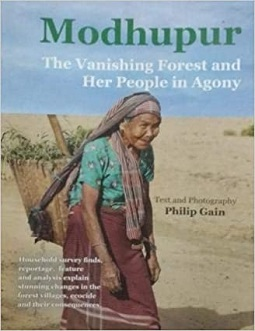

Philip Gain, Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony. Dhaka: SEHD, 2019

G. M. Shahidul Alam | 01 January 2021

Book Review

Philip Gain, Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony. Dhaka: SEHD, 2019

Philip Gain has worn, and continues to wear, several hats. A journalist by formal education, a part-time university teacher, an avid photographer, a writer, Gain is probably better known for running the Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), an NGO that works for marginalized communities, poverty and the environment. His book, Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony, appears to be the result of an honest intellectual attempt at looking at all the three issues in question based on research, analysis and suggested reforms.

Having worked in and studied their communities and their distressed localities with much attention for years, Gain has adequate understanding of the marginalized people in Bangladesh while this slender volume, enriched with photographs taken almost entirely by himself, is a valuable work on Modhupur Upazila, its inhabitants, and the demographic and accompanying changes it has been undergoing across creeping time. He is scathing in his views from the very beginning of his research report: “Modhupur can be taken as a very clear case of ‘ecocide’, or quite literally, the killing of life. As these natural forests are lost, so are the unique plants and animals, which comprise an interlaced web of life amongst various species.” He is talking about the delicate ecological balance that is being disturbed, almost always with at least some negative effects on the environment, in Modhupur, but his indictment could as well be applied to an alarming ecological situation across the world.

Gain begins with a succinct, yet quite comprehensive, account of the Modhupur Forest, the third largest forest of Bangladesh, which is located in the Tangail district. He notices a pattern of migration that impacts on the demography of a locality or a country for that matter. This part is telling of such changes: “For centuries and before the Bangalees came to live in the forest villages, this native forest patch had been home to the Garo and Koch – two ethnic communities of Bangladesh. [...] Garos are believed to be the first people of the Modhupur forest.” And so, they lived in what may be gleaned as relative peace in the deep jungle in isolation from others for close to 100 years “before the area came to the attention of the outsiders, who introduced Zamindari in the area. The Maharaj of Natore included Modhupur forest in his zamindari.” And, thereby multifarious encroachments began, albeit initially slowly, but surely, and the Garos, as well as other ethnic communities, were gradually beginning to lose much of their unique heritage.

So, and this part is relevant to the observation just recorded, “In exchange for tax payments, the zaminders or landlords, awarded forest estate and land rights to the Garo and Koch inhabitants. They secured their traditional rights to cut, burn and cultivate plots of land in exchange of taxes under the control of forest by the zaminders or rajas. Although early British colonists established the Forest Department, which brought the forests under state control,” significantly, the “first peoples of the Modhupur forest were able to maintain a peaceful coexistence with the forest undisturbed by outsiders, for many years.” However, the end of the British colonial rule ended the control of the forest by zaminders, and in 1950, the forest was brought under the Forest Department’s jurisdiction.

Since then, the Bangalees gradually outnumbered the ethnic communities. Part of the reason was demographical while the rest was due to several of the government policies that were implemented. Then the matters of demographic up-and-down accelerated, with much misfortune for the communities, their ways of life, and the state of the old forest. The forest in Tangail shrank significantly, as the governments introduced what they saw as major development efforts aimed at improving the lot of people and the forest. Gain laments that the upshot has been a part of a larger picture of plundering of the forests all over Bangladesh. So, new crops were introduced expansively, like banana, pineapple, papaya, ginger and turmeric, and sal trees, among others, benefiting primarily the non-residents.

Gain appears appalled at the human and ecological disasters, at least some of which having happened, and been happening, cannot be gainsaid: “Due to their fast-growing nature, these trees and crops have brought quick economic gains to some and have increased cash flow in the area. At the same time, they have brought many unforeseen consequences. […] Today, the land and soils are wearing thin, with no time to renew themselves between successive rounds of intensive plantation. With their traditional lives lost, many of these passive and forest-dependent people move homesteads frequently to avoid threats presented by outsiders.”

Gain has found that, which is alarming, the extensive rubber plantations in Modhupur have had profound negative impacts on the local ecology. So, the tiny patches of the remaining forestland have become sadly fragmented, leaving wildlife more vulnerable to human predation, seed banks and gene pools shrinking, and humans losing hundreds of valuable medicinal plants and medicinal compounds.

Following the displacement of sections of the indigenous Garo and Koch communities, significant cultural and social changes have affected their life and lifestyle. Gain finds: “Even the preservation of their own language has become a challenge because business transactions and schooling requirements demand a strong fluency in Bangla.” The major changes that have thus resulted are so encapsulated: “[T]hey were once able to collect important items such as food, firewood, herbs, medicinal plants, and other resources. Now they spend more money, travel longer distances, and are placed in constant danger to obtain these same items. […] These rapid changes have led many Garos to move out of the forest…to Dhaka to take menial jobs or find employment in beauty parlours.” The sad inevitability is that in many such cases, one is resigned to inevitable tradeoffs between development strategies and potential and real negative outcomes.

Gain provides a broad overview of the Modhupur forest and its people and resources. He, along with his team, carried out extensive surveys and he has presented an Executive Summary of their findings. It includes the Methodology used by SEHD, which has incorporated into the investigation, from the time it began concentrating on Modhupur forest and its people in 1993, issues of human rights abuses, anomalies associated with “social forestry” leading to massive deforestation. All of which is fine, at least as a theoretical and scholarly exercise, but the question remains how much, if at all, of its findings, reports and recommendations have succeeded in ameliorating SEHD’s focus groups’ perceived and real problems and issues. The study report was formally launched in 2019 and therefore, given the COVID-19 pandemic affecting the whole world including Bangladesh, the impacts of the study might not be known for some time.

However, the Methodology used in the survey, as well as some of the findings, should give hope for some positive outcomes regarding the specific issues related to Modhupur and the broad social and economic condition of the country. The SEHD Report does acknowledge several shortcomings related to the Survey, and when taking those into account, the Report would perhaps represent a more realistic picture of the situation in Modhupur.

Philip Gain and his team have done a yeoman’s job in carrying out the survey for the Report. It would, then, perhaps be fitting to end by quoting the Epilogue of the Report as a kind of summary of their efforts: “There is nothing more important for the people of the Modhupur forest villages to press for than for the right to land. The forest is thoroughly despoiled and most of the forestland is now turned into human habitation, plantations and crop fields. Yet the Forest Department of Bangladesh is still in control of the forest land! For tenurial rights the forest villagers have fought in the courts, appealed to the state and the Forest Department, voted politicians to public offices to speak for them and have occasionally organized resistance. The best-known resistance attempt in recent history was organized against the eco-park in 2003- 2004 that led to bloodshed and further clearing of trees. The achievement of all these efforts is little. The tenurial issues remain unsettled. Now a peaceful and (perhaps a better) option that must be explored by both local people in Modhupur and those in concerned state agencies is dialogue. This must lead to legitimization of the rights of the villagers in their current locations.” We only can hope so.

G. M. Shahidul Alam, Professor of Media and Communication at Independent University Bangladesh

This book review was originally published at https://jgsd.cgs-bd.com/