China’s Bullying Diplomacy: How Beijing Sabotaged Myanmar’s Revolution

Kyaw Zwa Moe | 28 November 2025

Many people within Myanmar’s revolutionary movement—like much of the population in general—believe that if China hadn’t intervened following the launch of the anti-regime military offensive Operation 1027 in 2024, the resistance would be besieging the junta’s nerve center Naypyitaw by now. In other words, that the Spring Revolution might already be nearing victory.

China often speaks of its “pauk-phaw,” or “brotherly,” relations with Myanmar. But the question remains: does this brotherhood apply to the Myanmar people—or merely to the rulers in Beijing and Naypyitaw?

The second wave of Operation 1027, launched in June 2024 by the Brotherhood Alliance—comprising the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and Arakan Army (AA)—together with the People’s Defense Force, was unprecedented in scale and success. After capturing Lashio, the capital of northern Shan State, the alliance was preparing to advance further.

For the first time since the 2021 coup, the revolutionary dream felt within reach. Many imagined that the alliance could seize Pyin Oo Lwin—the town often referred to as the “West Point” of Myanmar because it is home to the country’s top military academy—and even Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city. If that had happened, Naypyitaw, the junta’s nerve center, might soon have been surrounded.

The regime was crumbling. Six brigadier generals had been captured, countless troops surrendered, and the Northeastern Command itself had fallen. The once-mighty Myanmar military was demoralized and directionless.

And at that precise moment, a savior emerged for the regime—China.

China’s bullying diplomacy

At the height of Operation 1027’s momentum, Beijing pressured the resistance forces into ceasefire talks—at the junta’s request. After Lashio fell, that pressure intensified. Declaring that “the military is the most important element in Myanmar’s politics,” China issued a threat in August 2024: If the fighting didn’t stop, it would cut off all support—applying its version of the “four-cuts” anti-insurgency strategy long practiced the Myanmar military itself.

Under this coercion, the MNDAA (aka the Kokang Group) halted its advance toward Mandalay and Taunggyi, and even announced it would not engage with Western governments or Myanmar’s parallel National Union Government (NUG). Then, in April 2025, in a move orchestrated by China, the MNDAA handed Lashio back to the regime. The Myanmar military reclaimed the city without firing a single shot.

By July, the TNLA too was forced to withdraw from Nawnghkio after facing China’s “four-cuts” pressure. Thanks to Beijing, the junta has been able to reclaim territories that resistance forces had liberated at the cost of their lives. And again, this month, with Beijing’s intervention, the ethnic army agreed to return the liberated towns of Mogoke in Mandalay Region and Mongmit in northern Shan State to the regime as part of a ceasefire agreement.

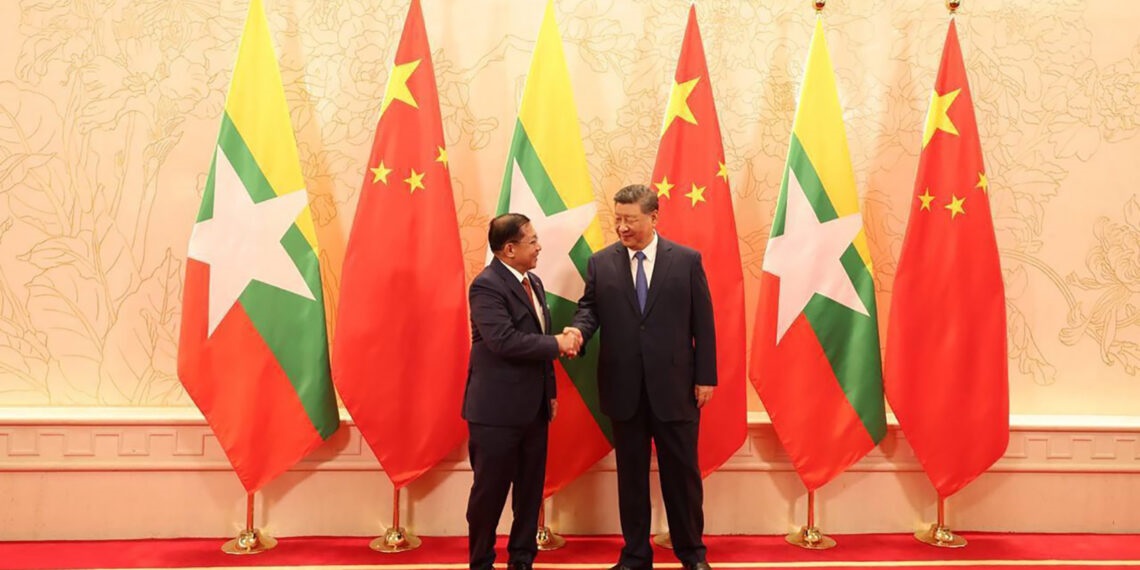

This is what I refer to as China’s “bullying diplomacy”—a policy of coercion and control that props up Min Aung Hlaing’s regime while undermining Myanmar’s revolutionary forces. Unsurprisingly, during a visit to China, the junta chief personally thanked President Xi Jinping for this “support.”

