How Domestic Violence is a Threat to Economic Development

Rasmane Ouedraogo and David Stenzel | 27 November 2021

Stopping violence against women is not only a moral imperative, new evidence shows that it can help the economy.

It’s being called the “shadow pandemic”—an increase in physical, sexual and emotional abuse of women is taking place amid the lockdowns and societal turmoil caused by the global health crisis.

The evidence is only growing. In Nigeria, the number of reported cases of gender-violence linked to lockdowns increased by more than 130 percent. In Croatia, reported rapes increased by 228 percent during the first five months of 2020 compared to 2019.

The economic costs of domestic violence are higher during downturns and could make recovery more challenging.

For many women around the world, no place is more unsafe than their own homes. As the world recognizes International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, it has become clear that the pandemic has made this violence worse.

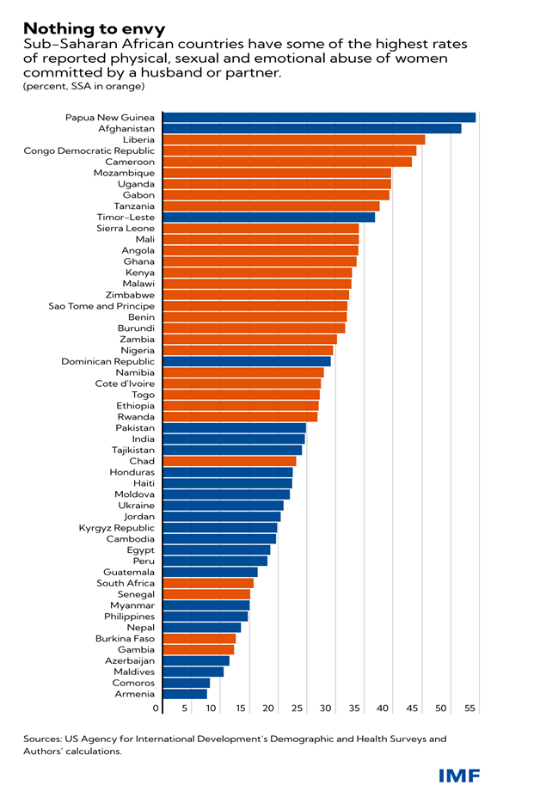

Abuse of any form is fundamentally wrong and a violation of basic human rights. New IMF staff research shows how violence against women and girls is a major threat to economic development in a region where domestic violence is widespread—sub-Saharan Africa.

The results of our study suggest that an increase in violence against women by 1 percentage point is associated with a 9 percent lower level of economic activity (proxied by nighttime lights).

A drain on society

Violence against women and girls has a multi-dimensional effect on the overall health of an economy both in the short-term and long-term.

In the short term, women from abusive homes are likely to work fewer hours and be less productive when they do work. In the long run, high levels of domestic violence can decrease the number of women in the workforce, minimize women’s acquisition of skills and education, and result in less public investment overall as more public resources are channeled to health and judicial services.

Previous studies have found domestic violence costs a given economy between 1 and 2 percent of GDP. However, these studies use simple accounting mechanisms and often don’t account for potential reverse causality.

Our research takes a new approach, matching deep survey data of women in the region with satellite imagery and employs appropriate technical methods to address endogeneity issues.

We look at data from the US Agency for International Development’s Demographic and Health Survey collected from the 1980s to the present. The surveys ask women specific questions about mistreatment.

The data come from 18 sub-Saharan African countries, covering more than 224 districts and more than 440,000 women representative of around 75 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s female population.

The surveys found that more than 30 percent of women in the region had experienced some form of domestic abuse.

To measure the impact on economic development at a district level, we compare the survey data with satellite data on nighttime lights provided by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Nightlight satellite data can be a powerful tool for measuring economic activity when the most used measure for economic activity—gross domestic product—is not available at the sub-national level.

We found that higher levels of violence against women and girls are associated with lower economic activity, driven mainly by a significant drop in female employment. The physical, psychological, and emotional violence that women experience makes it more difficult for them to achieve or maintain a job.

Based on this connection, if sub-Saharan African countries in the sample were to reduce the level of gender-based violence closer to the world average of 23 percent of women experiencing abuse, it could result in long-term GDP gains of around 30 percent.

The pandemic’s toll

An economic downturn, such as the one caused by the pandemic, can contribute to an uptick in domestic violence. This exacerbates the economic costs of domestic violence compared to normal times.

Our research also found other evidence for the negative impact of domestic violence on economic activity. Domestic violence is more detrimental to countries without protective laws against domestic violence and countries rich in natural resources where extractive industries are more likely to crowd out more women-centered jobs and lead to less economic power among females.

We also found that the economic costs of violence against women is lower in countries like South Africa, where there is a lower gender gap in education between partners and where women have more decision-making power than in other sub-Saharan African countries.

Stopping violence against women is an indisputable moral imperative, but our research shows that it’s economically important too. The economic costs of domestic violence are higher during downturns and could make recovery more challenging.

Countries should take efforts now to strengthen laws and protections against domestic violence. Strong laws are critical to deter violence against women, protect victims of domestic violence, and promote women’s participation in the workforce.

Improving education opportunities for girls is an important step in the longer term. Reducing the gender education gap gives women more economic freedom and less ability to be influenced and controlled by men.

In efforts to build back better from the pandemic, policies to support women and combat gender-based violence are more important than ever.

Rasmane Ouedraogo is Economist in the IMF’s African Department where he works on Côte d’Ivoire. Prior to joining the African Department, he worked in the IMF’s Statistics Department (Balance of Payments Division) and the World Bank’s Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice. His broad research interests relate to development economics and macroeconomics.

David Stenzel is an economist in the IMF’s African Department where he works on Senegal. Prior to joining the African Department, he worked as senior advisor to the German Executive Director and at Deutsche Bundesbank on international monetary and economic cooperation. His broad research interests relate to development, fragility, and macroeconomics. He holds a Master’s degree in Economics from Freie Universität Berlin.

This article was originally published on IMF.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.