37 Years and Counting: Why Has Myanmar’s Democracy Struggle Taken So Long?

Kyaw Zwa Moe | 07 July 2025

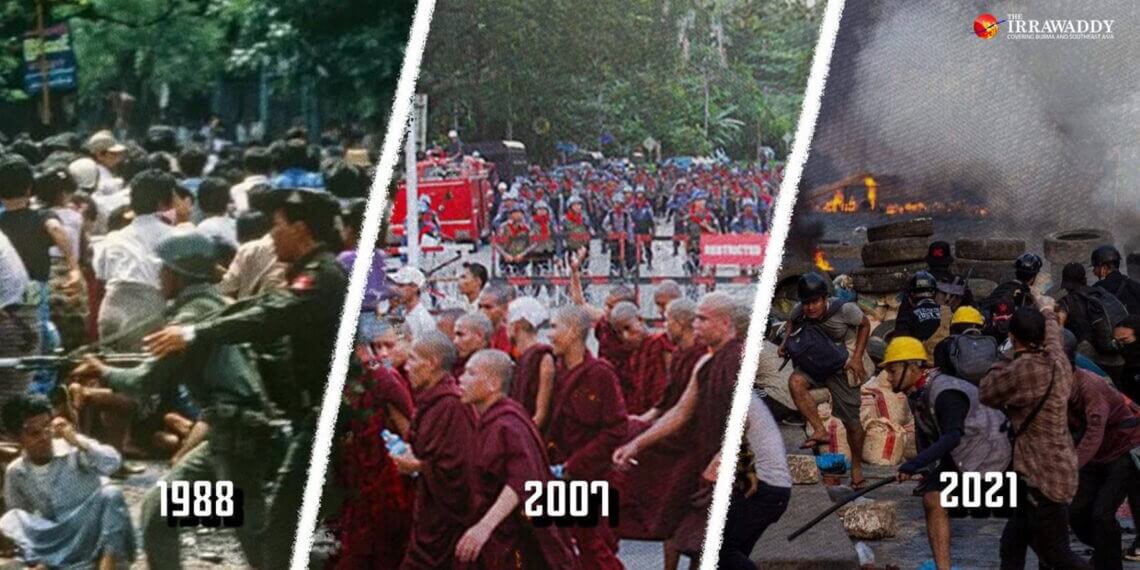

It has been 37 years since the 1988 Democracy Uprising. For more than three decades, the people of Myanmar have been fighting to restore the democracy stolen from them by military dictators. And yet, after all this time, true democracy remains out of reach.

Why has it taken this long?

To find the answer, we must examine the different methods the people of Myanmar have used in their struggle—and why these efforts have so often been thwarted.

Achieving democracy is never easy. There is no fixed formula, no guaranteed roadmap. Various strategies have been applied in different countries around the world—some succeed, some fail, and some remain in limbo. In Myanmar’s case, the situation hasn’t just stagnated—we’ve been forced backwards.

Let’s explore the different paths that have been taken or proposed in Myanmar’s long, painful struggle for democracy.

Non-violent uprisings

The first significant popular uprising that sought to bring about democracy in our country occurred in 1988, though there had been occasional protests against authoritarian rule since the coup in 1962. It was a people-powered revolt—a non-violent mass uprising that started among students and spread nationwide.

From August 8 to September 18, millions of people took to the streets, calling for democracy. It was a defining moment: the one-party authoritarian regime that had ruled for decades collapsed. Military dictator Ne Win stepped down. His Burma Socialist Programme Party was dissolved.

But it wasn’t the end of authoritarian rule. Ne Win handed power to two loyalists, U Sein Lwin and Dr. Maung Maung, who tried soft tactics to placate the public. The people saw through it. They continued protesting until both presidents were forced out within weeks.

When appeasement failed, the military resorted to violence once again and seized power.

This pattern repeated in 2021, during the Spring Revolution. After another military coup, the people rose up—only to be met with brutal suppression. Nearly five years on, the military continues to attack civilians.