China’s political maneuvering

In the aftermath of the 2021 coup, and throughout 2022 and 2023, China did not openly endorse or recognize Min Aung Hlaing’s leadership. It kept its distance. Even when the Brotherhood Alliance, which maintains close ties with China, launched the Operation 1027 offensive, Beijing didn’t intervene—partly because of those groups’ vow to crack down on border telecom fraud operations.

At that time, even the country’s strong ethnic armed group, the United Wa State Army (UWSA), was providing military and financial support to the revolutionary forces. Recently, however, under Chinese pressure, it said that it would no longer provide any such assistance.

China’s silence when Operation 1027 was launched effectively signaled its permission to strike the Myanmar military. In other words, China gave a green light to the ethnic armed organizations to proceed.

From another perspective, that silence meant China implicitly opposed Min Aung Hlaing’s regime, and refused to give it legitimacy. At the United Nations, China didn’t object to the decision to keep U Kyaw Moe Tun, who publicly opposes military rule, as Myanmar’s ambassador to the world body.

These moves reminded us of China’s earlier support for the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), which fought General Ne Win’s government.

As everyone knows, China is an authoritarian communist country. During Mao’s era, it provided extensive assistance to brotherly communist parties, seeking to export revolution. That’s why they supported the CPB, which shared their political ideology. However, after Mao died in 1976, and reformist Deng Xiaoping became leader of the Chinese Communist Party, China’s policy toward Myanmar changed.

Starting in 1980, they stopped supporting the CPB. From that time, China began engaging more directly with the Myanmar government, adopting a policy of not supporting groups opposing it.

Since then, China has consistently provided political support and protection to successive Myanmar military governments, and has also been a major trading partner and supplier of military hardware. In effect, China has helped prolong military rule. Looking back over the past five decades, it’s clear that China has never pursued a policy that genuinely aligns with the interests of the Myanmar people. It only cares about its own interests.

However, after 2021, following the military coup, China’s stance toward military leader Min Aung Hlaing’s regime was interesting, as mentioned earlier.

To analyze it politically, China was apparently not happy with the military’s ouster of the democratically elected civilian government. Nor did it seem to approve of the arrest of elected leaders such as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President U Win Myint, and other members of the civilian administration.

Reports even surfaced that Chinese officials had requested permission to meet with detained Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. That request, however, was denied.

It might seem odd that authoritarian communist China would support Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government, which was ideologically closer to the West.

‘Complicated love’

Why would an authoritarian communist leader take a liking to a democratic leader? To understand this “complicated love”—a relationship based on different ideologies, opposing political standards, and complex interests—we need to understand three key points.

For China, one of the things it values most in Myanmar is stability, which allows it to pursue its economic ambitions there without disruption.

The first point is that the 2021 coup threw Myanmar into complete chaos, both politically and economically. As a result, Xi didn’t seem to like Min Aung Hlaing.

Second, Xi’s liking for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is believed to stem precisely from the fact that her government was democratically elected, which could guarantee the stability China wants. Her government enjoyed strong public support, so doing business with it was safe for China. The advantage is that anti-China sentiment and public resistance to Chinese projects could be kept relatively low.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said: “China is our neighbor and whether we like it or not we are going to be neighbors forever.”

Third, although Daw Aung Suu Kyi’s government maintained close ties with the West and received Western support, it also adopted a practical and constructive approach toward China.

In managing Chinese projects, it made efforts to ensure due process. For example, the Kyaukphyu project, which was approved during the Than Shwe regime and Thein Sein administration. The project, part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was originally agreed to by previous governments at a cost to Myanmar of US$10 billion. If it had proceeded as planned, Myanmar would have fallen into China’s debt trap, so in 2018, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi renegotiated with China and was able to revise the contract to $1.2 billion.

In practice, it seemed more convenient for China to work with Myanmar during Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s time.

Xi himself visited Myanmar in January 2020 and was able to sign agreements related to the BRI.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi visited China in 2016, 2017 and 2019, and Xi received and met with her each time.

Chinese President Xi Jinping shakes hands with Myanmar State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on April 24, 2019. / AFP

It would definitely have been easier for Xi to advance his BRI in Myanmar—a country which holds strategic geopolitical importance for China—while its political landscape was stable and bilateral ties were good.

So, in the early years of Min Aung Hlaing’s coup, China neither supported him nor blocked opposition forces—it was a kind of green light for the resistance.

Later, China’s special envoy met with former Senior General Than Shwe and former President Thein Sein, who are Min Aung Hlaing’s mentors. China was probably trying to sound out what they could do to help alleviate the situation. China even invited Thein Sein to Beijing.

