Russia’s War Has Unified Europe’s Opposing Sides

The invasion of Ukraine has finally reconciled Europe’s liberals and nationalists.

Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard | 20 March 2023

On one of the last days of June 1914, a telegram arrived in a remote garrison town on the border of the Habsburg Empire. The telegram consisted of a single sentence printed in capital letters: “HEIR TO THE THRONE RUMORED ASSASSINATED IN SARAJEVO.” In a moment of disbelief, one of the emperor’s officers, Count Lajos Batthyany, inexplicably began speaking in his native Hungarian to his compatriots about the death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir and a man who had been perceived as partial to the Slavs. Lt. Josip Jelacich von Buzim, a Slovene who felt uneasy about Hungarians—especially because of their suspected disloyalty to the throne—insisted that the conversation be held in the more customary German. “Then I will say it in German,” the count assented. “We are in agreement, my countrymen and I: We can be glad the bastard is gone.”

This was the end of the multiethnic Habsburg Empire—at least the way Joseph Roth captured it in his magisterial novel Radetzky March. And the Habsburg experience has often been replicated in the European Union. Unity has usually been the first casualty of crises in Europe. During the Iraq War, the euro crisis, and the refugee crisis, for example, the EU quickly fragmented into different camps and countries.

And Russian President Vladimir Putin had good reasons to imagine that the same would happen the day his army invaded Ukraine. The war was an existential threat for Ukraine’s neighbors, such as Poland or Estonia, but a faraway conflict for Portuguese or Spaniards. Europe’s energy dependence on Russia made a confrontation with Moscow a high-cost exercise in a moment when European societies experienced hard economic times. And, in any case, Europeans can have common dreams, but their nightmares are strictly national. The rise of anti-German sentiments in the early weeks of the war was a glimpse of what the scenario from hell could have looked like.

But one year into the conflict, we can see that the Kremlin’s expectations were wrong. A recent survey by the European Council on Foreign Relations shows that, against expectations, European publics’ views on the war have converged rather than diverged. Compared with May last year, the proposition that the war between Russia and Ukraine should end as soon as possible, even if that means Ukraine losing part of its territory to Russia, is no longer that popular among Europeans. The opposite idea—that Ukraine should regain all its territory, even if that means a longer conflict—currently prevails in Europe on average, and in 5 out of 10 countries that we have polled, including France. Europeans also report an improved perception of European and American power—while many see Russia as weaker than they had previously thought.

The reasons for the increased support for Kyiv probably diverge from country to country, but at least four factors are of particular importance. Putin’s strategy of mass destruction has morally outraged most Europeans. Ukrainian military victories in the summer and autumn of last year have convinced many that Kyiv can win the war. A warm winter and European governments’ successful handling of the energy crisis have increased the sense that the EU is stronger than many believed. And U.S. President Joe Biden’s determination to do what it takes not to allow Russia to win is another critical factor for the new European position on the war.

But the war has also brought about a less recognized but critically important political realignment in the domestic politics of many European countries. To put it bluntly: The war reconciled many European nationalists to the idea of a stronger and more united EU, while at the same time forcing many pro-European liberals to discover the mobilizing power of anti-imperial nationalism.

