Unholy Alliance: Myanmar’s Mercedes Monks and the Men in Green

Aung Zaw | 11 June 2024

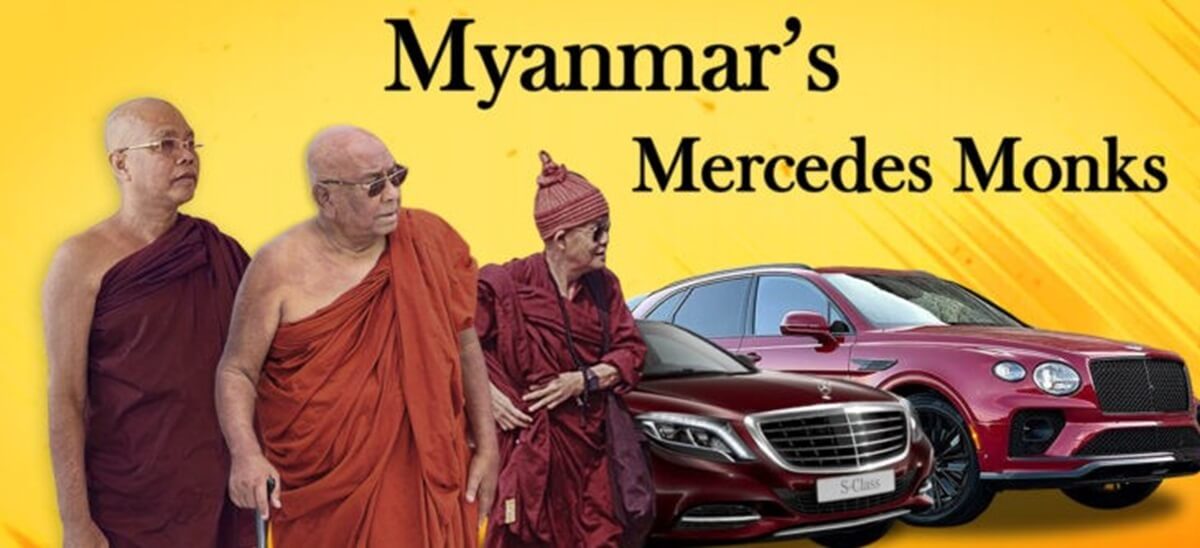

If you happen to be strolling around downtown Yangon or Mandalay anytime soon, the sight of a senior Buddhist monk cruising by in the latest Mercedes or Bentley might well cause you to do a double-take. But don’t be surprised. This is post-coup Myanmar. Abbots who support the regime have seen their cash flow increase along with their influence, as the generals make a show of embracing Buddhism and dole out handsome rewards to the monks who help them do so.

Increasingly, however, these opportunistic mendicants are coming under fire from the public, earning epithets such as “cele-monks” and “crony monks” and becoming the targets of popular boycotts.

The country’s oppressed people, activists and opposition politicians have taken note of the well-known abbots who have publicly supported the coup while remaining silent on the regime’s violence and atrocities across the country. Myanmar’s Buddhist monks were once known for their political activism, first as agitators challenging British colonial rule and later standing up to the regimes that preceded the current military junta. Today, many monks, especially senior and influential ones, are facing questions about their political stances, unaccountable wealth and the flourishing businesses they have built in recent decades.

It is a marriage of convenience. Military leaders offer cooperative monks wealth and protection. In return they gain a measure of legitimacy, portraying themselves as protectors of Buddhism, safeguarding it from what they claim is a threat from the spread of Islam in the Buddhist-majority country.

Myanmar’s highly vocal faction of conservative and ultranationalist monks offered its full backing to the military well before it staged the coup in 2021. To help it play the religion card more effectively, the military has for years cultivated a strong connection with the ultranationalist group the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, known as Ma Ba Tha.

Founded in 2012, the organization, led by ultranationalist monks, has been accused of stoking sectarian tensions in Myanmar and contributing to outbreaks of religious violence.

During the 2011-2016 administration of President Thein Sein, a former general, military and civilian leaders, including so-called “reformists”, supported Ma Ba Tha through donations, protection and political backing.

Since seizing power in 2021, the military has continued to play the religion card.

In particular, two prominent monks have turned out to be junta favorites since the coup: SitaguSayadawAshinNyanissara and DhammadutaAshinChekinda.

AshinChekinda sprinkles scented water on a pennant-shaped vane for the Shwezigon Pagoda replica on July 12, 2022 in Moscow. / Venerable AshinNyanissara Facebook

SitaguSayadaw, 87, leads the ShweKyin sect, one of Myanmar’s nine Buddhist monastic sects. Prior to the 2021 coup, he was one of Myanmar’s most venerated and influential monks with hundreds of thousands of followers at home and abroad.

DhammadutaAshinChekinda built his reputation by creating Buddhist programs for teenagers during summer holidays, attracting hundreds of youngsters annually. He heads the International Theravada Buddhist Missionary University in Yangon and has tens of thousands of followers nationwide, including many in military circles.

