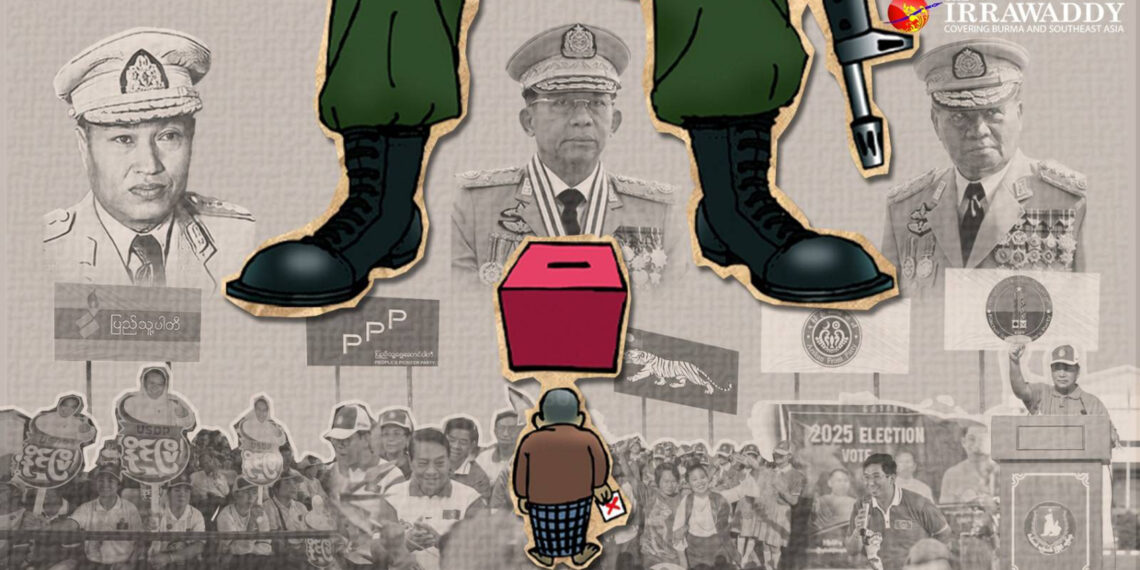

The Election — Another Political Trick by Myanmar’s Generals

Kyaw Zwa Moe | 17 December 2025

When it comes to the junta’s planned election, three groups emerge clearly in my mind: a public submerged in silence, political parties consumed by anxiety, and the military junta calmly plotting its next move. If we understand what the ruling generals are preparing, we can roughly predict what will follow the election.

But before getting to that crucial part, we must look first at why the people are “submerged”—and why the political parties are so anxious.

Submerged in silence

When I say the public is submerged, I mean they show no interest in the election and quietly oppose it. At a time when guns are pointed at them, who would dare speak freely? If they could speak without fear, they would simply say: “Why should we care? This isn’t an election—it’s a charade.”

And they have every reason to feel that way.

Myanmar’s people know elections more intimately than many outside observers. The votes they cast with hope in 1990, 2010 and 2020 were stolen or nullified—leaving behind a deep trauma. Three elections over three decades, and not a single one respected. This is why I call it “election trauma.”

So it’s no surprise that most people believe they’ll be deceived again in December and January when the junta plans to hold elections in limited constituencies. To them, what the military is staging is not an election but a political scam—an attempt to cement military power under the guise of a democratic process.

If that alone were not enough, consider this: The election is being held while the leaders they chose in 2020 remain in prison. Popular parties that oppose military dictatorship are banned. The international community’s call for an inclusive political process is being mocked openly.

The result? Everyone already knows the outcome. The Union Solidarity and Development Party—the military’s political arm—will “win.” This election was designed from the start to create a government of generals and former generals.

No one believes genuine political change will come from this. Expecting transformation from an election organized by generals who have rigged, corrupted and erased the people’s votes in past elections is nothing but fantasy. Opposition forces, revolutionary groups, and ethnic armed organizations see this election for what it is: fake, predetermined and illegitimate.

These points are easy to see—for those willing to look. But some still pretend not to see.

