Ukraine: Putin’s ‘Reality’ … and The Real World

Frank Hoffer | 30 June 2024

A proposal for a ceasefire from Ukraine would not only stem the bloodshed but allow it to win the peace.

Russia is ready for ‘peace negotiations on the ground of reality’, its president, Vladimir Putin, announced this month—before instantly naming unrealistic maximum goals. The west and Ukraine immediately rejected Putin’s demand for further territorial concessions, regime change in Kyiv, ‘demilitarisation’, the lifting of sanctions and exclusion of Ukrainian membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Putin’s demands are not only uncompromising and contrary to international law. They have nothing to do with the reality on the ground:

•Ukraine is already a close partner of NATO. To be clear, it is a de facto member.

•The government in Ukraine is chosen by the people of Ukraine. Putin has no way of influencing, still less deciding, who governs in Kiev.

•Russia has no capacity to force the west to lift the sanctions and has no access to $300 billion in Russian foreign assets. Those funds are in the hands of the west and are lost to Russia but available for the reconstruction of Ukraine.

•Russia occupies part of Ukraine but by no means the entire territory of the four oblasts it has annexed on paper.

A ceasefire based on reality would therefore mean, on the one hand, Ukraine’s NATO membership, democratic elections in Ukraine and the use of the appropriated Russian assets for reconstruction, with sanctions continuing as long as Russia does not sign a peace treaty with Ukraine. On the other hand, Russia would continue to occupy the conquered parts of eastern Ukraine that have been devastated by Russian bombs, contrary to international law. What the Russians bombed, they would have to rebuild themselves. How many Ukrainians would still want to live there under Russian occupation or prefer to set off for free Ukraine is however an open question.

Ukraine cannot win the war against Russia but it has every chance of winning the peace as soon as the guns fall silent. Russia, which has been run down by Putin over 25 years, has proved incapable of enabling a good life for its citizens and developing the country. The war may stabilise Putin’s regime but in peacetime its inadequacy will lead to discontent. A Ukraine that recovers and develops with western help, by contrast, has the potential to become a convincing democratic counter-model—comparable to the superiority of the old West Germany over the Deutsche Demokratische Republik or South Korea over North Korea. Ukraine can win the economic, political and cultural competition with the Russian klepto-dictatorship if it succeeds in getting its own corruption under control and the west is ready to support an industrial strategy to rebuild the Ukrainian economy.

