How Can Authoritarian Rulers Be Rolled Back? Accurate Information for Citizens Holds The Key

Suvojit Chattopadhyay | 06 January 2025

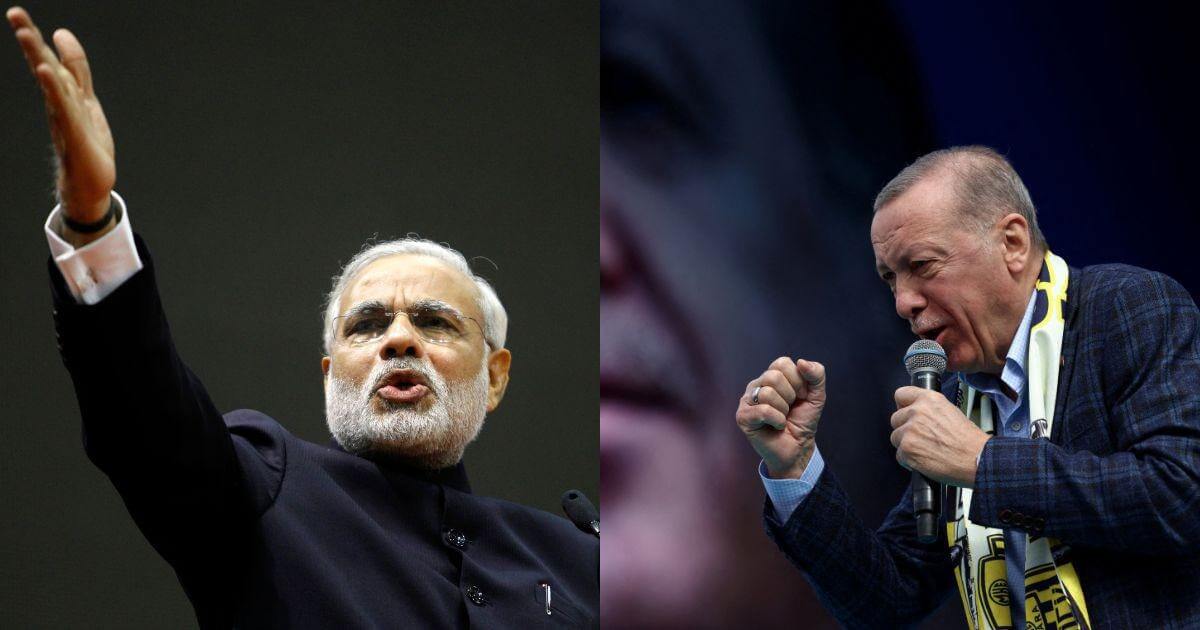

A study from Turkey found that support for democracy increased. But India’s fragmented media landscape and inconsistent Opposition are a challenge.

Everyday authoritarianism is made up of mundane acts of commission and omission. It manifests itself subtly through everyday practices rather than through dramatic, overt changes. Authoritarians attempt to normalise an environment where routine acts of the government gradually erode our freedom.

These acts include restricting free speech, using the law to restrict funding to civil society organisations and nonprofits, seizing or demolishing private property, curbing access to the internet, restrictions on what citizens can eat or drink and how they have sex.

Increasingly, the march towards authoritarianism has come to include a surfeit of narrative-building – that is, or propaganda – on the futility of democracy. This narrative often aims to undermine institutions of democracy that ensure a functioning system of checks and balances.

Notwithstanding the special discussion in Parliament on the 75 glorious years of the Indian Constitution, it is not uncommon to find members of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and their affiliates offer views that aim to destroy vital organs of democracy.

When anyone suggests that “too much democracy” is holding India back, as Amitabh Kant did when he was head of the government’s NITI Aayog think tank, it cannot merely be laughed off – it is essential to identify the deeper narrative that is being spun through such messages.

Narendra Modi has routinely deployed an array of instruments to attack the foundations of the constitutional republic.