After that, China’s political position began to shift.

Shift to authoritarian solidarity

Eventually, pragmatic ties with the junta—which, while illegitimate, held the power—and economic incentives prevailed over principles. In time, China adjusted to reality, recognizing that Min Aung Hlaing remained in power and that its economic interests required access to Myanmar’s resources and protection of Chinese investments. Beijing decided to align with the junta and exert pressure on ethnic armed groups instead.

Min Aung Hlaing also offered many economic incentives while visiting China. In exchange for Beijing’s support, he promised access to all natural resources, including rare earth minerals, and anything else China wanted. This time, there will not be any due process, as was present during the civilian government era.

It seems that former military intelligence officers worked hard to influence China’s policy shift in favor of Min Aung Hlaing.

Before both of Min Aung Hlaing’s trips to China, former intelligence officers Brigadier General Thein Swe and Colonel Hla Min visited China ahead of him and met with Chinese think-tanks. The duo operated under the little-known Paragon Institute. These former spies likely used Chinese think-tanks to lobby the Chinese government on behalf of the junta. (Thein Swe and Hla Min were once close aides to former military intelligence chief General Khin Nyunt, who was responsible for mass arrests, torture and killings of pro-democracy activists.)

Sinophobia and hypocrisy

Ironically, Myanmar’s generals have always feared and disliked China. Generals Ne Win and Than Shwe, and Min Aung Hlaing himself, all displayed a deep-seated Sinophobia. During the early phase of Operation 1027, the regime even staged anti-China protests in Yangon, accusing Beijing of aiding the resistance. Min Aung Hlaing himself publicly claimed that a major foreign power was backing the offensive, clearly referring to China.

Yet, when Min Aung Hlaing’s army was struggling to combat Operation 1027, he asked for help in pressuring the resistance forces. After China complied and the military regained some ground, Min Aung Hlaing praised China as Myanmar’s “good neighbor” and “trusted friend.”

This hypocrisy defines the relationship. When convenient, the generals vilify China; when cornered, they kneel before it. In his trip to China in September, Min Aung Hlaing even claimed that China-Myanmar relations have never been closer. This is how the military leader plays the game regarding China.

China—meddlesome ‘non-interference’

China loves to lecture the world that no foreign country should interfere in Myanmar’s domestic affairs. But everyone knows how China has been involved in Myanmar affairs from the CPB era to the present day.

By claiming Myanmar’s crisis is a domestic issue while actively interfering, China has become the most meddlesome foreign player of all.

China says it wants peace in Myanmar, but remains silent while Min Aung Hlaing’s military bombs and kills civilians daily. Is this the “pauk-phaw” relationship China is applauding?

Does this “pauk-phaw” relationship, which is defined as brotherly relations characterized by familial care and loyalty, really exist between the peoples of Myanmar and China? Or is it only for dictator Min Aung Hlaing? This is a question worth asking.

But one thing is clear: Myanmar-born Chinese are in the same boat as the rest of the ethnic people in the country. They stand with ethnic Myanmar communities—except for the cronies. Whether it’s Khant Nyar Hein or Kyal Sin, two Myanmar-born Chinese youths killed by the junta during anti-coup protests in 2021, history shows that many Myanmar-born Chinese individuals have stood against dictatorship.

‘China-installed king’

In the 13th century, in the late Bagan era, Myanmar had a king called King Narathihapate. He was known as Tayoke Pyay Min, or “the king who fled the Chinese invasion”. (In fact, it was a Mongol invasion.)

Myanmar may be seeing the rise of a “China-installed king” in the 21st century.

In truth, it’s more like a “China-installed dictator” or a “dictator revived by China.” Who could this be? Another military “president” whom we can expect after the upcoming elections in Myanmar.

If China stayed out of Myanmar’s affairs, the country could shape its own destiny. But if China continues meddling, it will only prolong Myanmar’s suffering and strengthen the dictatorship.

Myanmar’s people now face two enemies: the nearest is Min Aung Hlaing’s regime and his army at home; the other are the foreign powers that support the regime with weapons, political backing and economic cooperation, particularly China.

To move forward, Myanmar’s revolution must not only defeat the junta but also neutralize China’s interference. Ethnic armed groups and the NUG must stand firm against Beijing’s pressure and stop fearing its influence.

China may believe it is playing a clever game. But in truth, it is playing with fire. Supporting the junta will only deepen anti-China sentiment among the Myanmar people—and that fire could one day burn beyond its control.

What Beijing needs to understand is that helping the hated military regime only fuels anti-China sentiment among the people of Myanmar. This could eventually lead to an uncontrollable backlash.

Another thing they must understand is that supporting the junta will bring neither stability nor sustainability. If China thinks Min Aung Hlaing’s military can rule forever, it’s making a grave mistake.

This article was originally published on The Irrawaddy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.