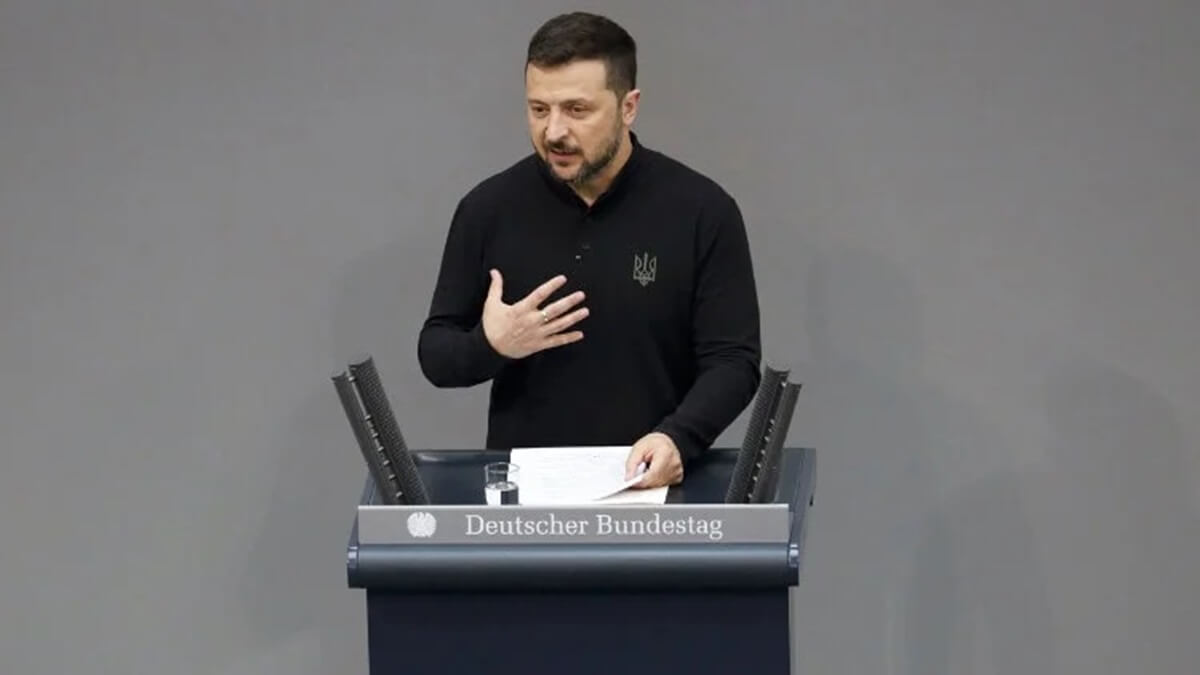

The ten-point peace plan advanced by Ukraine‘s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, is undeniably morally justified but no more realistic than Putin’s ideas. In contrast to the increasingly illusory solution of wanting to achieve the complete liberation of Ukrainian territory through years of war, a ceasefire on the basis of the above-mentioned realities would not only be a way to end the thousands of deaths and stop the threat of military escalation but also the best chance to win ultimately through peaceful reconstruction.

Bringing Putin down to earth

The question remains as to how Putin can be brought down to earth. No one has a clear answer to this. Yet while little emerged from the conference organised by the Swiss this month, hardly any government in the world could refuse to support such a far-reaching peace concession by Ukraine. A readiness not to recognise the land grab in any way but to renounce the goal of military reconquest would have the potential to isolate Russia internationally. China, India and other states which have so far behaved as pro-Russian or neutral in the conflict would be under pressure to influence Russia to stop the shooting. Parallel to such a proposal, it would have to be signalled to Putin that, in the event of rejection, Russia would have to prepare itself for even more extensive, massive and resolute military support for Ukraine.

There is undoubtedly a danger that Putin will feel strengthened in his aggressive foreign policy if he keeps a significant part of Ukraine under his control. But there is also the danger that a Russia militarily driven out of the occupied territories would work with all its might for revenge—just as a German war of revenge was already laid out in the Treaty of Versailles.

There is little reason for the Ukrainians to trust Putin in a ceasefire, as he could use the time to replenish his forces for another attack. Similarly, Putin will fear that any pause would give Ukraine the breathing space to try to reconquer the seized territories with the help of western rearmament. Mutual deterrence and defensive rearmament seem inevitable in a first phase, so that those who mistrust each other do not dare break the fragile ceasefire and a further advance by Russia is ruled out. From there it is a long way to come to a rapprochement at some point.

Whether, how and when this can be possible is not only speculation today but utterly premature in view of the realities on the ground. But that such ways can be found is shown by historical examples, from Franco-German reconciliation to the peaceful end of the apartheid regime in South Africa to economic co-operation between Vietnam and the United States.

Risk of escalation

Is it permissible to make such a proposal, which accepts the land grab by the dictator in the Kremlin as an injustice that cannot be changed at the moment? Those who would say an indignant ‘no’ to this must believe that the war can be won militarily, or at least that Ukraine can significantly improve its position on the battlefield, and they must underestimate the risk of an ever-increasing spiral of escalation. (Threats by Putin to arm North Korea or the Houthi rebels in Yemen show that there are also plenty of dangerous options for escalation beyond the Ukrainian battlefield.)

I do not share this optimism. Nor do I want to have to rely on Putin’s reasoning that, even if he is losing, he should refrain from escalating to the nuclear option.

After all the sacrifices, can the Ukrainian president articulate such a proposal without losing the trust of his people, especially of the fighting men and women? If anyone can do it, he can.

Frank Hoffer is non-executive director of the Global Labour University Online Academy.

This article was originally published on Social Europe.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.