Why Is Putin Upping the Ante in Ukraine?

Alexander Baunov | 25 September 2022

Rapidly unfolding events in Russia are effectively transforming the conflict in Ukraine from a “special operation” on someone else’s territory into a war to defend supposedly Russian land.

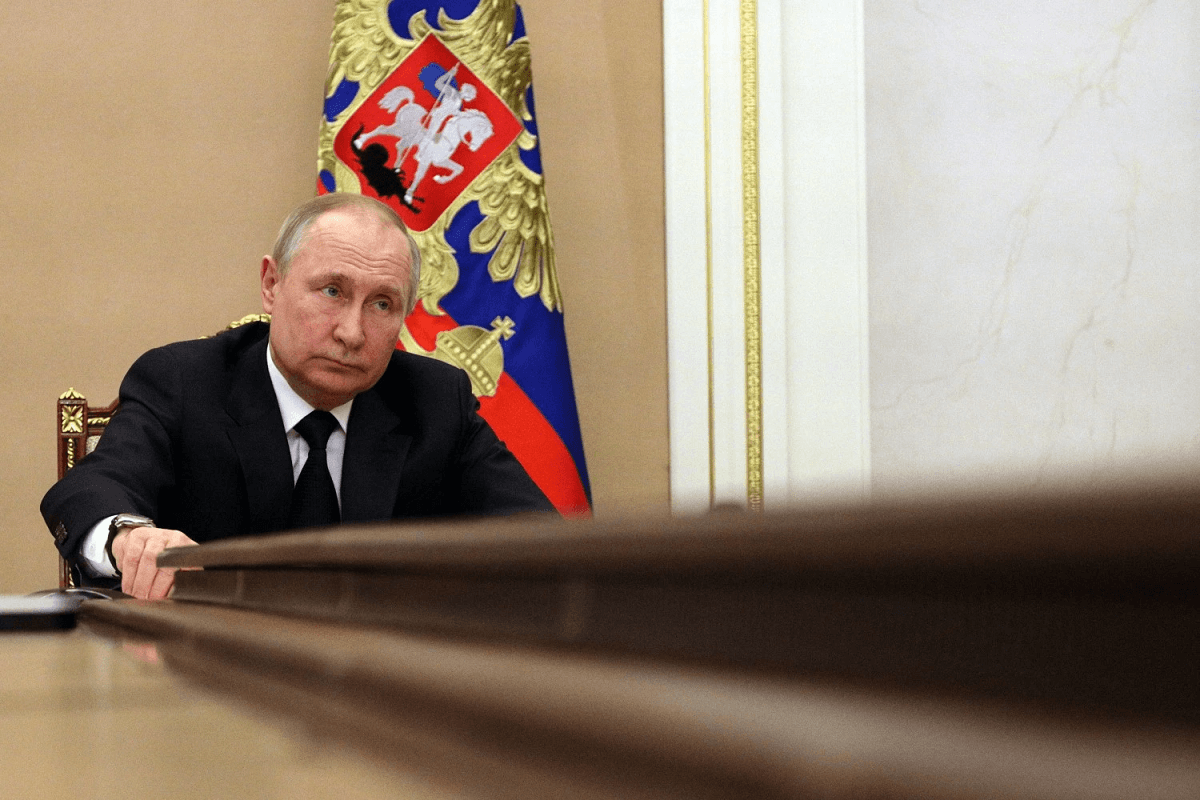

Russian President Vladimir Putin has raised the stakes in his war against Ukraine, announcing a partial mobilization on September 21, meaning 300,000 reservist troops can now be sent to fight in Ukraine.

The previous day, with no prior announcement, amendments to Russian law were introduced to the Duma and immediately passed in three readings. They stipulate harsh penalties for failing to report for military duty, surrendering, or refusing to fight.

That same day, the Russian-imposed administrations of all the regions of Ukraine currently partially or wholly occupied by Russian troops submitted requests to hold referendums on becoming part of Russia as early as the end of this week.

The message sent to the West by the combination of these three developments is: “You chose to fight us in Ukraine, now try to fight us in Russia itself, or, to be precise, what we call Russia.” The hope is that the West will balk at this.

At home, meanwhile, these events transform the conflict from a “special operation” on someone else’s territory into a fight to defend supposedly Russian land, granting the Kremlin almost unlimited rights in terms of what demands it can make of the general public.

The idea of foreign troops crossing Russia’s borders, even if the border is not where it was only yesterday, is being used by Putin to justify reconfiguring the “special operation” into a war, embarking on partial mobilization, and ramping up the threat to use nuclear weapons. In his speech on September 21, Putin said “Those who try to blackmail us with nuclear weapons should know that the prevailing winds can turn in their direction.” Russia may also now start targeting Ukrainian sites it had previously been reluctant to attack.