Despite their historic power globally, mass uprisings have never led to real democratic transition in Myanmar. Why? Because the generals refuse to recognize the will of the people. They respond to peaceful protest with bloodshed.

But mass uprisings have succeeded elsewhere. In 1989, a year after Myanmar’s uprising, Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution toppled four decades of communist rule in just one week—because the regime negotiated the peaceful transfer of power.

In the Philippines in 1986, the People Power Revolution succeeded in forcing dictator Ferdinand Marcos to step down. The country has remained on a democratic path—albeit a fragile one—ever since.

Comparing these countries to Myanmar, while they all endured dictatorships, we can see that our country’s generals have shown an exceptionally stubborn and reckless disregard for the people’s will.

Elections

One tangible result of the 1988 uprising was that the military was pressured into holding multi-party elections. The 1990 election saw a sweeping win for pro-democracy forces.

But the military refused to accept the results, and the vote was nullified.

Three decades later, the same playbook was used. After another landslide victory for democratic parties in the 2020 election, the military once again seized power and voided the result.

Elections—a core pillar of democracy—have never been respected by the generals in Myanmar.

Indonesia, on the other hand, offers a contrast. In 1999, democratic elections helped transition the country away from military dominance. By 2004, Indonesia had fully removed the military from political power.

The difference? In Indonesia, a culture of respect for democracy took hold. In Myanmar, the generals have never embraced such a culture. Despite the people’s repeated efforts, the generals have twice erased free and fair elections.

The reason is that while the Myanmar people have developed a democratic political culture, the generals have never embraced it.

If the 1988 mass uprising and the 1990 election results had truly opened the path to a democratic system, our country would have been a democracy for over 30 years by now.

International carrot and stick

The international community—especially democratic nations—has long sought to influence Myanmar’s trajectory using a mix of pressure and engagement.

After the 1988 coup and violent crackdown, the US suspended diplomatic ties and economic aid. Additional sanctions followed as the junta continued to imprison pro-democracy activists, ignore election results and abuse human rights.

Under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, new investments were blocked and visa bans for the generals were imposed. The EU applied similar measures. When the junta crushed the 2007 Saffron Revolution, further penalties were added.

But the military leaders remained unmoved.

Meanwhile, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has always opted for a “constructive engagement” strategy, sticking to its traditional non-interference policy, under which members refrain from criticism. This approach has not only failed—it has arguably emboldened the generals over the decades. ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar adopted in 2021 has also proven toothless.

Eventually, in the late 2000s, by which time the political situation had been stalled for years, even Western nations began to doubt the effectiveness of sanctions. After a period of political opening began under Thein Sein in 2011, engagement replaced pressure. Aid flowed in and political progress seemed possible.

But when faced with the risk of losing power, the generals reverted to form. The 2021 coup proved they valued control over reform, even if it meant destroying national progress.

In short: neither sanctions nor engagement worked to really change the mindset and attitude of the generals. Because Myanmar’s generals play by their own rules.

Foreign military intervention

International military intervention, often discussed in the context of R2P (Responsibility to Protect)—the principle that the international community has a responsibility to intervene when a state fails to protect its population from atrocities—has also been called for in support of Myanmar’s democracy cause.

Such calls were particularly strong during the period after Cyclone Nargis in 2008 and in the early phase of the 2021 Spring Revolution.

However, such interventions have never materialized.

The main reason is that the international community views Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement as merely an internal political conflict.

Another factor is geopolitics.

Major world powers including the US don’t want to deal with the possible increase in geopolitical tensions that would result from military intervention in Myanmar, a country located in Southeast Asia bordering China.

Another point is that to Western countries, Myanmar’s democracy is not important enough to warrant military intervention. US officials have stated they are not considering any such move.

Whatever the case, while international forces were able to overthrow dictators in Iraq and Afghanistan, we’ve also seen that they were not successful in establishing democracies there.

Buddhist dhamma

In addition to seeking various international approaches, Myanmar has also applied its own traditional Buddhist dhamma methods. Throughout successive eras of political struggle, there have been many monks who stood with the people.

