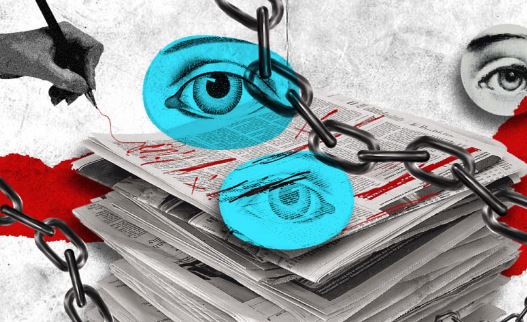

Journalism in Bangladesh is Still Fighting for Its Voice

Zillur Rahman | 13 August 2025

Following the mass uprising of 2024, many in Bangladesh thought that a fresh dawn would emerge over the nation's long-troubled media landscape. The overthrow of an oppressive regime provided a glimpse of hope for increased press freedom, accountability, and an end to years of political and legal persecution of journalists.

Instead, one year after that momentous occasion, Bangladeshi media is still under political, institutional and psychological pressure.

Over 250 cases have been brought against journalists nationwide in the last 12 months alone. While some of these examples seem to be intentional attempts to strangle critical reporting, others are the result of straightforward social media posts. There is no denying the trend: journalists who challenge authority continue to suffer significant consequences.

It may be argued that journalists can be protected from unfair prosecution and protracted harassment, either politically motivated or contrived, by the recently adopted Section 173A of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1898. The new clause allows for the discharge of an accused during investigation if a high-ranking police officer supervising the probe asks for an interim investigation report, and it reveals insufficient evidence against the accused. The question, however, remains whether this mechanism will be employed selectively or impartially.

In addition to legal consequences, the profession was recently rocked by the horrific killing of journalist Asaduzzaman Tuhin while on duty on August 7. The incident served as a sober reminder that speaking the truth can be deadly. The day before, another journalist named Anwar Hossain came under brutal attack while trying to report on extortion at a CNG-run auto-rickshaw stand in Gazipur. These instances are not unique; they are part of an increasing trend of violence and intimidation aimed at stifling the media. The profession as a whole receives a terrifying message: be quiet or suffer the repercussions.

Even the Cyber Security Ordinance (CSO), 2025, which replaced the stringent laws such as the Digital Security Act (DSA), 2018 and the Cyber Security Act (CSA), 2023, contains problematic provisions. Though the interim administration abolished some contentious sections of the DSA and CSA from the CSO, Section 42 allows the application of repressive tools previously used to harass and prosecute journalists. It states that, unless otherwise specified, provisions from the ICT Act of 2006, the Evidence Act of 1872, and the CrPC will still apply.

Similar to its predecessors, the CSO includes ambiguously worded provisions like "public confusion," "threats to national security," and "anti-state acts." Without definitions, these concepts are easy to abuse and misinterpret. Such wording has historically made it possible to carry out extensive crackdowns on civil liberties, journalism, and opposition.

Furthermore, a complicated web of corporate domination, editorial compromise, and political influence has silenced media in Bangladesh for years. Once a thriving pillar of democratic accountability, investigative journalism has virtually vanished. There is little space for journalistic independence because many prominent media outlets function at the whim of their owners' political and commercial interests.

There has not been any organised institutional reform since the government shift. The Journalists' Protection Ordinance, 2025 and the National Media Commission Ordinance, 2025, proposed by the Media Reform Commission, are two potentially promising measures that have been put on hold in bureaucratic limbo. Implementation of the "one house, one media" policy—prohibiting individuals or organisations from holding numerous media outlets—which is an admirable concept proposed by the commission, remains elusive.

Even the law that established the Bangladesh Press Council is filled with control-oriented clauses. The council risks becoming another tool of governmental supervision rather than a platform for journalist protection if its legal mandate is not entirely revised.

The structural flaws in journalist unions and media organisations are at the core of the media crisis. There are still significant political differences among many professional journalist associations, with some factions leaning towards those backing the interim government, and others towards political blocs seeking to challenge it. It is impossible to take a unified stance against challenges to press freedom because of this internal division.

Ownership of the media is another issue. It is said that political allegiance determines the allocation of new broadcast licences. Media outlets are often run to serve the vested interests of their owners, many of whom are deeply embedded in the corporate or political elite. Any departure from "approved" tales may result in regulatory harassment, licencing obstacles, or tax audits.

In newsrooms, this poisonous atmosphere often deters truthful reporting. Reporters self-censor because they fear legal issues or professional retaliation. Sensitive stories are put away. Whistleblowers choose to not hear anything. Risk assessments tend to overshadow investigative reports.

A national framework for self-regulation is desperately needed. Adopting an internal editorial code of conduct, grievance redressal mechanism, anti-harassment policy, and straightforward complaint resolution process should be mandatory for all media outlets. This needs to be true for both public accountability and internal ethics. Furthermore, a transparent, independent process should be used to handle grievance or defamation claims against media outlets made by the public, political actors, or public officials. An unbiased, non-partisan media ombudsman organisation can investigate such allegations.

In the end, media reform in Bangladesh is a matter of institutional bravery, political determination, and democratic maturity rather than merely being a legal or administrative matter. Reforms run the risk of becoming cosmetic if the top leadership is not committed. Furthermore, change will not materialise if journalists do not stand together.

Despite its challenges, this moment offers a chance to rethink media freedom in Bangladesh. But time is running short. Every delay erodes public trust, silences more journalists, and buries more truths. Bangladesh must have a free, secure, and independent press if democracy is to be more than just elections and voting booths. Our democracy will continue to be dangerously unfinished until that time.

Zillur Rahman is a journalist and the host of the current affairs talk show 'Tritiyo Matra.' He also serves as the president of the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS). His X handle is @zillur.

This article is publish on The Daily Star

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.