Anxious political parties

In contrast to the silent public, the parties entering this election are busy calculating: Who will win? How many seats they can secure? What positions might they land afterward? Their view is the opposite of the public’s. But how do they expect to win votes from an electorate that rejects the election itself?

Among the 57 parties contesting, only six are competing nationwide. Twenty-nine are ethnic parties. Most have little public support, and all are entering the race through the junta’s political roadmap—one built explicitly against the will of the people.

The six nationwide parties include the USDP led by generals, People’s Party led by U Ko Ko Gyi, People’s Pioneer Party by DawThetThetKhine, Shan and Nationalities Democratic Party led by Sai Ai Pao, Arakan Front Party led by Dr. Aye Maung and Kachin State People’s Party led by Dr. Tu Ja. These names are not new. But they are not popular either, and most are traditionally close to the regime. In truth, they function as filler parties—there to provide the appearance of political pluralism in a fundamentally undemocratic exercise.

Some party leaders hope the election will create a “new political situation” that reduces political and armed conflict. This is the realpolitik mindset: play the game the junta sets up, regardless of fairness, inclusivity or the imprisonment of opposition leaders, while largely neglecting the public’s view. Others simply seek personal gain—political survival, access to power, opportunities for wealth.

And because genuinely popular parties like the National League for Democracy and ethnic parties cannot compete, these smaller parties see an open field. Their chances of winning seats are higher. But entering the junta’s election, while the military kills people daily, is political suicide.

The scheming generals

While the people are submerged and the parties anxious, the generals are plotting with confidence. They are already assigning generals to constituencies and campaigning on social media. They are mapping out which loyalists will take which positions in parliament and government.

Of course, the mastermind is junta chief Min Aung Hlaing.

Myanmar junta chief Min Aung Hlaing

Just last month, he ordered two members of his military council—General Nyo Saw and Aung Lin Dwe—to remove their uniforms and run as USDP candidates. Ten cabinet members, including five generals, are also entering the election. These are among his trusted men, destined for top positions.

He has prepared for this moment since 2022, when he replaced USDP chair U Than Htay with loyalist U Khin Yi, a former immigration minister and police chief, and appointed Lieutenant General Myo Zaw Thein as deputy. These figures will undoubtedly appear in the next parliament and government.

Aung Lin Dwe could reportedly become Speaker of the Upper House—and therefore, under the Constitution, Speaker of the Union Parliament in the first parliamentary term. He would be the person approving the next president. In other words: Min Aung Hlaing’s enforcer inside parliament.

Other generals—like Nyo Saw and Mya Tun Oo—will likely return as ministers. Three powerful military-run ministries—Defense, Home Affairs and Border Affairs—will likely hold current positions in a new government handpicked by “President” Min Aung Hlaing.

But here is the crucial difference from 2010: Min Aung Hlaing has no intention of retiring. Unlike ex-supremo Than Shwe, he will not step aside. He intends to become president.

If he takes power in 2026, he can serve two terms—a total of 10 years—according to the Constitution. During his first term, he could even amend the Constitution (which the military itself drafted) to be able to control more of the military and government, tightening his grip on power even further. He is reportedly grooming Lieutenant General Kyaw Swar Lin to assume the powerful Commander-in-Chief position that Min Aung Hlaing holds right now. His favorite deputy, military intelligence chief Ye Win Oo, will definitely be positioned in a key role.

Min Aung Hlaing is positioning everything to ensure his own absolute control.

After the 2010 election, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was released within a week. Political prisoners were later freed under the Thein Sein-led, semi-civilian government. The NLD and other popular parties re-registered. Reforms followed.

Between then and now, however, the political situation has changed dramatically. Min Aung Hlaing is no Thein Sein, and the 2026 post-election scenario is nothing like 2010.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was 65 then; now she is 80. In 2010 she was released from house arrest and continued to live in her home freely; this time Min Aung Hlaing has ensured she does not even have a home to return to (her house has been put up for auction multiple times by his regime following a legal dispute with her brother). As for the political mandate she was granted by the people, there will be no political opening. No concessions. No reform.

Min Aung Hlaing seeks total control—nothing more, nothing less.

Kyaw Zwa Moe, Executive Editor of the Irrawaddy.

This article was originally published on The Irrawaddy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.