However, nowadays, not only are there many generals who worship monks, but there are also many monks who worship generals—despite the fact that they commit the five grave sins in Buddhism, including killing.

Of course, there have been monks who have supported the cause of democracy. On August 8, 1990, at an alms-offering ceremony in Mandalay to mark the second anniversary of the ’88 democracy uprising, the military harassed, blocked and beat the monks.

Due to this incident, a boycott called Pattanikujjana (refusing alms from the military) began among the monks. The military regime ordered its troops to raid monasteries in Mandalay and Yangon, arresting and imprisoning hundreds of monks, including senior abbots. However, the monks did not withdraw their boycott.

In 2007, when the military government suddenly raised fuel prices, commodity prices also increased. Because this affected people’s livelihoods, the monks stood with the people and took to the streets in peaceful marching meditation, sending loving-kindness.

However, even this loving-kindness was met with bullets. Senior General Than Shwe’s military regime at that time beat, arrested, gunned down and imprisoned monks as they marched and chanted peacefully.

Not even the dhamma can move the generals’ hearts, it seems.

Change within the military

Another example of wishful thinking is the idea that new generation officers within the military would stand with the people and oppose their generals. This is something that some people, including scholars, researchers, diplomats and some leaders have entertained over the past decades.

Currently, while the military is suffering from defections, we haven’t seen conditions that would lead to internal military changes or revolts. In fact, the usual pattern is that younger generals who rise to power in the current system are even worse than their predecessors. It shows how systematically the military brainwashes its new recruits.

If we compare Ne Win, Than Shwe and current military leader Min Aung Hlaing, we can see this clearly. The generals have only grown more extreme. If there were people within the military who wanted real change, Min Aung Hlaing would have been gone long ago.

Armed revolution

Armed struggle is not at all a new method in Myanmar. Since independence in 1948, political groups and ethnic armed organizations that disagreed with or distrusted the government’s political path have had a tradition of armed resistance.

The same was true after the 1962 military coup, which forced some dissidents to take up arms on the border areas. After the 1988 coup, the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF), a student army formed to fight for democracy, emerged. This was armed struggle for democracy.

As usual, armed revolution is the last resort. However, it must be said that non-violent political approaches dominated Myanmar politics in the post-’88 period. The struggle for democracy was waged using the non-violent political methods mentioned above.

The armed struggle for democracy that emerged from 1988 didn’t go as far as expected. But the armed revolution that emerged after the 2021 coup involved not only young people from cities like Yangon and Mandalay, but also many ethnic youths from cities in ethnic states, who joined the fight.

The 2021 armed revolution, initiated by Gen Z youth and later led by well-established ethnic armed groups, achieved many successes in nationwide offensive operations in 2023 and 2024. However, China’s move to side with the military regime and pressure ethnic groups to stop fighting it has indeed slowed the momentum of the Spring Revolution.

Looking at this point, when international communities or neighboring countries intervene on the wrong side, it truly delays the cause of democracy.

All methods exhausted?

Pro-democracy groups and the people of Myanmar have tried or proposed all these methods. So the question is whether Myanmar’s democratic methods have been exhausted.

The military generals respond to neither soft nor hard approaches—neither carrots nor sticks work, neither diplomatic nor moral methods alone are effective. That’s why the people have turned to their last resort—armed struggle.

In truth, all these methods are useful to some extent. Each method has its own effectiveness. People’s participation, international action, cutting off fuel supplies to the military council and so on—these methods are crucial factors for democratic success.

This is a battle between dictators and the people. Even the United States, which is seen as an established democracy, is struggling to preserve democracy today, as we can see.

Whatever happens, my thoughts on our country’s unfinished democratic struggle are: “As long as there’s struggle, there’s hope.”

No matter how long it takes, the struggle for democracy will certainly continue until victory.

Kyaw Zwa Moe, Executive Editor of the Irrawaddy.

This article was originally published on The Irrawaddy

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.