in this magazine, the RSS “helped Mahendra to cultivate the Hindu forces as his supporters in India. For the RSS, Nepal, as an active Hindu monarchy, was the playing-out of its fantasies of a Hindu rashtra, unpolluted by foreign (read: Christian or Muslim) invasion.”

In January 1963, the head of the RSS, M S Golwalkar, met with Mahendra and invited him to an RSS function in India. After controversy in India over Mahendra’s apparent support for the then-proscribed organisation, the visit never materialised. Nonetheless, the RSS continued to maintain links with the Shahs. It declared both Birendra and Gyanendra to be Vishwa Hindu Samrats. It also established the Vishwa Hindu Mahasangh in Nepal, as well as the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, its international arm.

Between them, Bisht and the RSS are seen as critical to the return of the monarchy in Nepal. The RSS, some argue, may be more keen on Nepal becoming a Hindu republic, without the king – something even sections of the ostensibly secular Nepali Congress have recently batted for. But the spectre of an Indian hand behind a resurgent monarchy haunts the majority of Nepal’s political leaders, who have good reason to fear New Delhi’s interventionism.

The current mistrust between New Delhi and Kathmandu has not helped matters. Oli, who returned to power last June, is seen as being closer to China than to India, and has not hesitated to use anti-India sentiment to his political benefit. Oli is also seen as the progenitor of the current India–Nepal border dispute. New Delhi has further remained circumspect in Southasia since the overthrow in Bangladesh of Sheikh Hasina, whose autocratic regime it supported to the end. Informal discussions, including ones between the foreign ministers of Nepal and India, suggest New Delhi remains committed to Nepal’s democracy.

Any parallel diplomacy to the contrary by Bisht or the RSS and its affiliates risks a conflagration in Nepal–India ties. Meddling from Bisht, if any, could stoke speculation that all is not well between Modi and his point man in India’s most populous state

Members of the RSS and its affiliates have propagated the idea that Nepal’s current monarchist upsurge is part of a battle between atheist communists aligned with China and Hindus aligned with India. This is a grave error. India must remember that the Shah dynasty formed links with the RSS not as an expression of ideological similarity or Hindu affinity, but rather due to the monarchy’s anti-Indianism at a time when India was ruled by the secular Indian National Congress. Nepal’s kings have rarely been on friendly terms with New Delhi except for the briefest periods of tactical alignment – as, for instance, when Nehru backed the Shah monarchy in the early 1950s as part of a democratic push to overthrow the dictatorial Rana regime. Nepali nationalism as promoted by successive kings – and also by the civilian politicians who replaced them – has been rooted in an aversion to India. New Delhi would do well to back a republican Nepal if only to forestall a resurgence of such nationalism in its neighbourhood.

NEPAL UNDER THE KINGS, with power firmly centralised in royal hands, was a deeply impoverished country that failed to deliver almost any improvement to the lives of its people. Poverty rates remained nearly the same between the mid 1970s and mid 1990s, the years when Birendra – perhaps Nepal’s most liberal king – held the throne. Marginalised Nepalis enjoy better representation under republican rule than ever before, although much more still needs to be done to redistribute power beyond the old elite.

Attributing the recent resurgence of monarchist politics to popular discontent, as many have done, tells only part of the story. For the rest of it, we need to go back some 20 years, to the beginning of the peace process at the end of Nepal’s civil war, when the country had just begun to embrace the ideals of a federal, secular republic.

Oli, the current prime minister, had expressed scepticism even at the time about the transition to a federal republic – which helps explain why many of its key goals, including the decentralisation of authority, are still yet to be fully realised. Nepal’s politics is notoriously geriatric-driven, and a good deal of today’s politicians, including the prime minister as well as the chair of the Nepali Congress, Sher Bahadur Deuba, were also active under the monarchy. Even when they are glad to have shed the king, they have not shed much of the baggage that came with him.

The centralising tendencies of Nepal’s political leadership have not dissipated, nor has its elite ethnic and caste character changed much. Both these distinguishing marks are legacies of the years of royal rule. Nepal’s fledgling provinces totter on the edge of dysfunction, feeding a critique of federalism as a waste of taxpayer’s money. But none of Nepal’s eight governments since 2015 has transferred to the provinces the powers they are due under the constitution, including control over the police and provincial administrations. Local governments, perhaps the most effective antidote to centralised authority, face a shortage of manpower. With a central political leadership unwilling to implement real federalism, the republic’s foundations have been whittled down.