He subverts almost every notion of federalism and ignores the constitutional framing of India as a union of states by routinely urging voters to pick the BJP both at the Central and state levels because a “double-engine sarkar” is more powerful.

His “one nation one election” plan to hold polls to the Lok Sabha and state assemblies simultaneously undermines the ability of citizens to hold the political class to account

He has demonstrated a blatant disregard for personal property rights with spectacular, freedom-destroying pronouncements such as demonetisation and by announcing a nationwide Covid-19 lockdown overnight.

Modi has weakened the finances of state governments through the constant implementation of “cesses and surcharges” that are collected by the Centre.

His government has blatantly weaponised the judiciary by promoting a culture of impunity among lower court judges and offering sinecures to retiring judges from higher courts.

All these are part of a wider narrative where the complex processes of a functioning democracy in a diverse country such as India are presented as inefficient and, therefore, dispensable.

Complementing this is an untiring party electoral machinery that plays a major role in guaranteeing success in election campaigns. Over time, repeated electoral success for a political party that is offering a watered-down version of democracy to citizens – one that is built around majoritarian appeasement and the image of a muscular government – can make it appear futile to fight for change.

India is perhaps not there yet, but we are undeniably on a particularly slippery slope.

What drives citizens to demand democracy under authoritarian regimes? A new CEPR paper featured in VoxDev, titled“Misperceptions and Demand for Democracy under Authoritarianism” examines this question through a large field study in Turkey. The authors explore how correcting citizens’ misperceptions about democratic institutions by providing accurate information could encourage greater public demand for democratic governance.

The authors studied an intervention that came against the backdrop of the devastating 2023 earthquake in Turkey, where the loss of life and property was compounded by the serious shortcomings in governance. This was made worse by corruption and weak institutions.

Through an online experiment and a large-scale field campaign where a total of 880,000 voters were included, about half the sample was exposed to information packages that linked data on the state of Turkey’s institutions (such as international surveys that pointed to decline in media independence) with corruption. The messaging was factual, simple and framed in evocative terms.

The survey in their online experiment captured the initial attitudes of supporters of various political parties towards democratic institutions. This provided a foundation for interpreting the results from the experiment.

The results were striking. Voters exposed to accurate information about democratic institutions and media independence reevaluated their beliefs about the health of democratic institutions. This shift was particularly pronounced among those who had previously underestimated the extent of institutional decay and supported the incumbent government.

The opposition vote shares in this cohort increased by as much as 4.4% . The effects were found to have endured into the 2024 municipal elections in Turkey. On the basis of this finding, the authors suggest that accurate information can sway voters sufficiently to alter even their long-term allegiances and voting patterns.

In this study, there are two further takeaways: first, a significant portion of government supporters accepted the informational treatments to be credible. Second, those with greater misconceptions about the state of democratic institutions in Turkey were more influenced by these treatments.

These suggest that support for authoritarian regimes is highly dependent on misinformation and propaganda and does not necessarily reflect apathy toward democracy.

Turkey is not as different from India as we would like to imagine. Writing in 2014, author Amitav Ghosh had shown how the victory of Recep Tayyip Erdogan in presidential elections in Turkey in 2003 marked a shift from the country’s dominant secular-nationalist order to a regime led by a strongman that appealed to majoritarian religious sentiments.

What has been visible in Turkey over the last two decades is a steady erosion of democracy, gradually at first, and then rapidly.

What lessons do this hold for us in India? In India too, the campaign to sabotage democracy in ways that would retain all but the performative act of voting is well and truly underway. The beleaguered Opposition needs to contest the BJP’s narrative.

The CEPR paper highlights the importance of targeted informational campaigns that would have to be delivered through appropriate channels. It emphasises the importance of media independence and the indispensability of sophisticated and relentless media (including social media) campaigns by political parties looking to challenge the BJP.

An inconsistent, ad-hoc approach to political mobilisation on the ground and disparate media campaigns – as is the case now – is unlikely to bear fruit.

Suvojit Chattopadhyay works on governance and public policy in South Asia and East Africa.

This article was originally published on scroll Inn.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.