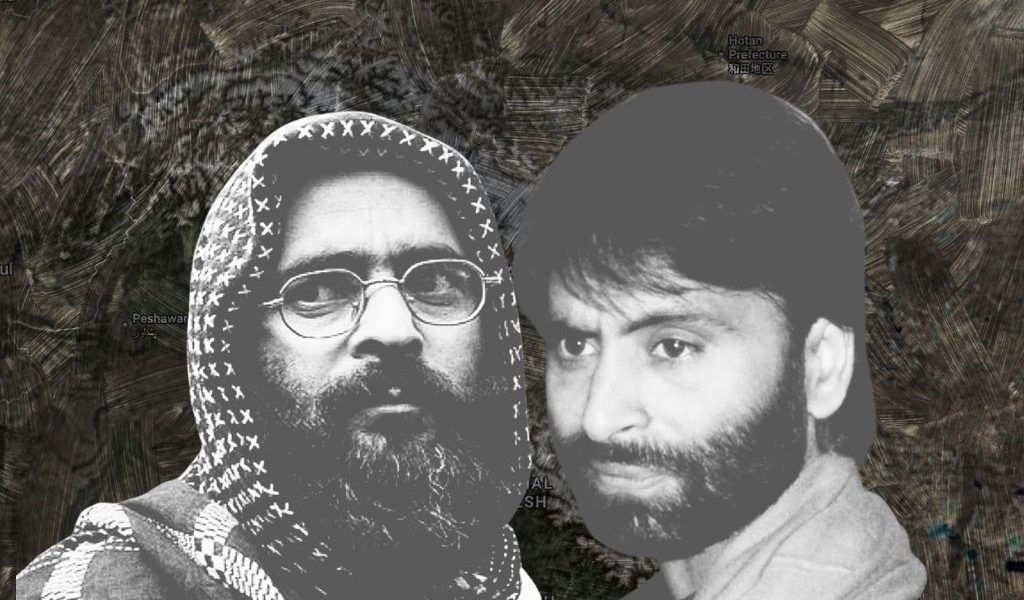

Betrayed: The Tragedy of Two Kashmiris and the Crisis of Indian Justice

Until we acknowledge the wrongs done to Yasin Malik and Afzal Guru not as Kashmiri grievances, but as Indian failures, we will remain a country afraid of the mirror it refuses to face.

Mehbooba Mufti | 29 September 2025

Two men. Two decades apart. One consistent betrayal.

In the long, tormented ledger of India’s relationship with Kashmir, few stories reveal the depth of institutional duplicity as starkly as those of Afzal Guru and Yasin Malik. Separated by time, context, and ideology, both men now stand united not only in memory, but in what their cases expose: how the Indian state has used individuals to serve short term goals and then discarded or punished them once they outlived their usefulness.

A scapegoat hanged in silence

Afzal Guru, convicted in the 2001 parliament attack, was executed in 2013. His hanging was carried out in secret. His family was not informed in time. His body was buried within the walls of Tihar Jail far from home, and far from justice.

But Afzal had, years earlier, written a letter. In it, he named Davinder Singh, a senior officer in the Special Task Force, claiming that Singh had coerced him into helping the very people later accused of the parliament attack. According to Afzal, Singh instructed him to escort one of the men later shot down at Parliament House to Delhi, find him a place to stay, and arrange a vehicle. In fact, Afzal had said this in open court during the trial, which statement is on record. Afzal was a surrendered militant, who had consciously rejected militancy to return to the Indian fold but claimed that he was repeatedly picked up and taken to the STF Camp to be tortured for days on end. At one such stint, he was contacted by Davinder inside the STF camp and assigned a job as aforesaid.

These explosive allegations were never seriously investigated.

And then came the twist, in 2020, Davinder Singh was arrested while transporting militants in Kashmir. A man named by a condemned prisoner years earlier was caught red handed in almost the same crime. Yet there was no re examination of Afzal’s case, no reopening of the file, no reckoning.

Afzal was branded a terrorist. Singh was quietly sidelined. One was executed and the other, protected.

What does it say about our justice system when a man names a police officer who is later arrested for terrorism and yet, it is the whistleblower who is hanged, while the officer remains shielded?

From peace envoy to prisoner

Yasin Malik, once a militant, renounced violence in 1994 and committed himself to political dialogue. For more than two decades, he was embraced by the very state that would later condemn him.

He engaged in dialogue with governments under different prime ministers right from P. V. Narasimha Rao and Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Manmohan Singh. He held extensive talks with intelligence officials, National Security Advisors, and even Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh leaders. In 2006, he says he was asked by Indian intelligence agencies to meet Hafiz Saeed in Pakistan to urge a shift from violence to dialogue. After that meeting, he returned and briefed India’s top leadership, who, he claims, thanked him.

Those very same interactions are now being used as evidence to imprison him for life under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). In 2022, Malik was convicted not for waging war, but for the same peace outreach the state once facilitated.

When the state invites you to be part of the peace process, then locks you up for doing it what hope is left for dialogue?

Two lives, one pattern

Afzal Guru’s letter and Yasin Malik’s affidavit are not isolated grievances. They reveal a disturbing pattern of a state that uses coercion when it suits (Afzal Guru), promotes diplomacy when convenient (Yasin Malik), and discards both when the political winds change.

In Afzal Guru’s case, the justice system refused to investigate his claims, and executed him to satisfy the “collective conscience of the country” and also the political need for closure. In Yasin Malik’s case, the state turned peace-building into a crime, rewriting history to frame him as a terrorist rather than a negotiator.

This is not about absolving either man of past associations or actions. It is about demanding consistency, transparency and truth. A democratic society cannot function when truth is conditional, justice is selective, and peace is punished.

If whistleblowers are executed, if peace-builders are imprisoned, if trust is betrayed over and over again, then what future remains for reconciliation in Kashmir?

This is not just about two men, it is about how we, as a nation, choose to confront our past and whether we’re willing to learn from it.

Do we want peace or permanent punishment? Do we seek truth or only what is politically convenient? If we can hang Afzal without investigating the man he named, and if we can jail Yasin for doing the outreach we once asked of him, then we are not just betraying Kashmir, we are betraying ourselves.

A.S. Dulat, the then chief of the Research and Analysis Wing, and the present national security advisor Ajit Doval need to speak up since they were the ones who played a very important role in engaging Yasin Malik.

Until we acknowledge these wrongs not as Kashmiri grievances, but as Indian failures, we will remain a country afraid of the mirror it refuses to face.

Mehbooba Mufti is the leader of the Jammu and Kashmir People’s Democratic Party (PDP), who served as the last chief minister of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

This article was originally published on The Wire.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.