Chinese Security Companies are Putting Boots on The Ground in Myanmar. It Could Go Disastrously Wrong

Adam Simpson | 16 December 2024

Just as the legal noose tightens on the leader of Myanmar’s military junta, with a request for an arrest warrant from the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, the Chinese government seems to be extending a hand of support.

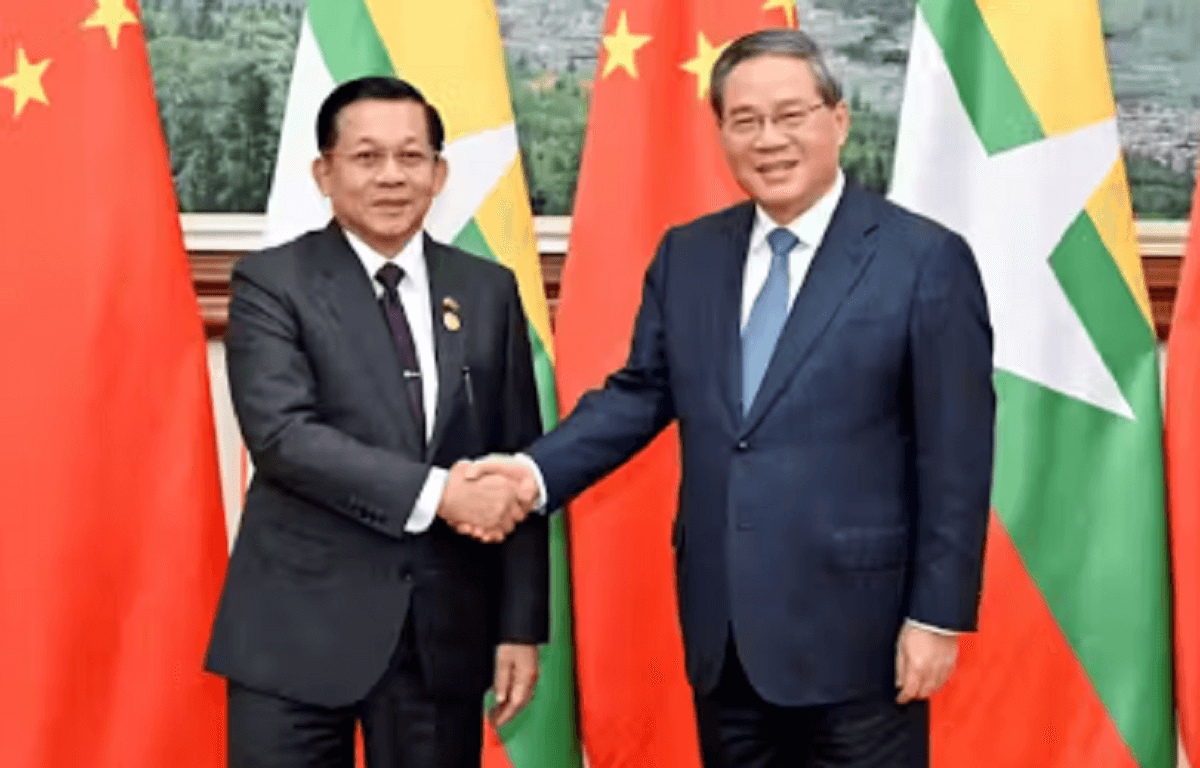

In August, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Myanmar for his first meeting with Myanmar’s junta leader, Min Aung Hlaing, since the February 2021 military coup plunged the country into civil war.

Then, last month, Min Aung Hlaing reciprocated with his first visit to China as head of the junta.

Reports in recent weeks have also indicated the Chinese government and Myanmar’s military junta are establishing a joint security company to protect Chinese projects and personnel from the civil war. This development is extremely concerning and does not bode well for any of the players involved.

The move comes after a string of significant military victories by the opposition, including the Three Brotherhood Alliance’s successful Operation 1027 over the past year. These rebel groups captured large swathes of territory near the China-Myanmar border, at least initially with China’s tacit support.