The truth is that time is not on Moscow’s side, and the human, material, and diplomatic resources needed for the “special operation” are running out, prompting Putin to take decisive action to try to end the war as soon as possible, cut its losses, and keep its gains. If he doesn’t succeed in ending the war, then he can at least put the blame for that on other people, and turn his invasion of a neighboring country into a defensive war, in the hope that that distinction will make the conflict more legitimate in the eyes of ordinary Russians, leaving the Kremlin free to make whatever decisions and take whatever measures it deems necessary. The problem is that Russia’s opponents do not believe that Russia has the right to any of its gains in this war.

Since the beginning of the war, there has been a divide within the Russian regime between the party of war and the party of the “special operation.” The latter party believed that only professional soldiers should be involved in the conflict, and that it should remain on the periphery of everyday life, which should largely continue as normal.

The party of war, in contrast, believes that the invasion of Ukraine should fundamentally change everything in Russia, from the economy to cultural and everyday life. This party backs a full mobilization and would like to see the confiscation of assets from the business community and an end to consumer culture in Russia.

For a long time, it seemed to the Russian leadership that the best course of action was to retain the appearance of ordinary life, and that the market economy and a consumerist society were the best guarantee of weathering sanctions. Now all of that could change.

In Putin’s logic, he was not lying when he insisted that Russia was not at war with Ukraine, and was carrying out a limited “special operation” there. For Russia has not deployed all of its troops there, has avoided carpet-bombing, and, most importantly, has largely avoided sending conscripts to fight in Ukraine.

In addition, the operation was planned to last for months, not years: officials made no secret of this, and it is entirely in keeping with Putin’s modus operandi as a former secret services officer. His ascent to the Kremlin at the end of 1999; the decimation of the TV channel NTV and Yukos oil and gas company; the choosing of a successor to Putin in 2008; his return to power in 2011–2012; the changing of the constitution to reset the clock on presidential terms; and even the Second Chechen War and annexation of Crimea were all carried out within the timeframe (up to six months) of a special operation.

Until recently, therefore, Putin was firmly in the “special military operation” camp, if not its leader. But the war has been raging for seven months, and now Ukraine is fighting back and regaining some of its lost territory. The Russian army’s chaotic retreat from Kharkiv heralded a victory for the party of war and mobilization.

Logically, that retreat could have caused plans for referendums in the occupied areas to be postponed indefinitely or abandoned altogether. After all, it’s far more shameful to lose part of one’s own country than occupied territory with undefined status. Nor can you simply abandon your own territory to go and reinforce other parts of the front, as Russia has explained its actions in Kharkiv.

The fact that the Kremlin has taken completely the opposite approach and set imminent dates for the referendums looks almost like some kind of superstitious attempt to break free from a curse. For while it is generally accepted among Russian people that their country might suffer military defeat beyond its own borders, in a people’s war on their own land, Russia will always prevail. The logic, therefore, appears to be that if the Kremlin makes the occupied land part of Russia, as it once was before, then victory is secure.

Legally redefining the occupied areas as Russian territory is unlikely to put a stop to attempts to take them back, but it will help the Kremlin to solve several tasks. Seizing entire regions of another country with the involvement of few troops requires the cooperation of a significant proportion of the local population. So far, Moscow has found enough Ukrainians (though far fewer than it was counting on when it launched its invasion) who are either pro-Russian or simply sufficiently indifferent to be able to run the occupied regions. But following the Russian retreat from Kharkiv, when collaborators were left behind, people will be more reluctant to cooperate. The referendums send a message to people in the occupied territories that Russia’s territorial intentions are serious.

Another problem has been the number of contract soldiers who have refused to fight in Ukraine on the grounds that under the terms of their contracts, they are not obliged to take part in fighting on foreign territory. Declaring the occupied Ukrainian regions part of Russia would remove those grounds.

Russian officials have always said that the goals of the “special operation” would be achieved, come what may. This was a convenient formulation, since the goals were so vague that they could be changed at any time. If it proved impossible to take all of Ukraine, Russia could limit itself to taking the country’s south and east. If that proved unfeasible, it could limit itself to the territory of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. If that couldn’t be done (as it hasn’t right now), Russia could stop at what it already has, and boost the status of its war spoils by turning them into new regions of Russia. After all, the main goal was not the prize itself, but having the opportunity and resolve to take it, thereby demonstrating that Russia was not fooling around and that it had the right to do so.

In recent weeks, this virtual achievement has been forfeited almost entirely. To try to restore it, Putin is once again raising the stakes in the hope that the other parties involved will stop where they are. If he is wrong once again, he will have to show that he wasn’t bluffing. He may resort to even more disastrous means to do so.

Alexander Baunov is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

This article was originally published on Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.