Education Budget Ignores the Pandemic

Manzoor Ahmed | 07 June 2021

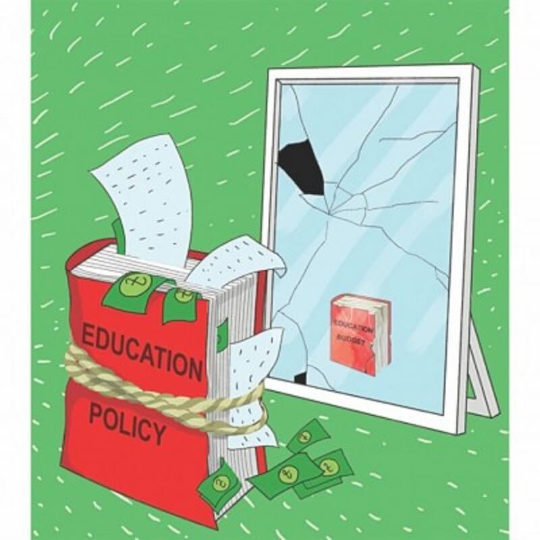

A dearth of imagination and targeted action

The education community's plea for breaking the pattern of Bangladesh having the lowest public spending on education in South Asia and among developing countries has fallen on deaf ears. A targeted response in the education budget to cope with the immediate and longer term effects of the pandemic that has kept schools closed for 15 months has also been denied.

Out of Tk 603.7 thousand crore total proposed national budget for FY21-22, Tk 72,000 crore or 11.9 percent has been allocated to education. This is lower than 12.3 percent in the revised budget for the current year FY20-21. It has been around 12 percent in recent years, though the demand from the education community has been for 20 percent of the national budget and between 4-6 percent of GDP, as recommended by UNESCO, to meet the education priorities of developing countries. The proportion of GDP share for public education has hovered around 2 percent in Bangladesh—again the lowest in South Asia and among the developing countries of the world.

The finance ministry's budget narrative cites a figure of 15.7 percent for education and technology by lumping together the education allocations with items on industry and infrastructure for information and communication technology which fall under the domain of the Ministry of Science and Technology. These activities no doubt have a contribution to make in expanding the application of technology in education. Their importance has been felt acutely during the pandemic. But one might be forgiven if lumping education and technology together is seen as a way of deflecting criticism from low education spending by presenting inflated numbers.

Arguably the more important question than that of the size of the allocation is how the education objectives, strategies and targets for the education sector are reflected in the education budget. The proposed spending has to be directed at the right priorities and the money has to be spent effectively and efficiently. On both counts, serious challenges persist.

The finance minister said in his budget speech, "During this crisis, alongside adopting life saving strategies, we will give highest priority to ensure the continuity in teaching activities by restoring normalcy in the academic environment." The operative term seems to be to return to "normalcy" and continue normal educational activities. This betrays a lack of understanding of the devastation caused to the education system by the closure of schools for 15 months.

The critical concerns have many facets—the need to re-open schools safely, protecting health and wellbeing of students and teachers while the pandemic still continues; planning and implementing a programme of restoring the prolonged learning loss; coping with mental, emotional, economic and health effects on students and teachers; and managing the implementation of a complex programme of safe re-opening and recovering the multi-faceted learning losses.

The budget speech notes "… we will implement the inclusive and science oriented education initiatives and develop infrastructure as announced in the last financial year, as well as expand the scope of our ongoing activities." It also mentions, "as many as 29,09,844 online classes have been organised… at the secondary and higher secondary level… A total of 497, 200 online classes were organised [in public and private universities]." Various independent surveys, however, reveal that the majority of students actually failed to participate in distance education because of lack of devices, problems of connectivity and the usual limitations of one-way communication in distance mode of teaching. The key lesson from this initiative clearly is that a pedagogical shift to a blended approach of face-to-face and technology-based learning is necessary, which calls for major financial investments at all levels of education.

The new education budget follows an incremental approach of continuation with expansion of the physical construction including some multi-media facilities, training of teaching personnel and an increase in enrolment, especially at the post-primary levels. The need for these planned expansions cannot be denied, but these by themselves do not constitute an immediate and longer term pandemic response. It is difficult to discern from the education budget that a pandemic still rages with devastating and multiple immediate and longer term consequences for students and the education system.

A particular concern is that the majority of the 40 million students are served by educational services not directly under government management or financially supported by the government. The proportions vary by stages, but more than half of the students in early childhood education, TVET, madrasas, and tertiary level are enrolled in institutions not financially supported by the government.

Education Watch in its recent study titled, "Bring schools and learning on track," identified key action points including financing measures. The action steps in broad terms, are four-fold: i) To reopen institutions safely with appropriate health and safety measures, each upazila and institution making coordinated plans involving health complexes and health clinics for testing, contact-tracing, isolating, and treatment as needed; ii) Within central guidelines, each upazila and institution—primary secondary and tertiary—should make their own plans involving parents, teachers, managing bodies, education NGOs and plan at least a two-year recovery programme. Elements of this plan, according to education experts, should include assessing where students are (all will not be at the same level), how they can be helped, shortening and rationalising the curricula, recasting exams, supporting teachers, and combining technology-based and classroom learning; iii) Effective implementation and management of the reopening and recovery have to involve the stakeholders beyond the education authorities and necessary financial support and incentives have to be provided; iv) the reopening and recovery plan has to be melded into a longer term education sector plan in line with the SDG4 education agenda for 2030.

While a national budget is not the instrument for spelling out a detailed educational reformation plan, it has to support the strategies for such a plan. Education experts also have suggested extending the current academic year to June next year and, opportunistically, change the school year permanently to September-June in 2022.

Most institutions at primary and secondary level suffer shortage of financial resources necessary for offering quality instruction. They will be hard-pressed to comply with the health and safety regulations and carry out the extra efforts and activities anticipated for the learning recovery programme. Additional financial support will be required from public resources for implementing the school reopening and education recovery programme inclusively for all students.

Whether the parliament members do their duty and help redirect the priorities in the budget and reverse the neglect and inaction regarding the effects of pandemic on the education sector remain to be seen. Let's hope that the parliament will take its job seriously instead of rubber-stamping the government's budget proposal.

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is professor emeritus at Brac University.

This article was originally published on The Daily Star.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.