Meanwhile, Nepali historiography has not evolved much since the days of the monarchy. The national history many Nepalis receive today remains as it has been for many decades: a long procession of kings and their achievements, with barely a bad word about any of them or their reigns. A proper post-monarchy revision of Nepali history is yet to be attempted, both in the education system and in common discourse.

Nepal’s contemporary nationalist discourse was framed by the monarchy during the Panchayat years. A core part of this, beyond highlighting an image of martial bravery, was the promotion of Nepali as the sole language, and of the culture of the elite hill castes as the national norm. The idea of Nepal as a dominant-caste Hindu hill state has persisted despite the advent of the republic, because the republic’s leaders are themselves steeped in the old nationalist discourse.

In many ways, Nepali historiography stopped at the turn of the millennium. The civil war is remembered as a violent insurrection without explaining its roots and its popularity among the landless classes and marginalised ethnic groups. Very few like to point out that some 7000 Nepalis died in the civil war across 2002 and 2003, shortly after Gyanendra ascended to the throne and ordered operations to crush the Maoists insurgency. Fewer still point out that the majority of these deaths were attributed to government forces. As Human Rights Watch noted in 2005, Gyanendra’s mobilisation of the Royal Nepal Army against the Maoists “markedly increase[d] the war’s lethality, particularly for civilians … Nepali security forces continue to enjoy near total impunity from prosecution for human rights abuses. Despite international pressure, the military have not instituted any credible system of accountability for hundreds of outstanding cases of abuses.”

The Madhesh movement, a struggle for dignity and justice by marginalised people of Nepal’s southern plains, has today become a mere footnote in the larger narrative around the promulgation of Nepal’s republican constitution in 2015 and the subsequent border blockade by India. A recent Nepali film was censored for its use of a video clip that showed Oli calling Madhesi parties protesting against the constitution at the time “rotten mangoes” – a sadly common example of Nepal’s hill-based elite denigrating the Madhesi people.

The ethnocentric character of the Nepali state has remained unchanged despite the abolition of monarchy, as has so much else that the monarchy set in place. The foundational ideas and myths of royal rule continue to have credibility and bring comfort among significant sections of Nepali society. And now, unsurprisingly, the royalist narrative has come home to roost. Most societies that shed an old authoritarian or colonial power – see Nepal’s two neighbours, China and India – also reject past historical narratives in favour of new ideas and stories about themselves. These may in turn be contested and problematic, but they allow a people to reimagine themselves. Republican Nepal has not done this. Instead, today’s politicians still use the idioms of Panchayat nationalism. It is not surprising, then, that even many younger Nepalis are still brought up on the Panchayat fever dream, with an absolute monarch embodying the state and the nation.

Discontent, then, does only so much to explain the revival of royalist politics in Nepal. Really, the revival is a result of Nepal’s incomplete revolutions. Historical memory has never been more important. The 2006 revolution, which brought down the king, was vastly different from the revolutions of 1950 and 1990. In the latter two, Nepal adopted multi-party politics, but supreme constitutional authority remained invested in a single person, who frequently abused it at will. In 2006, Nepal decided that only its people could be the ultimate authority. Nepalis made the nation, and not the other way around, as the Panchayat slogan of EkDesh, EkBhesh, Ek Naresh – One Nation, One Dress, One King – would have it. This radical shift, which changes the entire paradigm of what makes Nepal a state, has never been fully realised by either the country’s leaders or its people.

The roots of the modern republican state may go back to 18th-century France but the application of its ideals is individual to every state that embraces the concept. Nepal chose to become a republic because it was the only way in which the rights of all its people, and not just of those close to the institution of the king, could be assured. A lot still needs to be done – just this February, a Dalit family’s home was demolished by a ward chief and his cronies preparing for a mahayagya on the grounds that the family’s presence nearby would sully the Hindu ritual – but the rights that Nepal’s people are entitled to today are not some benevolence granted by their monarch. Instead, finally, these rights are intrinsic to every Nepali citizen.

The monarchists battling for the return of the king do not want this. They want to return to an archaic form of governance that operates on royal preference and whim. The recent rioting suggests they are willing to test the limits of the republic, because they know parliamentary politics will continue to reject their beliefs. If Nepal does not, after such violence, nip pro-monarchy politics now and set straight the skewed public memory that sustains it, the king and his cabal will constantly threaten the foundations of the republic.

Amish Raj Mulmi is the author of All Roads Lead North: Nepal’s Turn to China (2021). His writings have appeared in Al Jazeera, Roads and Kingdoms and Mint Lounge, among other publications. He is a consulting editor at Writer’s Side Literary Agency and a contributing editor at HimalSouthasian.

This article was originally published on Hemal.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.