Both monks have deepened their ties with coup leader Min Aung Hlaing since the 2021 takeover—perhaps unsurprisingly, in hindsight, given that they urged the military to seize power months ahead of the putsch. Both have drawn criticism for remaining tight-lipped about the junta’s atrocities.

In 2022, SitaguSayadaw praised junta leader Min Aung Hlaing as a “king” or “head of state” of “great generosity and wisdom” after the coup maker conferred Myanmar’s highest Buddhist title upon a former chairman of Ma Ba Tha. His praise of Min Aung Hlaing as a “king” came after thousands of people had already been killed in the regime’s crackdowns, raids and air and artillery strikes.

Another of Min Aung Hlaing’s staunchest robed supporters is U Kovida from eastern Shan State, widely known as VasipakeSayadaw, who is famous for his astrological forecasts and vows of silence. In fact, his practices are not related to Buddhism but to Hindu beliefs. The monk has been accused of advising the senior general to tell security forces to shoot protesters in the head during the early post-coup street demonstrations.

In return for backing the criminals in Naypyitaw, these monks have received donations, expensive vehicles, overseas trips, and high titles from the junta and cronies associated with the regime.

The regime’s close ties with SitaguSayadawAshinNyanissara and DhammadutaAshinChekinda were on full display when they accompanied regime leaders on an overseas trip to Russia to consecrate a replica of Shwezigon Pagoda in Moscow.

Exploiting a charitable nation

In 2013 and 2019, Myanmar was ranked near the top of an index gauging global generosity published by a UK charitable organization, with the Southeast Asian country’s deeply karmic mindset touted as a likely motivator for its benevolence.

This is partly a reflection of the strong influence of Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar; many adherents believe that what you do in this life will have consequences in the next, with monks playing a major role in the transmission of that belief.

A common topic of monks’ sermons is saṃsāra—a Pali and Sanskrit word meaning “wandering or running around in circles”, referring to the karmic cycle of life, death and rebirth into suffering in which Buddhists believe. Monks usually end their talks by stressing the importance of dana, or making donations.

Indeed, merit-making is among the most common and popular religious activities among Myanmar Buddhists. Most strive to adhere to the Five Precepts—to refrain from killing, stealing, engaging in sexual misconduct, lying and using intoxicants—and to accumulate good merit through donations, often to monks and pagodas, and performing good deeds to obtain a favorable rebirth.

Sadly, this generates a vast stream of revenue for influential monks like SitaguSayadaw, who has amassed a fleet of luxury cars including Mercedes, Lincolns and Bentleys, among other marques. While the extent of the overall “economy” surrounding monasteries in Myanmar—including not only the flashy vehicles and unusual wealth but also the regular public donations to temples and monasteries across the nation (which are massive, especially on festival days)—is not known, we can assume it runs into the hundreds millions of US dollars annually. The monks are making a fortune in Myanmar, almost half of whose 54 million people live below the poverty line.

Still, Myanmar’s Buddhist temples and monasteries remain busy and crowded, and the monks continue to thrive.

But criticism of their naked greed is growing.

When this publication’s Burmese edition published a story by Thai news outlet Khaosod about a Thai monk who accepted a donation of a BMW 750e priced at nearly 7 million baht (around US$200,000), Myanmar readers scoffed, claiming that monks in their home country would be unimpressed. One said, “Our Cele [celebrity] monks would laugh at [a BMW]…”

Another wrote: “Hmm this is not a Bentley. We have prosperous Buddhism, and your BMW is nothing here in Myanmar. Our monks have no desire—but they prefer to ride more expensive cars than Thais… We have no problem!!!” Any Myanmar person reading this would know that “our monks” refers to the “cele monks” like SitaguSayadaw.

It was not always thus. From colonial times until the previous regime in the early 2000s, the monkhood was a hotbed of political agitation in Myanmar.

How times have changed. Today, the monastic community is divided. Anti-regime monks are punished or marginalized, while those who actively promote nationalism, or simply remain neutral, are allowed to operate freely and prosper. In particular, the junta has proved adept at exploiting those monks with large followings.

Myanmar’s rich and powerful generals—who daily violate the precept against killing by overseeing the slaughter of civilians—regularly invite well-known abbots to their lavish residences, or visit their temples to shower them with grand donations. Some of the richest and most powerful figures in Myanmar have acquired their wealth within their own lifetimes. Is it because of past merit? At the same time, millions remain poor but continue to devoutly donate money or anything they can to monks and temples.

The monks who accept the Mercedes, Bentleys and latest-model smartphones seem to have no problem maintaining ties with the rich and powerful. Will these monks tell the generals to stop the slaughter?

One ray of hope that has emerged from all of this is the readiness of young Myanmar people, including progressive young monks, to question the behavior of Buddhist monks who audaciously and shamelessly show off their foreign cars, at a time when millions of their compatriots are sinking deeper into poverty.

Does it ever occur to these monks that such behavior might be inappropriate, let alone spiritually dubious, in a country ruled by a brutal junta whose forces engage in rape, bombing of civilian targets and the burning of homes?

Comfortable in their position between heaven and earth, Myanmar’s senior monks are making a killing.

Aung Zaw is a Burmese journalist.

This article was originally published onThe Irrawaddy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.