While much is still unclear about the deployment of these private Chinese security guards in Myanmar, one thing is certain: China has decided to unequivocally back the junta after years of hedging its bets.

China’s increasing use of private security corporations

Private security corporations and private military corporations are increasingly employed by a wide range of governments as a way of projecting influence and power in other countries without the diplomatic complexities that come with deploying traditional military forces.

Private security corporations provide basic security services for a country’s personnel or assets. Private military corporations, on the other hand, offer more in-depth military services for governments or other actors. This can include augmenting counterinsurgency or combat operations and military training.

China was rather late to the game of overseas private operators, but it has plenty of recent models to follow, such as Russia’s Wagner Group and the Blackwater company from the United States.

Legislative changes in China in 2009 resulted in an expansion of the private security industry, with thousands of domestic operators helping to protect private assets in China and dozens operating abroad from Central Asia to Africa.

Chinese private security corporations generally avoid combat roles and focus on safeguarding infrastructure projects, personnel and investments linked to the country’s Belt and Road Initiative.

There are reportedly already four Chinese private security corporations operating in Myanmar, but the new joint security company is likely to expand the scope and numbers of these operations.

What would they seek to protect? China’s key strategic project is the Myanmar-China Economic Corridor, which includes a proposed railway and twin oil and gas pipelines that connect Kunming in China’s Yunnan Province to Kyauk Phyu in Rakhine State on Myanmar’s western coast. China is also building a port there.

These pipelines run through territory controlled by a range of different armed groups in Shan State and Mandalay Region. The powerful Arakan Army, a member of the Three Brotherhood Alliance, also controls the area around Kyauk Phyu.

In addition, opposition groups have already seized a Chinese-owned nickel processing plant in Sagaing Region and a China-backed cement factory in Mandalay Region.

What are the possible implications?

While private security corporations are nominally separate from China’s People Liberation Army (PLA), there is little to stop the PLA from infiltrating these organisations and influencing their operations on the ground.

Having Chinese private security firms in Myanmar also creates a high likelihood of Chinese nationals being caught up in the fighting and possibly killed.

In addition, as the recent stunning fall of the Assad regime in Syria demonstrates, authoritarian regimes facing widespread militant opposition can sometimes fall quickly.

Russia and Iran are now discovering that backing a brutal regime against popular opposition can leave military and economic assets stranded when the tide turns unexpectedly. China should consider these ramifications carefully.

For Myanmar’s junta, the involvement of Chinese security forces would be an embarrassing recognition that it is unable to provide even rudimentary security for its chief ally’s economic and strategic interests.

It also makes the junta even more reliant on China than it already is. While Russia has been the main supplier of weapons since the coup, China remains a key source of military and economic engagement to the junta.

For the opposition forces, the Chinese security operations further complicate their attempts to secure control over key economic and population centres.

And it could mean China will now restrict its support for some of the ethnic armed groups fighting against the junta, such as the successors to the Communist Party of Burma, which have ethnic Chinese roots. This may force the opposition to consolidate its shift towards domestic production of small arms.

The opposition may also look to diversify its economic activity beyond smuggling or trading routes into China, potentially reducing China’s leverage over these groups in the long run.

Lastly, the Chinese security forces may further entrench anti-China sentiment throughout the country. In October, for example, the Chinese consulate in Mandalay was damaged in a bombing attack.

What are the regional implications?

India will no doubt be watching these developments with concern. If the plans go ahead, there will be increasing numbers of Chinese security forces stationed in Rakhine State, just down the road from India’s own massive investment projects in the country.

Two of Myanmar’s other neighbours – Bangladesh and Thailand – will no doubt be concerned about having Chinese forces on their doorstep and potentially sitting in on meetings with Myanmar officials.

While China’s newfound support has provided a lifeline for the junta, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will also continue to insist on a more inclusive political resolution to the conflict. They are unlikely to view increased Chinese security operations in Myanmar favourably.

Adam Simpson, Senior Lecturer, International Studies, University of South Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy