Trump’s Approach to Southasia Bolsters China’s Regional Sway

AmanthaPerera | 18 March 2025

The Trump administration’s foreign-aid freeze, tariffs and deportations threaten the United States’ established position and popular goodwill across Southasia, and China stands ready to step further in

IT HAD BEEN four years since Myanmar’s military junta seized power in a violent coup executed on 1 February 2021. Yet the day marking the coup in 2025 passed with hardly a blip on the international news tickers. Instead, the news was dominated by the latest tariff proclamations coming out of Washington DC, targeting Canada, China and Mexico. Four years on, Myanmar has fallen off the global attention spectrum as dramatically as it had claimed it when the coup was first launched.

A decade earlier, too, Myanmar was especially in the global limelight. In November 2014, US president Barack Obama arrived in Myanmar to talk democracy. To many in the country, then in the early years of an attempted transition to democracy, it seemed the final break from decades of brutal military rule. “Today, I say to you – and I say to everybody that can hear my voice – that the United States of America is with you, including those who have been forgotten, those who are dispossessed, those who are ostracized, those who are poor,” Obama pledged at the University of Yangon.

“Yangon, that day when Obama visited first, was like it was getting ready for an epoch-making event,” a Myanmar national who had daily interactions with the US mission during the Obama visit said. In 2014, US assistance to Myanmar reached USD 150 million. The Myanmar national said it had felt like the United States had matched the verbal bravado with action and was invested in Myanmar’s future. He, like so many in Myanmar, trusted the United States’s word. That turned out to be a mistake.

As Donald Trump, the newly installed president of the United States, has deployed his policy of “America First”, with no concern for anything that he sees as incompatible with narrow-minded US interest, the old promises to Myanmar have been thrown by the wayside. Take, for instance, Trump’s recent executive order freezing US foreign aid. In the 12 months up to October 2024, under the preceding US administration led by Joe Biden, the United States spent nearly USD 141 million to assist Myanmar’s “crisis-affected communities facing armed conflict, displacement, and growing food insecurity.” Now, the future of all of that support is under question. By mid-February, the community of exiled Myanmar media working from exile in the Thai border town of Mae-Sot was reeling. The Irrawaddy, a popular news outlet, was dependent on US funding for some 35 percent of its budget via media support from the non-profit group Internews.

“The Americans just forgot about us,” said a journalist and activist from Myanmar who was forced into exile following the 2021 coup. The fear, he told me, is that Myanmar is unlikely to be a priority for the US under Trump.

Myanmar exemplifies how the volatility of US policy can have drastic consequences across the world, including in Southasia. Myanmar is hardly the only country in the region to be hit hard by Trump’s new policies, going beyond just the suspension of aid. When it comes to the Trump administration, “if you just look at it in terms of the list of things to tackle right away, I think Southasia does not come at the top of that now,” Rohan Venkat, the managing editor at the University of Pennsylvania’s the Centre for Advanced Study of India, said. That is opening up opportunities for other players, especially China, to make gains in Southasia as countries re-evaluate their earlier relationships with and reliance on the United States.

At a recent forum on the shifting situation in Myanmar, hosted by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand, speakers emphasised two significant factors – the diminishing role of the United States in global geopolitics, counterbalanced by the global rise of China.

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS working in the region have confirmed that, after Trump took office, all projects reliant on US government funds have been suspended for at least 90 days. During that period, these projects are to be reassessed to determine whether they “align with the new administration’s policies”, a source from an international agency in contact with US State Department officials said. Most agencies have informed their partners that the suspension is likely to remain in place for six months and to expect major overhauls.

In Sri Lanka, the non-profit sector is in a tailspin, with even many who held permanent jobs informed that their employment would cease – some as early as 1 February. Sources from the non-profit sector said between 1000 to 1500 jobs were at stake. The non-profit Women in Need said that its crisis centre in Ratnapura, in south-central Sri Lanka, might have to shut down entirely. Sri Lanka’s government is also impacted, with at least four ministries affected by the freeze. At least a third of USAID’s budget in Sri Lanka was earlier going into government projects.

In Nepal, the freeze has impacted projects in health, agriculture, education and inclusive policy, with a five-year agreement amounting to USD 659 million in limbo. More recently, disbursements under the Millennium Challenge Compact, a bilateral US foreign-aid agency, have been suspended, which look certain to cause delays in completing projects in Nepal related to electricity transmission and road development. Across Afghanistan, around 50 national and international aid organisations have had their operations partially or completely suspended. Projects related to polio and measles vaccination, as well as education for Afghan girls in defiance of Taliban guidelines against this, are also impacted. In Pakistan, projects related to post-flood repair, education, domestic violence, legal aid and climate change have been suspended.

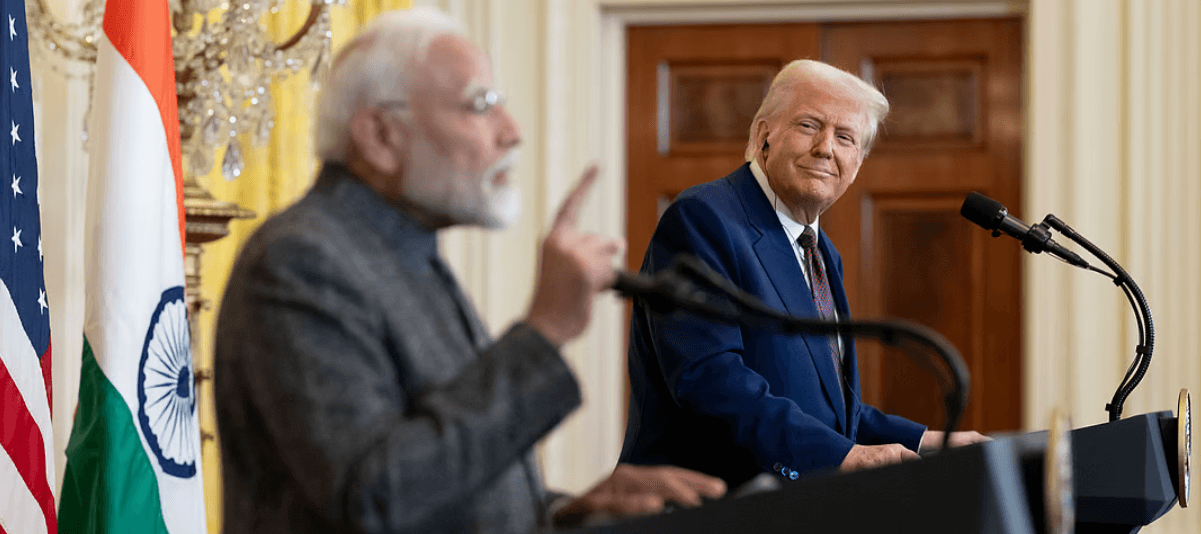

In India, Trump’s return to the White House is likely to embolden the entrenched Narendra Modi regime. During a recent visit to Washington DC, the Indian prime minister received a warm welcome, with Trump calling him a “great friend”. In a phone call before the visit, Trump also said India would “do what’s right” on undocumented immigrants in the United States, who are now being deported in droves to their countries of origin, including India. When reports emerged of Indian deportees being shackled on their return flights home, there was public outrage – but the response from the Indian government was muted, with the external affairs minister, S Jaishankar, telling parliament that the Indian administration was working to ensure that people deported were not being mistreated. Still, such mass deportations risk eroding public goodwill for the United States – including in Southasian countries beyond India, with many due to receive deported migrants from the United States.

Beijing has shown in the past that it is willing to step into the void created by the United States and its allies. It did so in Sri Lanka after the end of the country’s civil war, for instance, as the country struggled to attract international investment and goodwill primarily due to allegations of human-rights abuses by government forces during the last phase of the fighting. Similar Chinese overtures, whether through investment or aid, have also proven successful in Nepal, the Maldives and Pakistan – much to the chagrin of New Delhi.

To compound the situation, Trump has also withdrawn the United States from the Paris Climate Accord and signalled a radical departure from the US’s earlier involvement in global efforts to mitigate the climate crisis. With the United States withdrawing from climate finance, China has further opportunity to gain a foothold in many Southasian countries where such finance was expected.

More financial shocks are in store for Southasia from Trump’s trade and tariff policies. Trump has already demonstrated that tariffs will be one of his main weapons, and these carry the potential to upend the current global system of trade.

“The question mark is the one of trade,” Venkat said, adding that disruptions in global trade and a rise in prices can potentially be problematic for the region. “We are already dealing with a world where growth is subdued, where inflation has taken down lots of leaders. We are also dealing with a region that has faced tremendous upheaval politically post COVID.”

In 2024, South and Central Asia enjoyed a positive trade balance of USD 63 billion with the United States. India’s exports to the United States that year were valued at just over USD 87 billion, while imports were a fraction below half of that, at USD 41 billion. For Sri Lanka, it was even starker, with exports of USD 3 billion, and imports worth around a tenth of that. In terms of tariffs, there is hardly any manoeuvring space for the region, as it continues to rely on the United States as an export market. Meanwhile, the United States is in the process of reviewing trade agreements and is expected to try to mitigate its trade deficit with Southasia.

Such a weak negotiating position vis-a-vis the United States strengthens what China can offer Southasia as an alternative market and alternative global power – and its prominence as a lender across much of the region only adds to its sway. China is already setting the stage for this.

Since September 2024, Myanmar’s ruling junta has indicated that it is contemplating holding elections this year, despite being in control of less than half the country as numerous armed groups continue to fight against it. There is growing groundswell against elections under the present regime – which are widely seen as a way of legitimising the junta’s control. In whatever happens next, Beijing’s role is crucial.

Beijing has indicated that it is supportive of polls, and it holds sway over at least some of the armed groups that have been battling Myanmar’s junta. While China initially appeared supportive of these armed groups, that support waned as fighting approached its borders and its business interests came under threat. Thanks to intervention from China, many of these armed groups, including the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, have agreed to a ceasefire – cementing China’s influence in the country.

As in Myanmar, China has already made inroads in Afghanistan. While the United States and the West, like much of the rest of the world, have continued to ostracise the ruling Taliban regime that took power after the US’s withdrawal from the country in 2021, China has officially received an ambassador from Kabul, paving the way for a potentially deeper relationship.

Even in New Delhi, after years of India’s hostile outlook on China as a major rival, there are rumblings of a rapprochement with Beijing driven at least in part by the potential need for greater bilateral trade cooperation given the uncertainty over US tariffs. China is already India’s main source of imports, giving it great leverage over New Delhi. If the Modi government’s present bonhomie with the Trump administration should sour for any reason, or if tariffs cut the United States off as a major Indian import market, China’s position will only strengthen further.

There is already a joke on the streets of Beijing that Trump could end up making China great in pursuing his promise to “Make America Great Again”. In South asia, certainly, that could well become the case. △

Amantha Perera is a journalism academic, researcher and writer based in Australia.

This article was originally published on Himal.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.