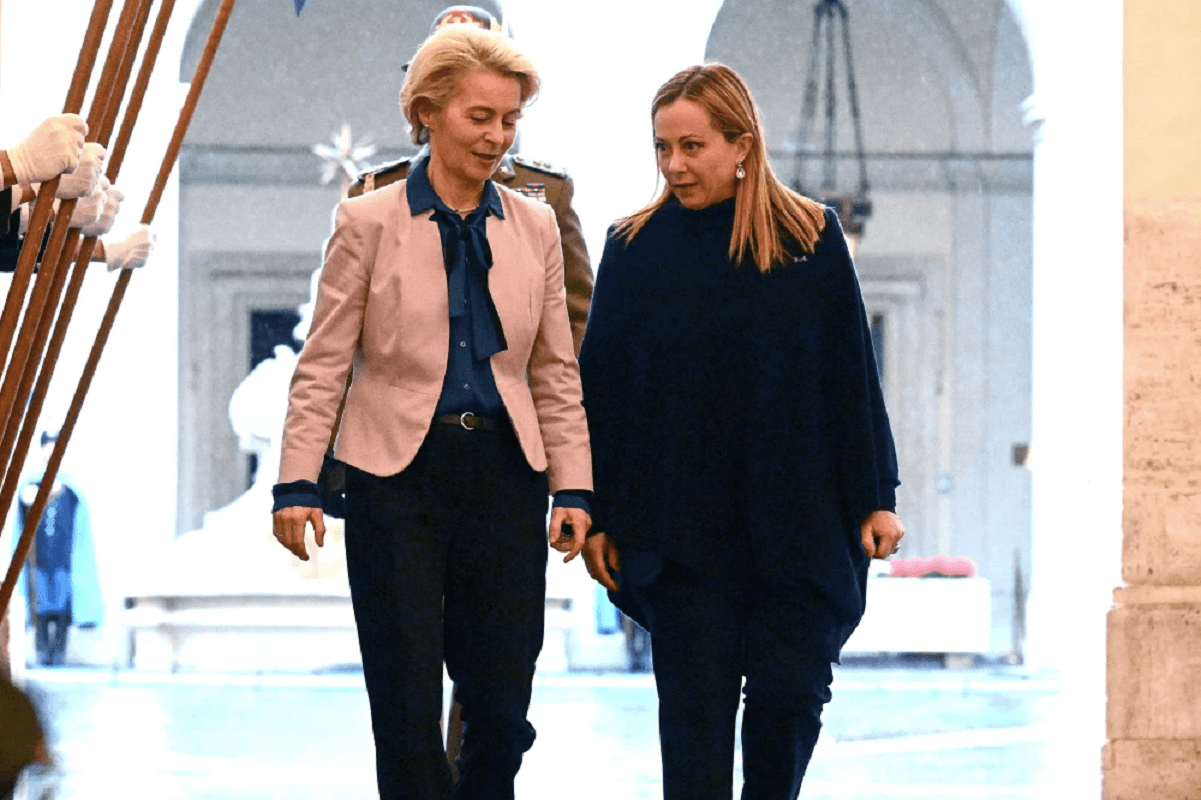

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and her party Brothers of Italy are the most powerful representatives of the first trend. Until very recently, the Italian far right viewed Brussels as the biggest threat to Italy’s sovereignty and identity. They flirted with leaving the euro and even the entire European Union. But today, they see Brussels as a valuable ally in defending Italian sovereignty from superpowers such as China and Russia and borderless threats such as COVID-19.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the most pro-European, cosmopolitan, and liberal forces in Europe have been inspired by Ukraine’s struggle for survival and are rethinking their positions on the idea of nationalism and military spending. Looking at the breakdowns of party members shows an incredible convergence of nationalists and liberals on how they see the war. The percentage of supporters of liberal French President Emmanuel Macron who believe that only a Ukrainian victory can bring lasting peace in Europe is identical to the percentage of supporters of the right-wing Law and Justice party in Poland who believe the same. At the same time, the German Greens, the party that most embodied the country’s pacifist tradition, are not far behind LREM and PiS.

And most interestingly, the strongest supporters of the Ukrainian struggle are the bureaucrats in Brussels. Confronted with Putin’s aggression, European Commission President Ursula von Der Leyen embraced the Ukrainian struggle for survival as her own. She was the person who pushed to use European funds to buy weapons for Ukraine. And she advocated for Ukraine to be given an EU membership perspective. This is maybe the ultimate act of political fusion—marrying the ethno-nationalist militarism of Kyiv’s fight for survival with the post-national, legal processes of the EU. If Kyiv’s 2013-14 Maidan demonstrations sought legitimacy by flying European flags, now European capitals are finding a new sense of purpose and legitimacy by draping themselves in Ukrainian flags. Anti-nationalist Brussels has suddenly been mesmerized by the power of civic nationalism. In their worship of the Ukrainian leader, European liberals have broken with playwright Bertolt Brecht’s post-nationalist dictum, “Unhappy the land that is in need of heroes.”

It is fair to admit that the reconciliation between liberals and nationalists was visible already in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, when liberals did not hesitate to close borders while nationalists in power realized that managing the pandemic meant taking care of all those who happened to be within the borders of their states regardless of where there were born. But it was Polish nationalists welcoming millions of Ukrainians that probably more than anything else forced both left and right to adjust their views for the age of Putin.

But while the European unity achieved in this last year in remarkable, it cannot be taken for granted. It could be eroded by the reversal of any of the trends that have brought Europeans together: a successful Russian military counter-offensive, or the rising costs of living and hosting refugees (now the dominant fears in Italy, Germany, and France).

The biggest threat to the new marriage of nationalists and cosmopolitans comes from outside the EU, however. Ironically, it has less to do with Moscow than with Washington. One of the major effects of the war has been to expose Europe’s dependence on the United States’ security umbrella. But while the confrontation with China looks like a bipartisan issue in the United States, the risk of a U.S. foreign policy split over Russia is real. Former U.S. President Donald Trump tends to see Putin’s war in Europe as Biden’s war. His readiness to sacrifice Ukraine could cause a major change not just in the way that Europeans see the future of the war, but even in how they see the future of the EU.

If Trump successfully becomes the leader of an anti-war party, we could see a rapid reverse in the foreign policy convergence of European liberals and nationalists. European unity survived Russia’s military, but can it withstand America’s politics?

Ivan Krastev is the chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies in Sofia, Bulgaria, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He is the author of Is It Tomorrow, Yet? The Paradoxes of the Pandemic.

Mark Leonard is the co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations and author of The Age of Unpeace.

This article was originally published on Foreign Policy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.